Published On December 19, 2014

1348: Quarantine in Venice

The second bubonic plague rages in Europe from 1347 to 1352, and kills a quarter to one-third of the population (25 million people), as well as at least another 25 million in Asia and Africa. As the most bustling port on the Mediterranean Sea, Venice is especially devastated. The city introduces one of the earliest formal systems of quarantine, requiring ships, goods and people to wait 40 (quaranta, in Italian) days before entering. The idea is based on a mistaken theory that communicable diseases are transmitted by pestilential air. The quarantine may have helped some, by preventing contact with infected people and objects, and also since 40 days was long enough to allow the fleas carrying Yersinia pestis, the plague bacterium, to die.

1353: Scenes from the Black Death

Giovanni Boccaccio, whose father died during the plague, uses the epidemic as the backdrop for his Decameron. The collection of 100 short tales of love, wit and valor all are contained within a larger frame: a story in which 10 nobles isolate themselves in a country estate, passing their self-imposed exile while plague rages through nearby Florence.

1423: Rise of Lazarettos

Quarantine measures are expanded with the opening of plague hospitals for the sick and suspect. They are called lazarettos (from “lazar houses”), in the spirit of Jesus treating Lazarus, who was commonly but mistakenly believed to have suffered from leprosy, another disease long subject to quarantine. Lazarettos were often on islands, or otherwise far enough away from towns to isolate the sick from the healthy, but also close enough that the sick could be transported there. The plague slowly abated but large outbreaks recurred over the next 300 years.

1656: Rome cordons off Trastevere

After a fresh spasm of bubonic plague kills 100,000 in Naples, Rome cordons off the Trastevere slum and the Jewish ghetto. Measures are harsh: The city patrols the ghetto, draws chains across the Tiber River to block ships, detains the infected in a pesthouse on Tiber Island, executes those who escape and prohibits all public gatherings. The authorities do not, however, clean up the filthy, rat-infested streets. Some 10 to 20 thousand Romans die in the ensuing months. “Plague doctors” develop a primitive personal containment gear — a hooded, robed uniform featuring a mask that included a curved bird’s beak filled with dried flowers, herbs, spices or a vinegar sponge.

1793: Yellow Fever and Racism

Yellow fever comes to Philadelphia, then the capitol of the U.S., in 1793, killing 5,000 of the 50,000 residents and forcing some 20,000 to flee.Physician and founding father Benjamin Rush recruited blacks, whom he thought immune, to care for the sick and dead. Blacks died at the same rate as whites, but were accused of profiteering – which was described by free blacks Absolom Jones and Richard Allen in A Narrative of the Proceedings of the Black People, During the Late Awful Calamity in Philadelphia, in the Year 1793: and a Refutation of Some Censures, Thrown Upon Them in Some Late Publications. A quarantine lazaretto built in response to the epidemic still stands on the Delaware River.

1830s: Global Trade Creates Pathways

Globalization grows with faster transportation (through steamships and railroads), and facilitates the spread of cholera from India. Public health officials quarantine the sick, but by the midcentury some doctors begin to question the policy’s effectiveness, and explore alternatives. In the 1850s, a London physician named John Snow traces multiple cholera patients to a single tainted water source. Governments target marginalized groups, such as beggars, prostitutes, immigrants and political opponents, and hustle them into quarantine facilities or across borders.

1842: The Plague as Bogeyman

The capricious nature of epidemics fascinate writers of the macabre. In Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Masque of the Red Death,” the red death of the title is a fictional plague causing sharp pains, sudden dizziness and bloodsweats, and kills within an hour. A thousand and one nobles attempt to escape it by desporting in a remote abbey, but the disease finds them out. At the stroke of midnight, a masked figure — the Red Death itself — appears and kills them all.

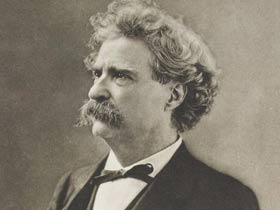

1869: American Exceptionalism

In the non-fiction Innocents Abroad, Mark Twain recounts his brush with cholera. A maritime quarantine in Athens detains Twain’s ship, which had previously docked in cholera-stricken Italy. Unwilling to wait out the quarantine, Twain describes how he and some companions cavalierly sneak ashore to tour Athens by moonlight, evading guard patrols and realizing that if caught he could face time in prison— a quintessential case of American rugged individualism trumping public health regulations.

1892: Immigrants and Quarantine

When a cholera epidemic afflicts ships entering New York harbor, poor Russian immigrants— largely Jewish—fleeing persecution in Czarist Russia are detained, while the upper-class passengers are not. Later, all passengers are quarantined, albeit in different conditions. The cabin class stay in a posh hotel on Fire Island, while the steerage class in wretched, crowded facilities on Hoffman Island.

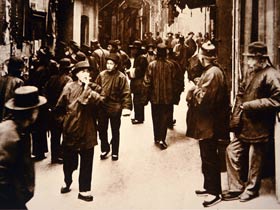

1900: Chinatown in the Crosshairs

In March, Chick Gin, a lumberyard proprietor, dies of bubonic plague in San Francisco’s Chinatown. Authorities cordon off the neighborhood, quarantine as many as 25,000 Chinese, demolish structures, forcibly inspect homes, plan to imprison thousands at Angel Island and strongly consider burning down Chinatown. A judge rules the quarantine racist and lifts it. The plague returns in 1907, but is effectively treated with rodent control and other preventive measures.

1907: Typhoid Mary

Still thinking that typhoid fever was caused by poor sanitation generally rather than contaminated food, public health authorities are baffled that affluent people in New York City are succumbing to the disease. They discover the afflicted households’ common denominator: Mary Mallon cooked for them and was inadvertently contaminating their food. She herself did not have the disease, but she was an asymptomatic carrier. She was involuntarily quarantined on North Brother Island from 1907 to 1910, and (after she had defied orders and returned to cooking for — and infecting — more people) from 1915 until she died in 1938.

1909: Hawaii’s Quarantine Hero

In 1912, Jack London recounts the true story of Koolau the Leper. After overthrowing Hawaii’s Queen Liliuokalani, the Provisional Government sent soldiers in 1893 to compel lepers who resisted being sent to a colony known to locals as “the grave of living death.” Ko’olau, a cowboy, had killed a deputy sent earlier on the same mission, then escaped and hid with his family and others in the rugged Kalalau Valley on the Na Pali coast. He shot and killed two of the soldiers sent to capture him, becoming a symbol of defiance against imperialism — and discrimination against the sick.

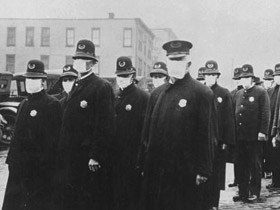

1918-1919: Spanish Flu

During World War I, a pandemic of virulent influenza virus infects as many as 500 million people and kills up to 50 million. It spreads so easily and quickly that traditional quarantines alone are ineffective. U.S. cities that fare best institute quarantines early and for a long time, and also ban public gatherings and close schools to break the chain of transmission. Among the families devastated by the “great influenza” were several writers who wove their experiences into fictional stories, including Thomas Wolfe’s 1929 novel Look Homeward, Angel, which recounts the death of his brother.

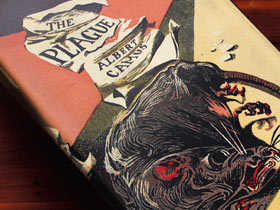

1947: Quarantine as Metaphor

An 1849 cholera epidemic in Algeria may be the basis of Nobel laureate Albert Camus’s 1947 novel The Plague, though he set it in the 1940s, possibly as commentary on the authoritarian regimes of the World War II era. In the story, officials do not understand the cause of the disease and respond inappropriately. Hospitals overflow, medical supplies run out, the town is sealed off. Those who try to escape are shot.

2003: SARS

Following an outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome, or SARS, in Asia and Canada, officials quickly isolate the sick and impose a quarantine on those potentially exposed to the disease. In Toronto, Canada, the quarantine of 23,103 people is voluntary; almost half break it in some way. In China, police cordon buildings, set up road checkpoints, put Web cameras in private homes and impose harsh punishments. Some rural populations protest that the harshest measures are aimed against them and that they have been stigmatized.

Stay on the frontiers of medicine

Related Stories

- Do Ebola Quarantines Make Sense?

Treating the epidemic means re-evaluating a public health tool with a storied past.

- Tech Meets Quarantine

New digital systems can help keep infectious agents at arm’s length—or further away.