Published On March 28, 2022

As someone who manages 13 chronic and recurring conditions, including diabetes and kidney disease, Claire Sachs relies on a fleet of providers to help her make choices about treatment. “Literally to survive, I have to put my trust in a lot of people,” says Sachs, who works as a patient advocate in Maryland. Since childhood, she has been in and out of physicians’ offices and hospitals, and occasionally a misdiagnosis or unsuccessful therapy has tested her faith in the health care system. Through the years she has fine-tuned where to place her trust, in part based on practitioners’ credentials and expertise, but also on a feeling of security and transparency when she’s in their office. She understands that this quality is hard to put into words, and even harder to generalize beyond her own experience. “What one person needs and expects from a physician to build trust may be very different from what someone else is looking for,” she says.

Yet however trust is defined, it is essential to the practice of medicine. Trust is the foundation of the physician-patient relationship, and a high level of trust has been shown to lead to improved experiences for patients and better compliance and outcomes. In the larger context of health care, a measure of trust is required in relationships throughout the system—between clinicians and their employers, between health officials and the public, between insurers and hospitals. That variable web of trust is crucial, if difficult, to measure and track, says Lauren Taylor, assistant professor at NYU Langone Health. “Trust is powerful,” Taylor says. “When it’s there, you can move ahead, often with better results—because everyone is on board. But when trust is absent, everything grinds to a halt.”

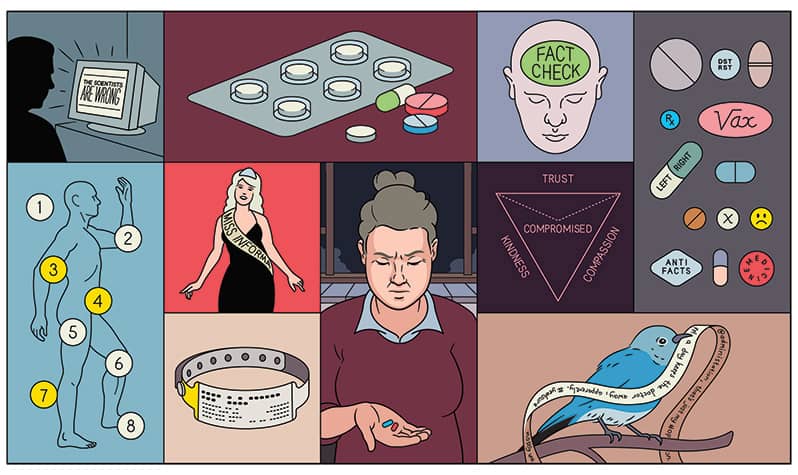

Increasingly, that trust is waning. The proportion of people who express “quite a lot” to “a great deal” of confidence in the medical system slid from 73% in 1966 to 44% in 2021. People of color, those younger than 50 and those with less education and lower incomes all have lower-than-average levels of trust in health care. And in terms of being trusted by its citizens, the U.S. health care system fares worse than many others, ranking 19th in a 2021 global ranking, far below developing countries such as India, Thailand and Nigeria.

As it drags on, the COVID-19 pandemic continues to shake trust in health care, and it comes at a time of declining confidence in government, business, organized religion, higher education and the news media. “The collapse in trust has an epidemic quality to it,” says Robert Blendon, emeritus professor at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, who has researched the topic for decades.

A lack of trust during the pandemic has almost certainly worsened consequences. As of January 2022, the United States ranked 59th in the global vaccination race, lagging behind many nations with higher trust in their health care systems, and distrust has also fueled rebellion against masking and other measures to limit the spread of COVID-19. That harm will outlast the pandemic, both for public health and individual patients, says physician Richard J. Baron, president and CEO of the American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM)—which certifies one in four doctors in the United States—and the ABIM Foundation, a nonprofit established in 1989 to advance medical professionalism and improve health care. “Looking ahead, distrust will continue to undermine how patients receive and relate to medical recommendations of all kinds,” he says.

This creates an urgency not only to define trust but to implement solutions that could help rebuild and sustain it, says Baron. “There’s an opportunity for health institutions to make trust-building a core priority, a cornerstone of better health,” he says.

Today’s worries about trust would have seemed novel during most of the early history of medicine. Patients weren’t asked to trust their physicians; rather, they were instructed to do so. The Original Code of Medical Ethics, issued by the American Medical Association in 1847, required patients’ “obedience” to their physicians’ recommendations. But in 1925, in a lecture to students at Harvard Medical School later published as an essay, “The Care of the Patient,” Francis Weld Peabody called for a relationship built on reciprocal trust. “The care of a patient must be completely personal,” said the Boston physician, and this could occur only if patients opened up to their physicians about all of the concerns and ailments they had, a deeper personal knowledge that would lead to the best care options.

Peabody’s essay remains on many medical schools’ curricula, and for decades after it was published, medicine was dominated by the kind of personal, trusting relationships between doctors and patients that he described. Solo practitioners made house calls, and “if you asked average Americans in 1950 whether they trusted the health care system, their answer would likely have been, ‘what system?’ ” Taylor says.

But public confidence in medicine peaked in the mid-1960s. The decline afterward may be surprising, considering how much medical progress was made. Yet other kinds of “progress” have been less welcome, says Blendon. Hospitals grew and consolidated into health systems and insurance companies further inserted themselves into the physician-patient relationship. Increasingly forced to interact with people they didn’t know, many patients came to feel anonymous and vulnerable, Taylor says.

At the same time, medical practitioners have found themselves working in increasingly impersonal systems that require them to move patients in and out of the office briskly, leaving them little time to establish meaningful rapport. Indeed, lack of time with their doctors is a chief complaint of patients who say they don’t trust them. Those patients’ attitude is, “I won’t trust your knowledge until I know you care,” says Daniel Wolfson, executive vice president of the ABIM Foundation.

Two reports by the Institute of Medicine—“To Err is Human,” released in 1999, which explored medical errors and patient safety, and “Crossing the Quality Chasm,” in 2001, which called for higher-quality care—also contributed to public mistrust of the profession. While the reports had a positive impact on the practice of medicine, highlighting needed changes and pointing out mistakes, they shattered illusions about the infallibility of health care. Some patients, reading about the reports in their newspapers, began to feel that there were cracks in the system.

A third of people said their trust in the health care system decreased during the pandemic.

The pandemic has introduced an entirely new phase of uncertainty. In a recent survey, about a third of people said their trust in the health care system decreased during the pandemic, compared with only about one in 10 whose trust grew stronger. One population with continued distrust is those who have traditionally lacked equal access to health care. Those in underrepresented groups often have a history of discrimination from providers and many have suffered a disproportionate number of COVID-19 deaths. One recent survey found that Black respondents were twice as likely as whites to say they have experienced discrimination in a health care facility—and those who had been discriminated against were twice as likely as others to say they don’t trust the system.

Others who have lost trust fall on the far ends of the political spectrum. As journalistic and institutional trust among these groups has faltered, “truth decay” sets in, in which the value of medical facts is increasingly discounted. With the proliferation of misinformation online and in social media, many Americans now have trouble distinguishing fake news from factual accounts, and an unceasing torrent of medical misinformation has contributed to suspicion of physicians and their guidance.

Attacks from politicians have further undermined trust in public health officials. One particularly vexing charge is that these officials sometimes change their recommendations about COVID-19 preventive measures, which detractors say sows doubts about their truthfulness and the value of their advice. Almost half of Americans in a recent survey said they don’t trust the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and even fewer trusted their state health departments. That poor relationship has added suspicion around their guidelines for vaccines, mask wearing and business restrictions.

Members of the public aren’t the only ones losing trust in the system. Almost a third of physicians, stretched thin by dealing with wave after wave of the pandemic and beset by shortages in protective gear and other challenges, said in a recent survey that their trust in the health care system and their organizations’ leadership had decreased; 43% said they trusted government health agencies less than they did before COVID-19. “Particularly at the beginning of the pandemic, the news changed every day about what we should do in terms of protecting ourselves and our patients and treating this disease,” says Jarrett Weinberger, who practices at Detroit Medical Center and is an associate professor at Wayne State School of Medicine.

At the same time, however, some physicians have said they now trust each other more than they did before the pandemic. “There’s a sense, by now, that we’re all in this together and we need to support each other,” Weinberger says.

Against this backdrop of declining trust and its consequences, there’s an urgency for researchers to learn what can be done to rebuild it, says NYU’s Taylor, who recently coauthored a study that analyzed more than 750 papers on trust published during the past 50 years. She says that finding consensus about how to measure trust is challenging, as is the road to practices that might help increase it.

Stimulating more research is one objective of the Building Trust initiative, a national campaign that the ABIM Foundation launched in 2018. Several dozen collaborators, including hospitals and health care systems, specialty societies, health plans and consumer organizations, have signed on to explore how to elevate trust while also looking at the related goals of reducing systemic racism in health care and addressing medical misinformation.

As part of that effort, the foundation issued a Trust Practice Challenge, which invited organizations to submit approaches they’ve used to help build or rebuild trust. One entry featured long-standing efforts at Massachusetts General Hospital to build trust through shared decision-making. Providing decision aids to patients improves their knowledge, reduces conflicts about care decisions and helps patients clarify what they want from their treatment, says Karen Sepucha, director of the Health Decision Sciences Center at MGH and an associate professor at Harvard Medical School.

Shared decision-making can be particularly critical in building trust with patients considering surgery, Sepucha says, and in a recent study, she and her colleagues tested decision aids that provided information about the benefits and risks of surgical interventions for osteoarthritis of the hip and knee, herniated discs and spinal stenosis. Armed with accurate information about their choices, patients were better able to share their views with their surgeons. “It’s not about persuading patients to adopt one treatment over another,” Sepucha says. “Decision aids help patients guide us as much as we’re guiding them.” After the decision aids were implemented, patients reported better communication with their doctors and a higher level of trust.

Another winning submission to the Trust Practice Challenge is a case study about UnityPoint Health Prairie Parkway LGBTQ Clinic in Iowa. Kyle Christiason, a family practice physician, helped found the clinic nearly five years ago after his eldest child, then a preteen, came out as a transgender boy. Finding culturally competent care for their child required a four-hour drive from their rural town. “The origin of our clinic started with a recognition that it was absurd to have to travel that far just to get the care our child needed,” says Christiason.

The LGBTQ community has long experienced discrimination and other health barriers, putting people at heightened risk for mental health problems such as depression, addiction and risk for suicide. In addition, patients are less likely to access preventive care, such as cancer screenings. “The trust crisis here is particularly pronounced, with about one in five physicians declining to provide care to transgender patients,” Christiason says, though often less because of bias than a lack of training. “My suspicion is many physicians don’t feel equipped,” he says.

Shared decisions can be critical in building trust.

Christiason approached his employer, and in 2018, UnityPoint designated two nights a month to provide primary care and some specialty care for LGBTQ patients. Some changes, such as asking for patients’ chosen names and for their pronouns, were designed to build trust by letting patients know this was a place that understood their concerns. Clinicians also became fluent in addressing treatment issues affecting this patient population. The organization also provided additional training for staff.

Today, the clinic provides care to 300 patients, double its initial roster, and UnityPoint has opened a second LGBTQ clinic in Des Moines. “This approach is not only a replicable model for LGBTQ care, but also a framework for clinical care for any marginalized and vulnerable population,” Christiason says. “What sets it apart is the depth of thought and consideration given to every interaction, decision and connection.” It has built trust in patients whose previous experiences with the medical system often left them feeling wary and excluded.

In Dallas, other methods were used to foster trust in a community that had long been underserved. “To build trust you have to move beyond the walls of the hospital,” says Fred Cerise, a physician who serves as president of Parkland Health and Hospital System in Dallas, one of the largest public hospital systems in the country. “We asked people in our community to reflect on what we can do better,” he says, a process that has led to numerous substantive changes.

One initiative that came out of that effort is RIGHT Care, through which Parkland behavioral social workers work with rapid-response teams from the fire department and police to help patients experiencing behavioral health emergencies. The program, in its fourth year, now diverts about a third of such encounters away from busy emergency rooms and jails. A paramedic, police officer and social worker are all part of a team that responds to 911 calls identified as a mental health crisis. Teams are assisted by a mental health clinician in the 911 call center. Together the team focuses on how to handle behavioral health situations, stabilize patients on the scene and connect them with community agencies that provide social health services and medical attention.

These experiments show several approaches that could help rebuild trust in medicine, and others are sure to emerge. Yet they come at a time when cheers for the “health care heroes” of the pandemic have, in many cases, given way to virulent attacks on medicine and its practitioners. Medical misinformation has become an online industry, and at least half of U.S. states have adopted laws making it harder for state and local agencies to protect public health. Trust, it seems, may become another casualty of the pandemic, and the implications are far reaching, says Adriane Casalotti, chief of public and government affairs for the National Association of County and City Health Officials, which represents nearly 3,000 local health departments across the country. Local health officials are a first line in offering the public factual, life-saving information, “and if they are not allowed to do their job and give correct science information because of an anti-science political agenda, the outcome will be that people get sick and may die,” Casalotti says.

“There is no single magic bullet that can cure the problem of misinformation and everything that comes with it,” says Adam Berinsky, Mitsui professor of political science at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. But there are incremental solutions that can make a difference, he says. Even if patients don’t know what to believe, and don’t trust the health care system, most still trust their own physicians. “So that’s the person who needs to be delivering the information,” Berinsky says. “If we can rebuild trust physician by physician, and reach some people some of the time, it can lead to better outcomes.”

Restoring trust in public institutions, their leaders and in science and medicine overall is going to be a long, difficult process, says Blendon. Yet as the country emerges from the pandemic, it might adopt an approach used after 9/11 to get at the truth of what happened and reassure the public that steps are being taken so that it can’t happen again. Blendon and others envision establishing bipartisan commissions at the federal, state and local levels to examine how public agencies lost credibility with the public. “We need to step back and make sure that in the future, these issues are not polarized by partisan politics ever again,” he says.

Dossier

BuildingTrust.org, ABIM Foundation. The online clearinghouse for the Building Trust project has case studies, videos, opportunities to network and updates on progress.

“A Trust Initiative in Health Care: Why and Why Now?” by Timothy Lynch et al., Academic Medicine, April 2019. The authors describe the importance of trust in health care, examine reasons for the decline, including larger societal trends and others specific to health care and the need for champions.

“The Future of Health Policy in a Partisan United States,” by Robert Blendon et al., Journal of the American Medical Association, April 2021. The paper explores profound political divisions on key issues of health care policy—COVID-19, universal coverage and national health insurance reform, U.S. health care system reform, and race and disparities in health care—and their implications for the future.

Stay on the frontiers of medicine