Published On November 20, 2021

In June 2020, Kristin Urquiza’s father caught the COVID-19 virus. Two weeks later, the 65-year-old was dead. Like so many others bereaved by COVID-19, Urquiza didn’t get a chance to say goodbye or to hold a funeral with loved ones. It seemed as though her dad had just vanished. In the aftermath of his death, she rode rolling waves of rage that alternated with profound sorrow. “I couldn’t live with it,” she says. She needed to break the cycle of her grief, but didn’t know how.

Many people in her father’s neighborhood—a predominantly Latino area of south Phoenix—were also suffering. Citywide, infections had surged 151% over the first half of June, which was just after the city’s stay-at-home order expired in May and before a June 15 mask mandate. His neighborhood had notched some of the highest case counts, in part because many of the residents worked front-line jobs at hospitals, restaurants, grocery stores and other essential businesses, putting them at high risk. Many households struggled financially—Urquiza’s father had just been laid off from his manufacturing job—and those who died often left their loved ones in a precarious economic place.

Urquiza began to worry about the next wave of victims: the bereaved and grieving. Many of them would face tragedy without even her modest resources, which had allowed her to see a psychiatrist and pay for antidepressants and anti-anxiety medication. To help herself and others lost in grief, she drew on her experience in social and environmental justice advocacy to create a national organization called Marked by COVID. The nonprofit offers online support groups, engages in political advocacy and sponsors regional and national memorials for those who lost loved ones to the pandemic. Connecting with other people in similar circumstances, she says, helped her get through the most acute stages of her pain.

A national body of mourners has taken shape in the wake of COVID-19. They grieve not only the more than 700,000 U.S. deaths brought by the virus but also hundreds of thousands who have died from related causes: missed physician visits and canceled procedures caused by overcrowded hospitals or fears of catching the virus, and a spike in substance-misuse deaths provoked by the pandemic’s economic and emotional stresses. If every death affects between two and 10 people, as research estimates, the global count of pandemic mourners may lie somewhere between 8 million people—roughly the population of New York City—and 40 million people, the population of California.

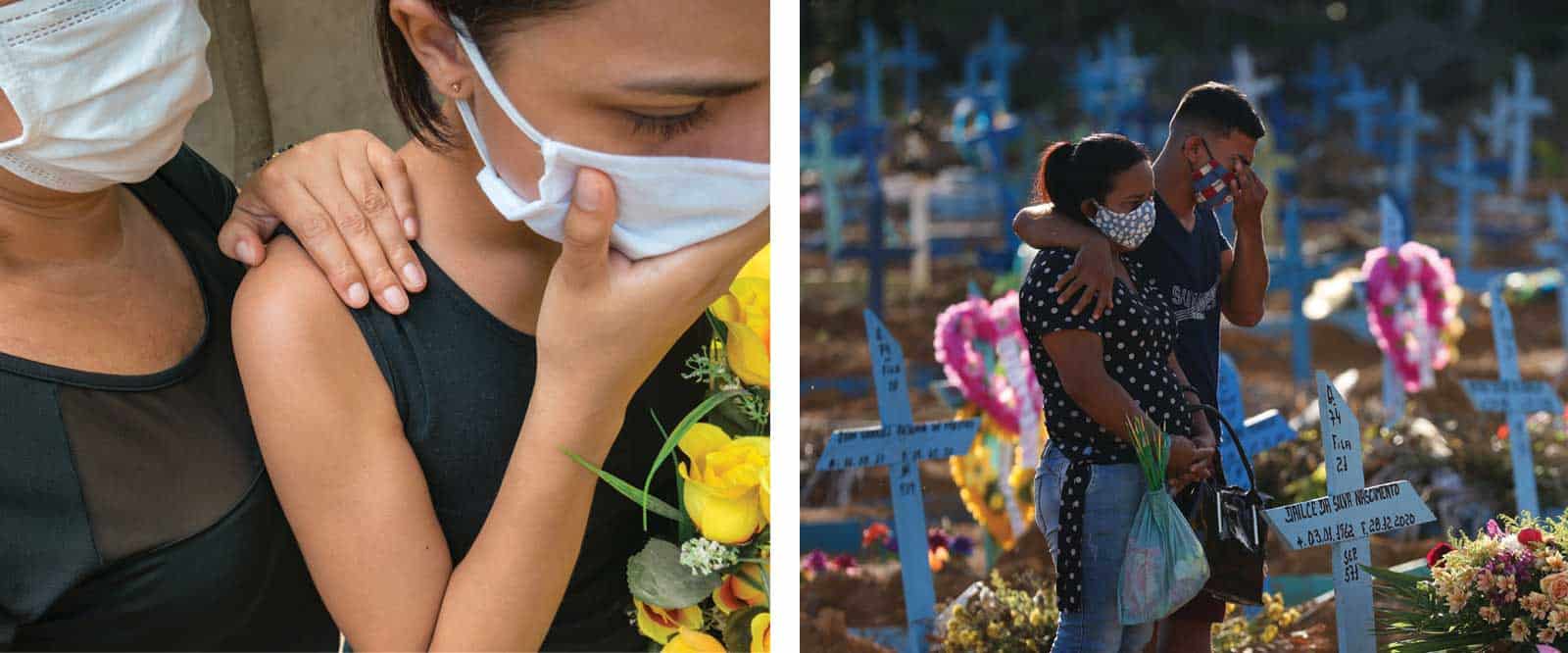

Above Left: Hector Pertuz/Getty Images; Above Right: Photo by Michael DANTAS/AFP/Getty Images

LEFT: A funeral service in New Rochelle, New York, for Conrad Coleman Jr., a 39-year-old who died from COVID-19 just two months after his father also died from the virus. RIGHT: Relatives wait to receive the body of a loved one at a mortuary in New Delhi.

Grief is a natural waypoint in life. The experience of it is “as individual as our lives,” wrote the late Elisabeth Kübler-Ross, author of the landmark On Death and Dying, which introduced her popular five-stage model of grieving. But while some grief is natural and even valuable, when extreme or disordered, the emotion brings a biological toll. Of special concern to psychiatrists is prolonged grief disorder (PGD), a condition added only last year to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, or DSM-V. PGD is defined as almost daily yearning for a deceased loved one, a condition that causes long-term, clinically significant distress or impairment that can lead to suicidal behavior and correlates with early mortality and increased rates of heart disease and cancer.

Under normal circumstances, 10% to 15% of bereaved people are thought to develop PGD. But pandemic-era deaths were largely unexpected and sudden, often coupled with financial woes and experienced without the normal channels of social support. All three of those factors are associated with a higher risk of PGD and may have doubled or tripled its prevalence, some researchers estimate.

The consequences could be especially grave in BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, people of color) communities, which have experienced some of the pandemic’s greatest losses. An August 2020 survey found that 39% of Black Americans and 31% of Hispanic Americans knew someone who had died from the virus, compared with only 18% of white Americans. These communities also experienced greater pandemic-related job losses, were already underserved by mental health services and suffer from other systemic health inequities.

“People of color, but especially African-Americans, have such a long history of brutal loss,” says Katherine Shear, a psychiatrist at the Columbia University School of Social Work and founding director of the Center for Complicated Grief. “Those traumas get transmitted across generations, and in combination with ongoing, current racism and disparities—this is hugely impactful in how deeply someone is going to experience a COVID death,” she says.

On Nov. 28, 1942, the Cocoanut Grove Fire tore through a nightclub in Boston, killing 498 people. The deadliest nightclub fire in history, it became the subject of the first-ever systematic study of the physical and psychological features of grief. Erich Lindemann, a German-American psychiatrist, collected extensive data from bereaved family members. Two years later, he published “Symptomatology and Management of Acute Grief,” a paper that established many of today’s standards of psychological care after disasters. Lindemann, who later became chief of psychiatry at Massachusetts General Hospital, found that acute grief often caused hostility, guilt, and a loss of social habits. He had seen similar reactions in patients who’d had organs removed, and he concluded that losing a human relationship was similar to losing a part of oneself.

Although research on grief advanced significantly over the next half century, few psychiatrists treated it as a distinct medical condition, says Holly Prigerson, a professor of geriatrics at Weill Cornell Medicine and co-director of the Weill Cornell Medicine Center for Research on End-of-Life Care. In the 1990s, when Prigerson began to study bereavement, any pathology that arose from grief was characterized as depression. But Prigerson’s studies led her to identify a collection of symptoms associated with mourning that were distinct from depression and often had specific medical consequences. In 2009, Prigerson and her colleagues published results of the Yale Bereavement Study and presented a comprehensive proposal for a new diagnostic entity: prolonged grief disorder.

Above Left: Photo by John Moore/Getty Images; Above Right; Photo by Prakash SINGH/AFP/Getty Images

LEFT: funeral service in New Rochelle, New York, for Conrad Coleman Jr., a 39-year-old who died from COVID-19 just two months after his father also died from the virus. RIGHT: Relatives wait to receive the body of a loved one at a mortuary in New Delhi.

PGD is described as an experience of prolonged yearning and numbness, a state that can give rise to mistrust, bitterness or a feeling that life is meaningless. Some people with PGD have confusion about their identity after the loss, or may avoid confronting the reality of it. All find it difficult to move on with life. Prigerson and her colleagues also found that PGD, as proposed, was distinct from other mental disorders—major depressive disorder, generalized anxiety disorder and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)—and its victims had an increased risk of future psychiatric diagnoses, suicidal ideation, functional disability and low quality of life.

PGD has distinguishing genetic and biological characteristics. Those who suffer PGD appear to have distinct patterns of expression in immune system genes—specifically, in the type I interferon pathway, which governs immunity against some viruses, bacteria and other invaders. In bereavement, people with PGD also appear to have higher levels of inflammatory biomarkers, such as IL-1RA and IL-6, circulating in the blood as well as patterns of cortisol dysregulation that are consistent with chronic stress.

The global count of pandemic mourners may lie somewhere between 8 million people … and 40

million people.

Like many psychiatric conditions, the causes and severity of PGD extend beyond biology to life circumstances and even cultural elements. “This kind of suffering owes something both to nature and nurture,” says Prigerson. She offers the parallel of someone who has a genetic vulnerability to alcoholism, but who may only become addicted if she is exposed to certain life stressors and lives wihtin a culture that condones alcohol consumption. While the diagnostic criteria for spotting PGD are straightforward—debilitating grief that lasts a year or more, or more than six months for children and adolescents—the causes are complex, as is the question of effective treatment.

Helping those who are lost in mourning may be bound up in a more fundamental question: What is profound grief? Comparing it to other known brain phenomena, research from the past decade suggests that PGD may share the greatest similarities with addiction. For a 2008 paper, Mary-Frances O’Connor, a psychiatrist who directs the Grief, Loss and Social Stress (GLASS) Lab at the University of Arizona, worked with women suffering from prolonged, unabated grief. In the laboratory, they were hooked up to fMRI brain scans and triggered with stimuli related to the deceased. The scans showed activity in the brain’s nucleus accumbens region, in neural reward pathways that are active in addiction. Those experiencing routine and shorter-lived periods of grief showed activity only in the pain centers of the brain.

“It was a novel idea—that yearning for a deceased loved one is the same as craving,” says Eric Bui, a psychiatrist at the Center for Anxiety and Traumatic Stress Studies and Complicated Grief at Massachusetts General Hospital and president of the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies. More recent studies have provided further evidence of a link between PGD and a number of reward-related regions of the brain, as well as to altered signaling of oxytocin, a hormone involved in social bonding and attachment.

These findings have led a few researchers to consider treating PGD with medications designed for depression and addiction. Antidepressants haven’t been effective in clinical trials, but there is some hope for naltrexone, a medication often successfully used to treat alcohol and gambling addictions. Earlier this year, Prigerson launched a clinical trial that will be the first to study naltrexone for PGD. Naltrexone blocks opioid receptors in the brain, inhibiting the release of dopamine, which in turn inhibits the reward pathway. Prigerson is hoping that naltrexone will stop the “reward” triggered by a loved one’s memory. That could, in turn, free someone from the most severe symptoms of the condition and allow that person to adjust to a new reality.

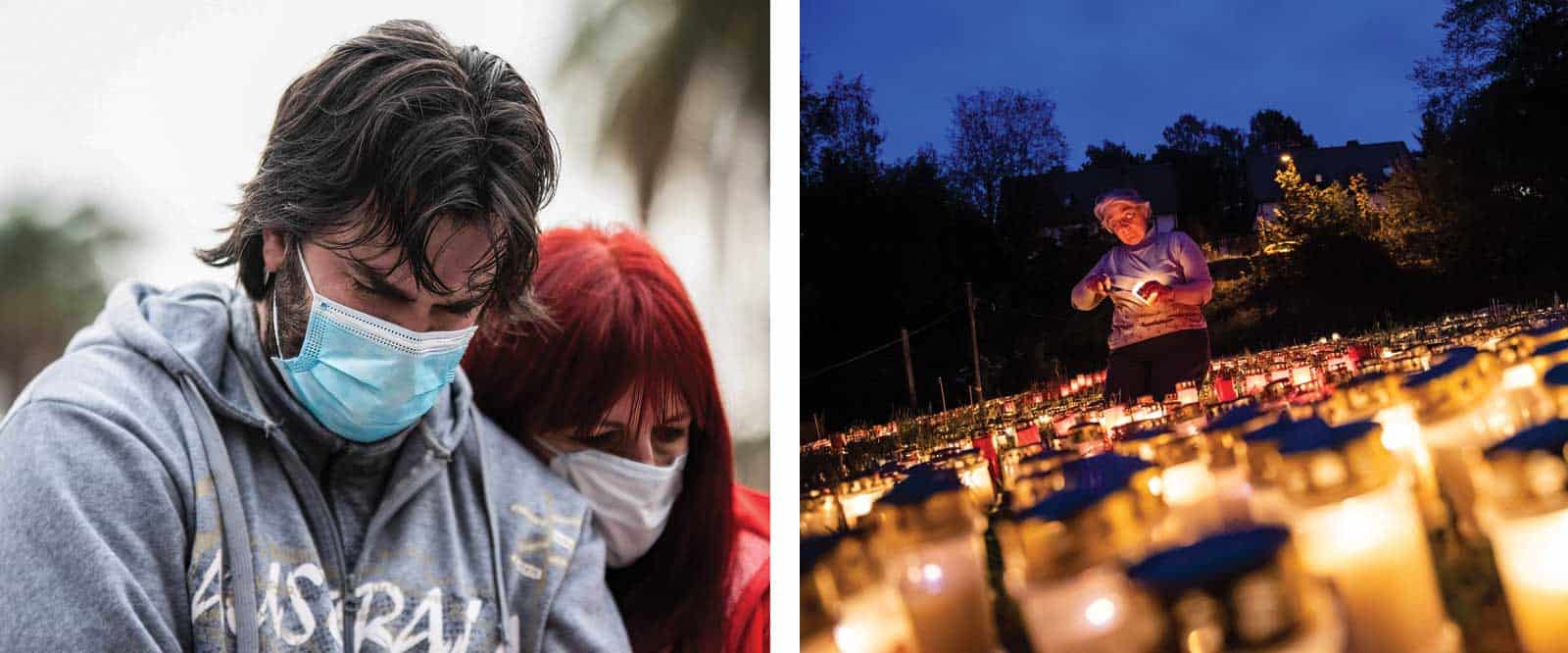

Above Left: (Photo by Manuel Cortina / SOPA Images/Sipa USA)(Sipa via AP Images); Above Right (Photo by JENS SCHLUETER / AFP) (Photo by JENS SCHLUETER/AFP via Getty Images)

LEFT: A couple cries after leaving a stone for a COVID-19 victim at the “March of the Stones” tribute in Buenos Aires, Argentina. RIGHT: Gertrud Schop lights candles in Zella-Mehlis, eastern Germany, for each of the more than 8,000 COVID-19-victims.

So far, though, only a handful of psychotherapeutic treatments have proved to be effective, including cognitive behavioral therapy and exposure therapy. The most effective is a 16-week course of weekly one-on-one psychotherapy, a protocol developed and validated by Columbia’s Katherine Shear. Her complicated grief therapy—also known as prolonged grief disorder therapy (PGDT)—has more in common with PTSD treatment than with therapies for depression or addiction. She does, however, include a module called “motivational interviewing,” which has been successful in addiction treatment.

The PGDT therapist helps bereaved patients through seven “healing milestones” that enable them to understand the grief and their own emotional responses, strengthen their current relationships and help them find new ways to live with reminders and memories of the person who died. “We help people revise the mental representation of their deceased significant other so that the representation can still provide support and comfort,” says Shear. “That requires accepting the reality that the person is gone and not coming back.” In clinical trials, this approach has been shown to help resolve the symptoms of disordered grief in 70% of cases among older adults and 50% in the general population.

So far, the only treatment proved to be effective is a 16-week course of weekly one-on-one psychotherapy.

But talk therapy is expensive and time-intensive, and it relies on a mental health care network that is already overstrained. Some researchers are now looking at ways to make Shear’s CGT model more accessible. For instance, Naomi Simon, a professor of psychiatry at NYU Grossman School of Medicine and director of the division of Anxiety and Complicated Grief Disorders, is developing a “step care” approach. Therapists would start with group-based psychoeducation and mind-body approaches and only “step up” to individual psychotherapy for those who really needed it. And Eric Bui has submitted grant proposals for novel uses of artificial intelligence—using data to predict which mourners might need extra help in moving on.

As efforts to amend PGDT suggest, delivering real help to those who need it can be tricky—particularly in communities of color, which have suffered the greatest losses. Beyond the expense and time required to deliver such therapies, few clinicians have training in grief support, and there are no graduate programs in grief and bereavement, says Robert Neimeyer, a psychology professor at the University of Memphis and director of the Portland Institute for Loss and Transition, which offers training and certification in grief therapy.

Grief support often falls to hospice workers, who are required to provide this kind of care to bereaved family members for up to a year in order to receive Medicare reimbursement, says Amy Tucci, head of the Hospice Foundation of America. Yet Medicare offers few guidelines about what such care should entail, and hospice workers get little or no training in grief support. Proposed national mental health legislation would change that, providing more funding for grief training, grief support staffing and grief services.

Above LEft: Photographer: Nathalia Angarita/Bloomberg via Getty Images; Photo by MICHAL CIZEK/AFP via Getty Images

LEFT: A mourner at the Paramo de Guerrero nature preserve near Cogua, Colombia, where trees are planted with the ashes of COVID-19 victims. RIGHT: A woman at the Old Town Square in Prague, where thousands of crosses have been drawn as a tribute to victims.

In the meantime, already overstretched community organizations have been doing their best to get support to the bereaved quickly. One of those, in the Harlem neighborhood of New York City, is the Hope Center, a mental health treatment facility that is connected to a Baptist church, a liaison meant to help overcome the stigma against mental health care in the Black community. Early in the pandemic, the center’s wait-list doubled for free grief therapy services, which are modeled after Katherine Shear’s treatment program at the Center for Complicated Grief and provided by licensed clinicians, says Lena Greene, the center’s executive director. The Hope Center enlists its pastors and other staff to conduct assessments to identify those who might need further mental health treatment.

To reach those who don’t have access to one-on-one services or who aren’t ready for that kind of counseling, the Hope Center also offers support groups and group events. Shear has given talks—“healing conversations”—about grief and this fall, the center planned to host a conference on mental health, spirituality, racism, grief and loss. To get a better sense of the problem in the Harlem community—and a better understanding of how grief interacts with racism and trauma—the center will roll out a survey in early 2022.

“The majority of the people we see are African American,” says Greene. “They have been dealing with these historical traumas, so we make sure that our therapists are addressing systematic injustices and talking about the impact of racism on people’s ability to cope on a daily basis.” Greene is also working with a team of pastors to help a Missouri church replicate the Hope Center model.

Harlem has the Hope Center, but many other underserved communities are still desperately short on grief support. Online groups fill some of the gaps, but can’t substitute of in-person counseling. Chris Kocher launched and ran the nation’s largest network for gun violence survivors and the families of shooting victims, and when the pandemic began, he created the online COVID Grief Network. In asking local communities what they needed, Kocher found that although online peer support was appreciated, many people also wanted local, physical spaces and in-person access to mental health professionals who would show up week after week.

Leaders of COVID-19 support groups are hoping for help from the Biden administration and wrote a letter in February 2021 urging the president to allocate funds to grief support, including grief training for the public and for social workers, psychologists, teachers and clergy. So far, though, the only two measures taken on the federal level have been a new federal bereavement leave policy and reimbursement of up to $9,000 in funeral expenses for those who died of COVID-19. That leaves most of the grief response to local volunteers, many of whom are running out of steam. And as the one-year anniversaries of more U.S. COVID-19 deaths arrive, more cases of prolonged grief will rise to the surface.

“We have to address the monumental pandemic of grief and trauma that we’re living through,” says Kristin Urquiza, whose father’s death is still fresh in her memory. “So far, mutual aid community groups like Marked by COVID have been leaning on one another and doing our best. We’ve pulled together to funnel the generosity of practitioners and artists into helping our communities,” she says. But it’s not enough to match the need.

Dossier

“History and Status of Prolonged Grief Disorder as a Psychiatric Diagnosis,” by Holly G. Prigerson et al., Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, January 2021. A detailed review explores the evolution of psychiatric views of grief over the 20th century, including current diagnostic formulations for prolonged grief disorder.

“Complicated Grief Therapy for Clinicians: An Evidence-Based Protocol for Mental Health Practice,” by M. Katherine Shear et al., Depression & Anxiety, October 2019. A detailed description of the evidence-based psychotherapeutic protocol developed by Katherine Shear looks at the treatment of complicated grief, also known as prolonged grief disorder, including ways of implementing its seven core themes.

Stay on the frontiers of medicine