Published On September 22, 2008

LIKE MOTION PICTURES A CENTURY AGO, video games have leaped into public consciousness as an entirely new medium. And just as millions flocked to see projected images in the early film palaces, an entire generation of game players is now poised before much smaller screens, not merely watching but participating, often in competition with other enthusiasts. Yet although games entertain, they have other purposes too, and in the realm of health care, they are taking on an astonishing variety of roles.

Players can take aim at cancer cells or social inhibitions. Or, if they’re going after more traditional targets—asteroids and spaceships—it could be with a twist, engaging an autistic teenager, say, whose decisions about when to shoot and when to hold fire may help develop impulse control. Nutrition, fitness, rehabilitation—all are now being packaged as games.

Then there’s the really serious stuff, such as disease outbreaks in a game’s cyber population that teach researchers what might happen during an actual pandemic. Or a game that challenges amateurs to pursue research objectives that have so far escaped professionals in the rarefied field of protein folding. “This could be a whole new way of doing science,” says the lead developer of Foldit, the protein game, whose progenitors can envision an AIDS vaccine or a new drug for Alzheimer’s.

None of these games, of course, is going to become the next Grand Theft Auto IV, which grossed $500 million during its first week on the market last summer. But within this niche of health and medical games, the majority of which are being funded by nonprofits and government grants (totaling about $50 million per year by 2010), sales and profits tend to be much less important than behavior change or research gains.

“The potential applications of games to improve health care are significant,” says Chinwe Onyekere, a program officer at the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, which recently awarded more than $2 million to help 12 university research teams study whether games can help players make healthier lifestyle choices. “Games are in so many people’s homes, and they cut across lines of race, ethnicity and socioeconomic status.”

Considerable academic research is already attempting to document the effect of health games as learning tools, and although results so far are inconclusive, advocates are convinced that games’ addictive nature, together with their physical and mental requirements, can be put to persuasive use. Even insurance companies are getting into the act. Aetna and Humana are experimenting with what the industry calls “casual” games, episodes that last just 15 to 20 minutes and are so easy to control that they can be played on cell phone keypads. And Cigna is exploring the use of Second Life, a virtual world in which players create characters, places and events and interact with one another, as a forum for educating members about health and nutrition. Debra Lieberman, director of the Health Games Research program at the University of California, Santa Barbara, thinks such innovations are only the beginning, and that many more will follow as success encourages funding from both the public and private sectors. “Momentum is picking up fast,” she says.

COURTESY BLIZZARD ENTERTAINMENT

DISEASE CONTROL

In September 2005 an unexpectedly virulent virtual disease swept through the densely populated cities of World of Warcraft. The video game’s creators at Blizzard Entertainment had unleashed the virus to challenge advanced players, who risked infection and the loss of hundreds of points by engaging in combat with a winged serpent called Hakkar. What no one expected was that the virus would break out of Hakkar’s cave. Despite efforts to quarantine those who were infected, the disease spread, causing high casualties and social chaos.

To World of Warcraft player Nina Fefferman, a professor at Tufts University, and her student Eric Lofgren, that virtual pandemic seemed a perfect chance to understand what might happen in the real world. With 4 million players, the game provided a wealth of data about human behavior, with which epidemiologists could now refine their mathematical simulations. Characters spread infection by teleporting between virtual locales, much like real people who hop transcontinental flights. Even virtual pets can get infected and pass along the virus, just as real ones could during human epidemics.

When Fefferman and Lofgren published their research, it caught the attention of the U.S. Departments of Defense and Homeland Security, which are now helping to fund additional research. The scientists are looking at how they might implant controlled disease outbreaks within other games to study players’ responses. “Lots of online games have the potential to teach us all kinds of things about sociological behavior,” Fefferman says.

COURTESY KAISER PERMANENTE

CASE CLOSED

The Amazing Food Detective, heroine of an eponymous online game from HMO giant Kaiser Permanente, is retro but hip—a distaff, trench coat–clad gumshoe who looks as if she just stepped out of a film noir. She guides players in the game’s targeted 9-to-11-year-old age range through mysteries involving eight children, including Michael, a chubby couch potato who sits at home in front of the tube. Players click on various interactive objects in the room until they find one—a soccer jersey draped over a chair, say—that inspires Michael to get moving. Once he dons the shirt, he’s seen happily practicing kicks and passes outdoors. As the detective stamps CASE CLOSED on the file, she explains that “doing something active gives you more energy.”

Other mysteries involve children who skip breakfast, eat too much or don’t consume enough protein. The reward for solving each mystery is access to three minigames, which reinforce the story’s theme. There are also links to healthful recipes, Internet scavenger hunts, experiments and exercises. And if playing a computer game seems an odd way to encourage kids to exercise, there’s this feature: The game shuts off after 20 minutes, and players can’t get on again for an hour. Though there’s no published research so far showing that it works, extensive focus-group testing suggests kids like the idea of the game, now used in 5,000 public schools, while teachers, in a Scholastic survey, noted that students who played the game seemed to be eating better and becoming more active.

COURTESY OF MINDHABITS

DEFENSE STRATEGIES

What you think of yourself—and your perception of how others think of you—is a learned response, suggests Mark Baldwin, professor of social psychology at McGill University in Montreal. Stress, for example, is often a reaction to a social threat; you imagine people are laughing at you or doing something else that makes you feel insecure. It takes just an instant for many such thoughts to occur to you, and eventually, after countless repetitions, the brain gets trained to respond in a particular way—leading people to shrink from risks or unfamiliar situations.

MindHabits Trainer, designed around Baldwin’s theories, offers four simple exercises to reduce stress and boost self-confidence. In the Matrix, a player confronts a screenful of dancing faces, most of them frowning. To win points, the player must quickly click on the much rarer smiling faces. By practicing the mental operation of disengaging from a social threat—the frowning faces—players can learn to deal with stress in the workplace and elsewhere.

“What we’re doing in this game is blocking feelings of rejection or criticism that are key triggers of stress,” Baldwin says. Another MindHabits exercise requires players to load and repetitively click on their names and other personal information matched to images of social acceptance, such as warmly smiling faces, to increase self-esteem and reduce feelings of aggression. In a test, the Matrix reduced levels of the stress hormone cortisol by 17% in a group of telemarketers, who played the game five minutes every day for a week. The workers also became more productive.

COURTESY AUGUST ZINSSER

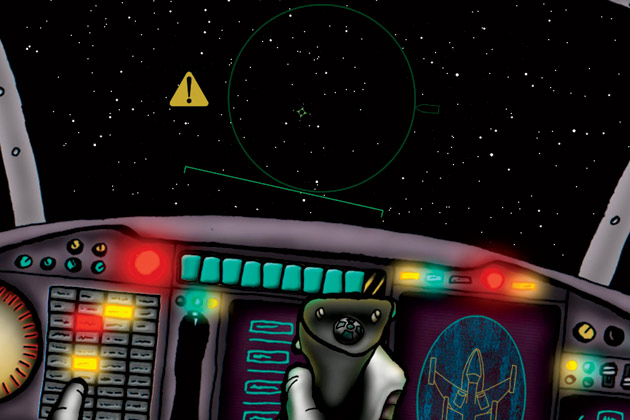

ACTING ON IMPULSE

In Maritime Defender, part of the video game Astrolopolis, a player steers a spaceship, fires on meteors and makes snap decisions about whether other vessels are friend or foe. That may sound like child’s play, but it also gauges what Matthew Belmonte, assistant professor of human development at Cornell University, calls “inhibitory function”—the ability to curb an impulse. That game, used in conjunction with an electroencephalogram, could help assess an autistic player’s hand-eye coordination.

Astrolopolis is designed for autistic children, who tend to become anxious when they have to deal with people and perform in testing situations. “There are only a certain number of ways a computer can interact with you, and you can be ready for those,” Belmonte says. “That’s a very comfortable environment for a person with autism.”

Belmonte has spent the past year working with undergraduate gamers at Cornell and other colleges to build features into the game that not only keep players involved but also collect behavioral data and potentially motivate behavioral change. “If we can use the game to measure the capabilities of people with autism, then the next step will be to add features that might actually stretch those capacities,” says Belmonte, who hopes to complete the game and begin trials of its effectiveness by year’s end.

COURTESY HOPELAB

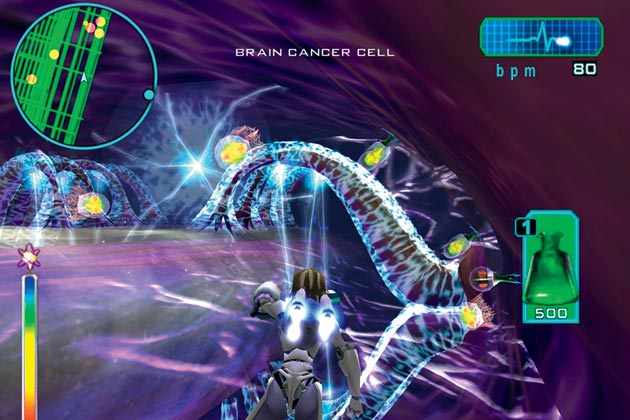

KICKING CANCER

Teenagers with cancer often stray from treatment regimens, so the goal of Re-Mission is to help these patients overcome the obstinacy of adolescence. “This is stealth learning,” says Steve Cole, vice president of research at HopeLab, the Redwood City, Calif., nonprofit that developed the game. “The things that happen inside the game get into players’ heads and change the way they approach the world.”

Re-Mission features a “nanobot” named Roxxi, who travels through the body blasting away at tumor cells. Players rack up points by helping her ensure that virtual patients are swallowing pills, taking stool softeners to prevent bowel perforations and practicing good oral hygiene to avoid mouth sores. If Roxxi fails to kill off every cancer cell in her path, there can be a recurrence—bad for players’ scores and, potentially, their health. But when players lose, Roxxi powers down and they can try again.

For a study published in the August issue of the journal Pediatrics, researchers randomly assigned Re-Mission to half a group of patients and the rest a different video game. Re-Mission players took 62% of their prescribed antibiotic doses; the others just 53%. That’s a significant improvement, say the researchers, who note that Re-Mission players also maintained higher levels of chemotherapy medication in their blood, suggesting they were taking those pills too.

COPYRIGHT © 2008 ARCHIMAGE, INC.

FOOD FIGHT

The notion of using computer games to modify behavior is nothing new to Tom Baranowski, a psychologist and professor of pediatrics at the Children’s Nutrition Research Center within the Baylor College of Medicine in Houston. The key, says Baranowski, who has been studying the potential of games since the 1990s, is the extent to which players lose themselves in the action. ‘The rich immersive capabilities of video games allow players to participate as characters inside a story,’ he says. ‘They learn from what feels like actual experience.”

Escape From Diab, which Baranowski helped develop, is the subject of a yearlong study, funded by a grant from the National Institutes of Health, that targets overweight children at risk for type 2 diabetes. The main character, Deejay, leads players into a world in which the evil King Etes has banned exercise while fattening up citizens on free junk food. Deejay guides players through goal-setting, problem-solving and other activities on behalf of the characters, who, by eating right and exercising, defeat King Etes. The study, involving 150 players, measures whether they consume more fruits and vegetables and become more active and physically fit. Early results are promising, says Baranowski. “In coming decades, much of health education is going to be delivered via games,” he says.

COURTESY NINTENDO

REHAB WITH A REMOTE

Nintendo doesn’t market its Wii video game system for occupational therapy, but it’s become known as Wiihabilitation on the wards of the Walter Reed Army Medical Center in Washington, D.C., where soldiers returning from the Middle East and recovering from combat injuries tend to be in the 19-to-25 age range. Wii players get to box, golf, bowl or swing a tennis racket or baseball bat, going through the motions of each sport while waving a wireless controller that directs animated on-screen athletes. The games provide so much distraction that patients tend to overlook the intense discomfort of therapy while gaining endurance, strength, coordination and concentration. Moreover, says Major Matthew St. Laurent, chief of occupational therapy at Walter Reed, two patients can play together, fostering social interaction, which is another essential part of recovery.

To test the effectiveness of video games as a rehabilitation tool, researchers at the University of South Carolina plan to have stroke patients try Wii Fit (which includes step aerobics, running, strength training, yoga, snowboarding, skiing and hula-hooping) and other video games. Then they’ll evaluate the impact on players’ mobility, balance, posture, weight-shifting capabilities and brain activity. One goal of the study is to identify specific ways Wii therapy can be used to aid recovery not just in a clinical setting but also at home.

ANIMATION RESEARCH LABS, UNIVERSITY OF WASHINGTON

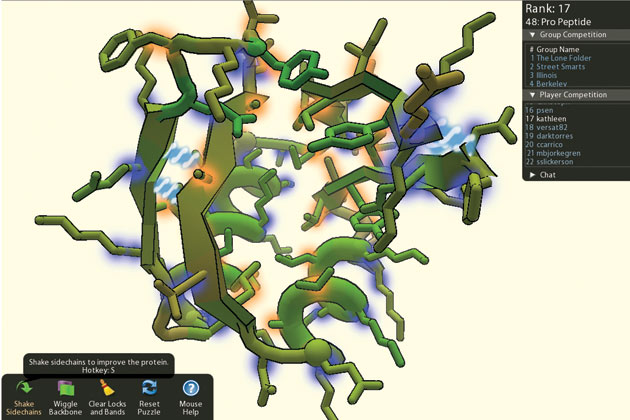

PROTEIN PUZZLER

For all of its enormous power, computer technology hasn’t been able to solve an essential biological mystery—how proteins transform themselves from long, unwieldy strings of molecules into compact shapes so they can fulfill specific functions, such as sending signals through the brain and transporting nutrients through the blood. Even less is known about protein misfolding, implicated as a cause of some 20 diseases, including Alzheimer’s and many forms of cancer.

So, the inventors of Foldit have turned the job over to the shared intelligence of online players. Guided by a cartoon version of a University of Washington scientist who helped develop the game, players confront colorful, snakelike, 3-D images of protein structures and are asked to rotate, twist and wiggle the configurations down to shapes in their most compact form, with the fewest gaps and holes. Points are awarded for successes and subtracted for mistakes as players, competing against one another, try to solve each puzzle.

Since the game’s launch this past May, it has drawn tens of thousands of participants, says Zoran Popovic, head of the game’s development team and a University of Washington associate professor of computer science and engineering. Players practice on the handful of the more than 100,000 human proteins whose structures are understood, then move on to more difficult proteins, for which the optimal folding isn’t known. Though there have been no breakthroughs yet, the hope is that players might come up with structures that could either stabilize the normal folding of a protein or disrupt pathways that lead to misfolding.

Stay on the frontiers of medicine