Published On February 14, 2017

FOR NEARLY TWO DECADES, Angie and John Fitzgerald lived the good life, enjoying a happy marriage and flourishing careers. But several years ago, clinical depression helped tip John into a downward spiral. The aftereffects of an emotionally abusive childhood reasserted themselves, and as the U.S. economy faltered, he had several unsatisfying job changes. Angie helped her husband seek treatment, which included both counseling and medication, but he never rebounded, holing up in their condominium on the North Shore near Boston after he could no longer work. “He seemed to lose interest in everything,” Angie says. In a conversation shortly before his death, he told her he didn’t want to become more of a burden. “I assured him we were going to get through this,” she says.

Angie recalls that interchange as her only real clue that John might end his life. One day last September, she became alarmed when her repeated phone calls from work went unanswered. She rushed home and found her husband dead from an overdose of prescription antidepressants. He was 47 years old.

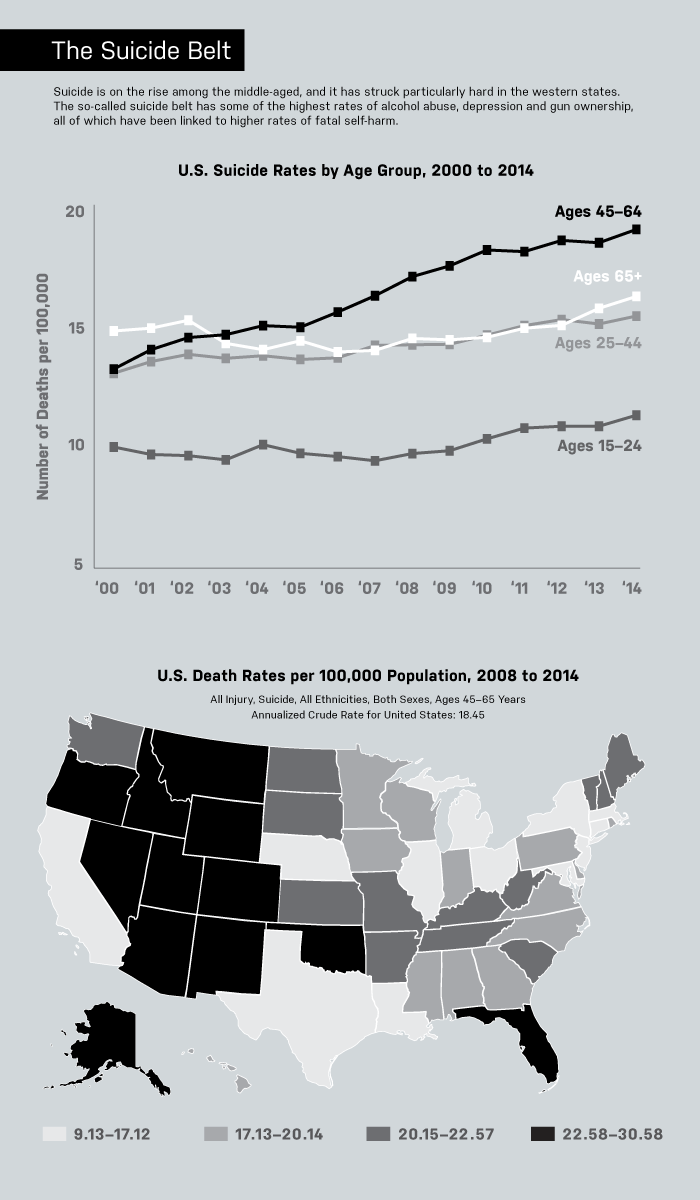

John Fitzgerald’s death came amid a sharp rise in suicides of middle-aged Americans—a departure from the past, in which the very old have been most likely to kill themselves. A report released by the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) last April looked at suicide rates from 1999 through 2014. Suicides surged 24% during those 15 years, and by 2014 the middle-aged accounted for the largest proportion of the deaths. Middle-aged women, ages 45 to 64, had a 63% increase, while the rate for men in the same age group rose 43%. Meanwhile, rates for men age 75 and older, a group that in the past had the highest risk of suicide, actually went down. In 2014, more than a third of the 42,773 people who killed themselves in the United States—the highest number ever, and more than those who died from breast cancer or car accidents or homicide and AIDS combined—were middle-aged.

Problems that often lead to suicide—mental disorders, substance abuse, a family history of suicide—are frequently complicated by other circumstances, say those probing this demographic shift. The rising number of cases may be fueled by disappointed expectations of social and economic well-being, a trend that has hit white baby boomers particularly hard. White men are proving especially vulnerable, as many of them come to grips with the realization that they’ll never be as well off as their parents have been.

But with so many factors involved, it’s hard to pinpoint exactly what is going on now, says NCHS statistician Sally C. Curtin, who co-wrote the April report. Nor is it easy to identify those in middle age who might be most at risk, says Craig Bryan, executive director of the National Center for Veterans Studies and assistant professor of psychology at the University of Utah. As scientists and clinicians struggle to make sense of what is occurring, several initiatives are seeking to find and dissuade those who may be considering suicide. A visit to the doctor often precedes an attempt at self-harm, and programs that train physicians to do routine screening for depression and other warning signs have had notable success.

FOR A 2014 STUDY published in Social Science & Medicine, Julie Phillips, professor of sociology at Rutgers University, sifted through eight decades of U.S. mortality data to offer ideas about why cohorts born after World War II, including baby boomers, may be particularly prone to kill themselves. In the study, funded by the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention, Phillips notes a “changing epidemiology of suicide” and suggests that explanations for this pattern extend beyond mental illness and other individual risk factors. Phillips argues that rising rates have also been shaped by the social and cultural upheavals that began in the 1960s, which continue to influence this population group. Boomers are more likely to be single, divorced or never married, and childless than earlier generations were—and being deprived of support from family members may increase their susceptibility to suicidal thoughts and actions.

Phillips also notes a decline among postwar cohorts in religious practice, another force that traditionally brought people together. A study published in 2016 in JAMA Psychiatry, based on data from 1996 through 2010, found that women who attended religious services at least once a week were five times less likely to commit suicide than women who never went.

Health problems, particularly those related to obesity, as well as financial and job insecurities that have risen in the wake of the recession of 2007 through 2009, have also hit boomers hard, Phillips says. Men in this group who, perhaps more so than women, are expected to support their families financially have proven especially vulnerable.

Historically, suicide rates have tended to rise and fall with the state of the economy. A 2011 report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found that rates spiked during the Great Depression (1929-1939), while a smaller percentage of people killed themselves during periods of economic expansion, such as the World War II years (1939-1945) and between 1991 and 2001, when the economy grew rapidly and unemployment was low.

Phillips and Katherine Hempstead, a visiting faculty member at Rutgers and senior advisor at the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, created a way to categorize different types of factors that contributed to suicide. They used data from the National Violent Death Reporting System, which draws from medical examiner and coroner reports, toxicology findings, death certificates and law enforcement records. They grouped suicides from 2005 to 2010 according to three major types of circumstances: personal, interpersonal and external. Circumstances such as illness, depression or substance abuse counted as personal; relationship issues, marital problems or the recent death of a loved one are interpersonal; and financial or job difficulties or legal issues are considered external factors.

The study, published in 2015 in the American Journal of Preventive Medicine, found that external economic factors, such as financial or legal difficulties, were present in 38% of all suicides for those aged 40 to 64 in 2010 (the last year for which the study has data), five percentage points higher than in 2005, when the economy was still growing rapidly. In contrast, the relative prevalence of suicides tied to personal or interpersonal circumstances remained stable or declined during the period. Hempstead sees these trends persisting in more recent data. “A lot of people feel like the economy has recovered quite a bit, but maybe those improvements aren’t being felt by everybody,” she says.

BEYOND ECONOMIC FACTORS, the rise in middle-aged suicides may be part of a larger portrait of dashed expectations. For those raised during the Depression or World War II, midlife has often been regarded as a time of personal and professional fulfillment. But something seems to have changed. Many white baby boomers aren’t just less well off than their parents, according to a study published in 2015 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, they are also sicker and dying sooner. A rising tide of mortality includes not only suicide but also a range of chronic health conditions, alcohol-related liver disease and overdoses, particularly from prescription opioid painkillers.

Those causes, along with an increase in economic insecurity, are among the suspected reasons for a rise in mortality rates for white men and women, especially those ages 45 to 54 with only a high school education or less, according to that study’s authors, Princeton University economists Anne Case and Angus Deaton, winner of the Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences in 2015. Mortality increased by 22% between 1999 and 2013 for this demographic group while it declined for middle-aged blacks and Hispanics during the same period. This quiet epidemic added up to a half million people, comparable to the number that lost their lives in the U.S. AIDS epidemic through mid-2015.

A separate analysis by the NCHS of suicide rates by race and ethnicity, also released last April, reinforces the idea that non-Hispanic white baby boomers are disproportionately affected. The study found that suicide rates for middle-aged white women, ages 45–64, soared 80% from 1999 to 2014—and was three to four times the rate for females in most other racial and ethnic groups. Suicides of middle-aged white males rose 59%, a jump larger than for any other male age group. In contrast, non-Hispanic black males of all ages became 8% less likely to die by their own hands during that period.

“The data suggests that the lives of white middle-aged adults have changed in unexpected ways in recent years,” says David Blumenthal, a physician and president of the Commonwealth Fund, a New York City–based foundation. Blumenthal also co-authored a 2016 analysis with senior researcher David Squires that builds on the work of the Princeton economists. Blumenthal and Squires found that suicide, substance abuse and liver disease accounted for almost half of the mortality gap for whites aged 45 to 54, with the rest blamed on lack of improvement across a broad range of other health conditions. “We are accustomed as a nation to making steady progress in the area of health,” Blumenthal says, but for middle-aged whites, “we are witnessing regression that has little precedent in the industrialized world over the past half century.”

DESPITE THE TOLL THAT self-inflicted deaths increasingly take, spending by the National Institutes of Health on suicide research and prevention has been stagnant, and the $73 million that went for such work in fiscal 2016 was only a fraction of the $586 million spent to fight kidney disease, for example, according to federal data.

Still, the recent surge in suicides has drawn increasing attention from policymakers, and the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) is one of several government agencies seeking to direct more resources toward reducing risks for working-age adults. Last year, SAMHSA awarded $2 million to four states to develop more robust, coordinated prevention strategies across local communities and health systems. The presidential federal budget proposal for the 2017 fiscal year requested a $28 million increase to fund similar grants.

And although its future may now be in doubt, the Affordable Care Act—by insuring 20 million people who had lacked health insurance and requiring that all policies cover mental as well as physical illness—offered hope that the recent increase in suicides might be reversed.

Moreover, research shows that almost half of adults who die by suicide have visited their primary care physician within a month of their death—and that those doctors may serve as the best frontline defense. In 2012, the National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention, a public-private partnership of more than 200 organizations supported by SAMHSA, launched a National Strategy for Suicide Prevention. Part of that program aims to improve suicide prevention in health care settings. Detroit’s Henry Ford Health System provides a model for such an approach, requiring all primary care and behavioral health physicians in its clinics and hospital emergency rooms to ask patients questions about depression, suicidal thoughts and sleep patterns, and direct them to appropriate care if a problem is detected. The results from the behavioral health department have been dramatic, with an 80% drop in the suicide rates of patients in its network from 2001 to 2010. Today, several hundred health systems around the country are working to implement similar programs, says Jerry Reed, director of the SAMHSA-funded Suicide Prevention Resource Center.

Interventions for adult males at risk of suicide, a demographic group least likely to seek out professional help, have also become a goal of prevention advocates. Innovative websites such as mantherapy.org and massmen.org provide men with a place to go for free, anonymous mental health screening and to resources for treatment and recovery.

A more controversial focus of suicide prevention efforts seeks to reduce access to lethal means. Adult men who commit suicide are most likely to shoot themselves, and for women, gun deaths rank a close second after poisoning, according to 2014 data. Several studies, meanwhile, have established that access to guns increases the chance of suicide and that many who try to kill themselves act on impulse and are more likely to succeed if a gun is available. A 2008 paper in the New England Journal of Medicine, for example, found that men were 3.7 times more likely to use a gun to kill themselves and women 7.9 times more likely in the 15 states with the highest rates of gun ownership, compared with the six states where gun ownership is lowest.

Means Matter, a campaign by the Harvard Injury Control Research Center at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health in Boston, promotes practices such as storing guns unloaded and locked as a way to cut down suicides. To date, however, only 11 states have laws that require locking devices for some firearms, and only Massachusetts mandates that all guns be stored with a locking device in place. Jerry Reed of the Suicide Prevention Resource Center, meanwhile, hopes that new federal and state rules designed to limit prescription opioid abuse could help reduce access to another common means of suicide—intentional overdoses of opioid painkillers.

Still, those who are intent on suicide are likely to find a way to get it done, and the April study from the NCHS noted that an increasing share of suicides involve methods other than shooting or overdoses.

For those on the front lines of suicide prevention, the question of how best to intervene remains a question of life or death. Patty Puline has founded several local programs as former injury coordinator for Pennsylvania’s Erie County Department of Health. She remains in favor of reducing access to lethal means, even with the challenges that it poses. If her 40-year-old brother hadn’t had access to a gun, she says, perhaps he wouldn’t have killed himself when his job at a manufacturing plant was threatened by layoffs.

Yet Puline is also a staunch advocate of one of the oldest anti-suicide strategies: paying closer attention to the people in your community. In the months before his death, her brother had put his beloved dogs to sleep, and given other classic indications of suicidal thoughts. “I was too late in understanding the signs and didn’t know how to talk to him,” Puline says. “I know now how much that could have helped.”

Dossier

“A Changing Epidemiology of Suicide? The Influence of Birth Cohorts on Suicide Rates in the United States,” by Julie A. Phillips, Social Science & Medicine, May 2014. Phillips examines eight decades of U.S. mortality data and the influence of social, cultural and economic factors on rising baby boomer suicide rates.

“Riding Morbidity and Mortality in Midlife Among White Non-Hispanic Americans in the 21st Century,” by Anne Case and Angus Deaton, Proceedings of the National Academy of Science, November 2015. Researchers document a deterioration in the morbidity and mortality of middle-aged white non-Hispanics in the United States between 1999 and 2013, and the potential economic causes and consequences of this trend.

Stay on the frontiers of medicine

Related Stories

- Predicting Suicide

Harvard psychology professor Matthew Nock has undertaken a large-scale study to understand why people take their own lives and find ways to assess those at risk.

- Deconstructing Happiness

Exploring 75 years of data, researchers trace the emotional highs and lows in the lives of hundreds of men and their descendants.

- The Black Dog

A mother details her internal struggles during her son’s battle with clinical depression