Published On January 15, 2013

IN 1878 THE SISTERS OF PROVIDENCE OPENED ITS FIRST Seattle hospital, with Mother Joseph, known as “the Builder,” designing and supervising construction of the three-story brick building. Thirty years later, Nils Johanson, a surgeon and Swedish immigrant, persuaded 10 of his fellow Swedish-Americans to buy $1,000 bonds so that he could open Swedish Hospital, a 24-bed facility in a former Seattle apartment house. Then for much of the next century, the hospital systems that grew from those modest beginnings competed against each other. Swedish Health Services was smaller but highly regarded, with five hospitals and 100 primary care and specialty clinics. The regional powerhouse Providence Health & Services had 27 hospitals and other facilities stretching over five states.

In 2011, however, with the economy slack, medical costs rising, and insurance companies and the government reducing reimbursement, both health systems were feeling the strain. Amid revenue shortfalls and job cuts—and with the reforms of the U.S. Affordable Care Act looming—the two historic rivals announced they would join forces. “Both hospital systems saw the need to have a larger geographic spread to serve our communities,” says Arnold Schaffer, chief executive of Providence’s new Western Washington division, which includes all Swedish operations. And while it remains uncertain exactly how the federal law, also known as Obamacare, will affect hospitals, it mandates a reduction of $155 billion in U.S. payments for hospital services through 2019. “We’re assuming we’re going to get paid less,” Schaffer says.

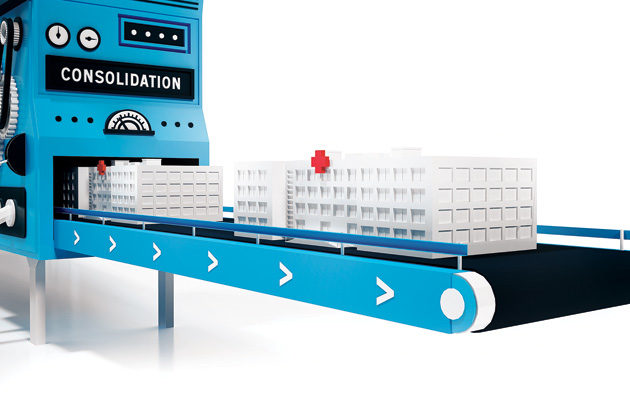

For similar reasons, hospitals around the country are consolidating at a rapid pace, not just in their local markets but also across state lines. During the first nine months of 2012, at least 58 hospitals were involved in hospital mergers or acquisitions, according to Irving Levin Associates of Norwalk, Conn., which tracks health care transactions. Joint ventures, clinical affiliations and other types of transactions that stop short of full mergers have also become commonplace. “Everyone is talking to everyone, because size matters now,” says Lisa Goldstein, an associate managing director who follows nonprofit hospitals for Moody’s Investors Service. “We expect to see an active consolidation trend during the next two years.”

This isn’t only a matter of hospitals buying each other, Goldstein notes—they’re also being approached by health insurance companies and private equity firms that in many cases are taking ownership stakes. Hospitals are also purchasing nursing homes and physician groups. But it’s deals among hospitals that are really changing the landscape. “Organizations are collectively reorganizing themselves to meet a changing business model for service,” says James Blake, managing director of Kaufman, Hall & Associates, a consulting firm in Chicago. Hospital systems are preparing for federal changes that will bundle payments for hospital and physician services and emphasize quality of care. “Hospitals may be operating just fine in the fee-for-service world, but there’s a new world coming,” he says.

Yet there’s no guarantee that the latest wave of mergers will achieve the desired results. Integrating distinctly different cultures and operations can pose major issues, and projected financial benefits may not materialize. Meanwhile, research suggests that bigger isn’t always better: Past consolidations have led to price increases for hospital services that are passed along to consumers. But there’s reason for cautious optimism: In this financially strained landscape, size can have its benefits, such as a greater range of patient services and the promise of better coordinated care, as well as more bargaining power with insurers—which at least has the potential to drive down supply costs.

THE FEDERAL HILL-BURTON ACT, PASSED IN 1946, revived public spending on health care after years of neglect during the Depression and the Second World War. One goal was to put a community hospital in every county, and the resulting boom in construction achieved that objective in about 1,200 counties that had never before had a hospital. The law also guaranteed hospital care to citizens who couldn’t pay. During the 30 years that Hill-Burton was in effect, hospitals established themselves as corporate entities with established credit ratings that could fund their own growth by issuing bonds. Meanwhile, the introduction of Medicare in 1965 cast the U.S. government as a primary revenue source for hospitals.

During the 1970s, rising financial pressures on hospitals—and rapidly escalating federal costs—led to legislation supporting an alternative model for health care. Health maintenance organizations attempted to control expenditures by enrolling people in health plans that restricted which hospitals and physicians they could choose. And though that earliest incarnation of “managed care” ultimately failed to catch on in much of the country, it led to an era of deregulation in which hospitals were no longer shielded from competition.

At the same time, technological advances meant that many procedures that had been performed in hospitals could be moved to outpatient settings. And by the 1990s, with revenue growth slowing for many hospitals, a spate of consolidation began. The number of U.S. community hospitals declined from more than 7,000 in 1970 to barely 5,000 in 1999—a number that has fallen only slightly since then, according to the American Hospital Association.

Yet now business deals involving hospitals seem to be on the rise again, both because of the flagging economy and in anticipation of Obamacare. As costs are scrutinized and reimbursement drops, larger systems will be able to spread costs and risks over a broader patient population, and it will be easier for them to tap capital markets for funds to develop the organizational and information technology systems needed to show that they’re providing effective care, says Goldstein.

In a review of nonprofit hospitals published in 2011, Moody’s found revenue growth of 5.3% that year, an improvement over the 4.2% growth rate in 2010 but very slow by past standards. The AHA reports that more than a quarter of all hospitals ran deficits on their operations in 2010. Hospitals face flat to negative growth in revenue from federal and state governments via Medicare and Medicaid, which together provide more than half of hospital income.

AT THE SAME TIME THAT THE GOVERNMENT reduces payments to hospitals, however, many institutions will benefit from a decrease in the uncompensated care they must provide. Having tens of millions more people with health insurance, thanks to the Affordable Care Act, should be the catalyst for a “robust increase” in revenues starting in 2014, according to the Moody’s report. That sets up a situation in which many hospitals that are struggling now could do much better soon—making them attractive acquisition targets for deep-pocketed acquirers. “There’s a fair amount of consolidation activity involving hospitals that are distressed and hospitals that are seeking partners because they don’t see a path to achieving their vision alone,” says Jeff Seraphine, president of the Delta Division of LifePoint Hospitals.

Based in Brentwood, Tenn., LifePoint is a publicly traded hospital company with 56 hospitals in 19 states. In 2011 the company announced a joint venture with Duke University Health System. In its first year alone, the joint venture, Duke LifePoint Healthcare, established affiliations with three hospitals in North Carolina and Virginia. But its biggest transaction to date is the purchase of Marquette General Hospital, a 315-bed tertiary care hospital and regional referral center serving Michigan’s Upper Peninsula. Carrying a heavy debt load, Marquette anticipated financial challenges and a significant reduction in Medicare payment revenue in coming years. Duke LifePoint said it would spend $350 million for major capital improvements and invest in boosting physician recruitment and expanding services.

“In most of our hospitals, we look to grow the number of services, not cut them,” Seraphine says. “Because we’re usually the only hospital in the community, we take that responsibility very seriously.”

IN ANY KIND OF CONSOLIDATION, newly joined hospitals must adapt to new ways of doing things. But some bedfellows are particularly strange and may require special arrangements. For example, in Seattle, when Providence and Swedish announced their tentative agreement in October 2011, they were careful not to call the deal a merger or acquisition but rather an affiliation. It was important for the hospitals to continue to operate separately, in part because Providence, as a Catholic hospital, had policies on reproductive services and receiving life-ending medications under the state’s Death with Dignity law that were at odds with those of Swedish, a secular institution. Swedish policies remained largely intact, though it no longer provides elective abortions in its facilities—referring patients, instead, to a Planned Parenthood clinic that Swedish helped fund. Swedish has not changed its policy on the Death with Dignity option. Its physicians may talk with patients about their options, even though life-ending medications can’t be taken in Swedish hospitals and Swedish pharmacies aren’t allowed to fill lethal prescriptions. “Providence has a policy that bars any discussion of Death with Dignity by its staff with patients,” says Robb Miller of Compassion & Choices, an advocacy group that supports terminally ill patients who want the option of self-administering life-ending medication. “But Swedish scored quite a victory in making its agreement with Providence without compromising its position on Death with Dignity.”

There’s also the matter of maintaining a hospital’s identity within a community—another issue that Providence and Swedish sought to address by agreeing to a structure that allows Swedish to keep its name. “The hospital had a 100-year history in the Pacific Northwest, so it is extremely well known and well loved,” Schaffer says. But the two systems are now working to improve how care is delivered, as well as to centralize back office and supply chain services—and trim expenditures. “We’re asking: How do we best serve the market together?” says Schaffer. “How many ambulatory surgical suites do we have and where, how many cardiologists or medical groups, so we can deliver on the promise of higher quality by reducing costs.” And though efforts to curb expenses have led to layoffs of only a few dozen employees, hundreds of other workers have chosen to leave, and those vacant positions are unlikely to be filled.

OTHER HOSPITAL COMBINATIONS, MEANWHILE, have led to deeper workforce reductions. Last summer’s purchase of St. Raphael’s Hospital by crosstown rival Yale—New Haven Hospital in Connecticut resulted in about 200 layoffs. But St. Raphael’s had been facing insolvency, its survival in doubt. Financially distressed facilities have also been attracting increasing numbers of private equity firms as owners. Nashville’s Vanguard Health Systems, for example, already owned 15 hospitals when it bought Detroit Medical Center and its network of eight hospitals in 2010. In the deal, it agreed to pay $417 million to reduce the system’s debt, invest an additional $850 million in DMC’s aging facilities and honor the system’s charity care mandate, though it made no similar pledge regarding future layoffs.

But private equity’s involvement could affect more than hospital employment levels. Such firms typically convert hospitals to for-profit corporate structures, and the need to operate hospitals in a way that will maximize earnings could lead the institutions into uncharted waters. Private equity firms also traditionally sell the investments in their portfolios within 5 to 10 years, and that could mean further changes for hospitals that in the past have seldom changed owners.

Historically, hospital mergers and consolidations have led to higher prices. A 2006 study by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation concluded that hospital consolidation that occurred from 1990 through 2003 raised hospital prices by at least 5%, with increases of 40% or more in markets that became most concentrated. Merged hospitals, meanwhile, achieved only modest cost savings. An update to the study published last summer had similar findings, and both studies found little evidence that quality of patient care improves. “We don’t know how the latest consolidation wave is going to play out,” says Martin Gaynor, a professor of economics and health policy at Carnegie Mellon University, who co-wrote the second report, though he suspects the impact will be negative. Much depends on the makeup of a local market, he says, in terms of the number of hospital and health plan competitors in determining whether merged hospitals can gain efficiencies or lower costs. A 2010 study commissioned by the National Business Group on Health that examined inpatient hospital care data for 65 U.S. cities also found that hospitals vary significantly in how well they manage costs. In the 16 cities where hospitals are providing high value for patient care, according to the study, researchers found a low correlation with the number of hospitals or health plans in the market, suggesting that some profitable hospitals don’t necessarily rely on market competition or increasing their leverage over private health plans to boost their operating margins.

Reducing costs and providing value, argues Providence’s Schaffer, are more compelling reasons for hospitals combining today than “market power by size” to increase leverage and higher rates. “Health reform and new payment models have put us in a different place,” he says. “Everything is about clinical integration, improving care, and reducing costs and variation.”

Even with cautions against consolidations, hospital mergers do offer advantages, such as economies of scale in purchasing power and the centralization of some functions. Vermont’s largest hospital, Fletcher Allen Health Care, announced it has saved more than $1 million after merging last year with Central Vermont Medical Center. Though the two hospitals maintain separate identities and workforces, their merger into one financial entity has allowed them to make bulk purchases on such items as medical supplies and develop a common electronic records system to coordinate in-state health care.

FOR THESE REASONS AND MORE, federal regulators are carefully scrutinizing whether hospital mergers are good business. “The big question is, how do we balance the potential benefits of integration and efficiencies against the loss of competition?” asks Jeff Perry, assistant director of the Bureau of Competition at the Federal Trade Commission. Perry says the FTC is currently investigating more than a dozen proposed mergers, and in 2012, the commission successfully blocked an Ohio hospital merger between ProMedica Health System and St. Luke’s Hospital that the FTC found would “substantially lessen competition” in the Toledo area and probably result in “higher health costs for patients, employers and employees.” (ProMedica filed an appeal in the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit in July.) Another FTC action, challenging the merger of two hospitals in Albany, Ga., is being considered by the U.S. Supreme Court.

State regulators are also taking a close look at proposed hospital combinations. In New Jersey, the purchase of Pascack Valley Hospital by Hackensack University Medical Center and Texas-based investment partner LHP Hospital Group was slowed by a four-year legal battle with two neighboring hospitals that charged that reopening Pascack, which several years ago shut down all operations except its emergency room, would weaken the other hospitals financially and add more hospital beds in a county that already has a surplus.

Regulatory hurdles are making it increasingly difficult to complete proposed mergers. In 2011 as many as half of announced transactions failed to move forward. And other mergers, though completed, ultimately fail. In 2008 in New York City, hospitals at New York University and Mount Sinai, for example, called off their combination after a decade. Such failures make many hospitals wary of traditional takeovers. They may opt, instead, for affiliations and strategic alliances that allow them to expand without giving up ownership.

Tiny 14-bed Cook Hospital in rural Minnesota is wrestling with its future in what its chief executive officer, Al Vogt, dubs the “Wild West of health care reform.” The hospital, which joined with a nursing home, wants to create clinical partnerships with larger hospitals. “There’s no reason why a small facility can’t partner with larger places, particularly by using electronic health records,” Vogt says. “The new rules are changing the landscape, but we don’t want to merge with anyone.”

Dossier

High Value for Hospital Care: High Value for All?, Milliman, commissioned by the National Business Group on Health, June 2005. Using data from commercial insurers, researchers analyzed hospital cost drivers in 65 cities, identifying 16 hospitals in different regions that are profitable without charging disproportionately higher amounts to commercial payers for inpatient care.

“Privatization of Hospitals: Meeting Divergent Interests,” by Thomas Weil,Journal of Health Care Finance, Winter 2011. Weil notes that the U.S. privatization trend could mimic that of Germany’s tiered hospital system: investor-owned hospitals for the wealthy, a majority of inpatient care provided by nonprofits, and economically deprived patients admitted to government-sponsored hospitals.

Stay on the frontiers of medicine