Published On July 23, 2006

MOST AMERICANS—INCLUDING MANY PHYSICIANS —seem not to have noticed, but type 2 diabetes has reached pandemic proportions. (Don’t be fooled by the conventional notion of pandemic diseases as explosive infections that burn across the planet killing millions.) According to a study published in the Journal of the American Medical Association in October 2003, approximately one of three children born today in the United States is at risk of developing the disease. Many won’t know they’re sick, at least for a while. But soon enough, the symptoms will be all too evident, with rapid weight gain or loss, extreme thirst, increasing hunger, slow-healing wounds and constant fatigue. If the condition is uncontrolled, it may spiral into devastating complications: rotting teeth and gums, heart disease, kidney failure, blindness, lost limbs and early death. Of the 200 million diabetics worldwide, at least 90% have type 2.

As the pandemic has spread, research has begun zeroing in on the causes, but no one yet understands exactly why a disease that dates to earliest history is only now threatening so many lives. “It must be something new, some new factor,” says Paul W. Ewald, a biologist from the University of Louisville who specializes in the evolution of infectious diseases. But what?

Most experts, including those at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), think the “something new” is our diet, because the correlation between obesity and diabetes is undeniable. But not all type 2 diabetics are fat. Indeed, people suffering from lipodystrophy, the almost total absence of fatty tissue, have a risk of developing type 2 diabetes that’s just as pronounced as it is for the obese. So the road between fat and diabetes isn’t a straight one, and there are some surprising stops along the way.

DIABETES COMES IN TWO BASIC VERSIONS. Type 1, which used to be known as insulin-dependent or juvenile diabetes, was invariably fatal until the advent of insulin injections. This version of the disease involves autoimmune destruction of the beta cells in the islets of Langerhans in the pancreas, which produce the hormone insulin. (By the time blood sugars have begun to rise, 80% to 90% of the beta cells may already have been destroyed.) With too little insulin, the body cannot process glucose and other nutrients into energy to feed the organs and muscle tissue. Unused glucose builds up in the blood and causes tissue damage while muscles starve.

In type 2, the course of the disease is much slower. Type 2 diabetes doesn’t destroy insulin production in the same way as type 1, although, for reasons not yet known, type 2 does damage beta cells and reduce insulin production. But the principal problem is insulin resistance—the body is unable to use insulin in the bloodstream to convert glucose into energy. Glucose builds up, just as in type 1, to similarly dire effect. But type 2 diabetics also have other potentially devastating problems—obesity, high blood pressure and abnormal blood fat levels, all of which combine to increase the risk of heart disease and stroke.

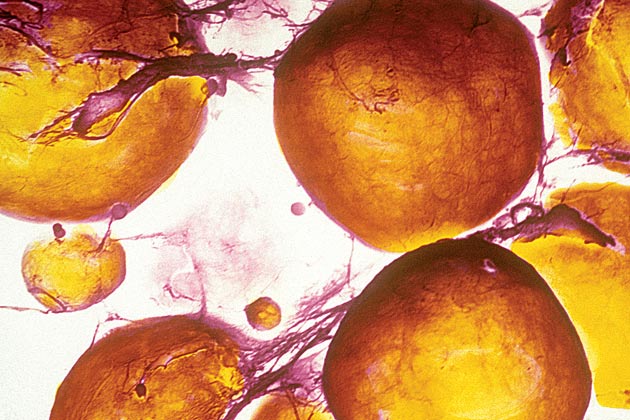

In simple terms, the body of an insulin-resistant person has run out of places to store fat. The normal repository is fat cells, and there are plenty of those—typically between 25 billion and 50 billion, some subcutaneous (beneath the skin) and some visceral (under the peritoneal membrane in the abdominal cavity). The body must either build more fat cells or store the additional fat in existing cells.

As long as the body is able to keep adding cells, says Nikhil Dhurandhar of the Pennington Biomedical Research Center of Louisiana State University, you may look lumpy and unattractive, but you probably won’t be threatened with insulin resistance and diabetes—because the fat has somewhere to go. Yet, for reasons not yet well understood, some obese people don’t seem able to develop additional fat cells, and more and more fat keeps pouring into existing cells.

Soon, the body’s fat cells are full to overflowing, and fatty acids begin leaking into the bloodstream. Excess fat may be deposited into the liver, causing a condition known as steatohepatitis (fatty liver disease), and infiltrates muscle cells, which may increase insulin resistance and even affect the functioning of the insulin-secreting cells in the pancreas. Worse, the overfilled cells serve as biochemical pumps, producing hormones and immune-system chemicals such as interleukins and tumor necrosis factor alpha. Known as pro-inflammatory cytokines, these substances are normally a critical part of the body’s response to acute infection. But in diabetics, perversely, an inflammatory response is triggered, and the body turns against itself.

Inflammation is a series of responses that evolved largely to defend the body from such acute problems as germs and injuries. If you’re attacked by a respiratory virus, you may develop a fever that produces a body temperature too high for the germs; if you sprain your ankle, the resulting inflammation helps keep your ankle immobile so healing can occur. But a steady, low level of inflammation, exactly the sort produced by overstuffed fat cells and the chemicals they pump out, is another matter. Normal fat is a necessary energy reservoir. But in diabetics, fat itself acts as a pathogen.

How could any species evolve such a response? How could fat, essential for survival, come to be an enemy? Part of the answer involves how we live today, under conditions unprecedented in our evolutionary history. Fast food and soft drinks containing massive doses of sugar confront our bodies with an excessive, energy-dense diet we’ve never before experienced. Meanwhile, we drive cars, sit in front of computers and use self-propelled lawn mowers and vacuum cleaners. The combination of supersize portions and inactivity makes us overweight and impairs our health. These conditions are, in Ewald’s words, something new to the human species.

Yet it’s hardly news that we’re getting fatter, and it’s hardly the only explanation for the explosion of type 2 diabetes. For one thing, even the constant ingestion of sugar and fat doesn’t necessarily lead to insulin resistance and diabetes. According to Dhurandhar, there is increasing evidence that mild respiratory viruses called adenoviruses may contribute to obesity, but without causing diabetes. Dhurandhar began researching this connection in his native India, where he treated more than 8,000 obese patients, some of whom, among the most overweight, seemed to have been infected with the adenovirus SMAM-1. Curiously, these patients had lower cholesterol and triglyceride levels than the rest of the group. Dhurandhar’s research team later discovered that another human adenovirus, Ad-36, promotes obesity in animals while improving insulin sensitivity by increasing the number of fat cells. With more places to store fat, lipid levels don’t go up, and without increased lipid levels and insulin resistance, even very obese people may not develop diabetes.

Yet for those, obese or not, whose fat storage is used up, diabetes poses a growing threat. What’s more, some researchers now feel that any chronic inflammation, such as periodontitis, or gum disease, may aggravate, or even help begin, the process leading to the disease (see “A Deadly Synergy”). So, stopping diabetes may mean stopping the damaging inflammatory cascade that elevates lipids and produces systemic disease. Swollen fat cells have to be prevented from discharging their contents into the bloodstream, and other factors that raise lipid levels, such as severe periodontitis, must be brought under control.

Of course, exercise and a healthy diet help reduce blood lipids. And curbing systemic infections, even such remote and apparently unrelated conditions as gum disease, may also help curb the dangerous cycle that pumps pro-inflammatory cytokines into the blood, raises lipid levels and pushes people toward type 2 diabetes. Yet the more one ponders type 2 diabetes, the stranger and more mysterious the condition becomes.

Unlike an acute infection, which has an obvious cause, the knot of factors leading to this devastating illness still seems hopelessly tangled. It is caused by obesity, but only certain kinds; it is pushed along by the very defenses the human body has evolved to protect itself; it seems to involve a process whereby, under certain circumstances, fat may act like a pathogen, and pathogens (for instance, those involved in gum disease) may act like fat, provoking a destructive immune response. And no one knows exactly how all the pieces interlock. As the pandemic (and waistlines) inexorably expands, the search for answers will only become more urgent.

Dossier

“Role of the Adipocyte in Metabolism and Endocrine Function,” by Steven R. Smith and Eric Ravussin,Endocrinology, eds. Leslie J. DeGroot and J. Larry Jameson, Elsevier Saunders, 2005. A technical but engrossing account of the dangers of leaky fat cells, their production of inflammatory chemicals, and the link between fat and insulin resistance.

“Periodontitis and Diabetes Interrelationships: Role of Inflammation,” by Anthony M. Iacopino, Annals of Periodontology, December 2001. One article in a series by Iacopino, often with Christopher Cutler, exploring the relationship between gum disease and diabetes.

Stay on the frontiers of medicine