Published On March 29, 2022

Massachusetts General Hospital’s clinicopathological conferences, or CPCs, are the shop talk heard around the world. On this afternoon in 2017, an audience of physicians has packed into the White Surgical Amphitheater for Surgical Grand Rounds. Allan Goldstein, surgeon-in-chief at MassGeneral Hospital for Children, lays out the case of conjoined twins, just 22 months old, and how a team of over 50 surgeons and 150 other health care providers prepared, planned and performed their separation—knowing that saving one girl meant the other would die.

A CT scan on the screen shows the twins joined from the chest down to the pelvis, an anatomy that uniquely shares a single liver, bladder, intestinal tract, urogenital and circulatory system. Separating them would be a tricky task, fraught with ethical challenges, and 20 other hospitals had refused to do the procedure. Now Oscar Benavidez, chief of Pediatric Cardiology at MGHfC, talks about meeting these tiny patients, describing how they played and sang, the one protecting the other, swatting away a needle when her sister got a blood test. The main concern was that Twin A, in addition to being noticeably smaller and weaker, had a tenuous cardiac status. She was missing a main pumping chamber of her heart and had irregular blood vessels running between her heart and lungs. An enlarged mesenteric artery, which normally supplies the intestine with blood, served as Twin A's lifeline, transmitting blood and oxygen from her sister—but it wasn’t enough. Twin A had developed recurrent pneumonia and her oxygen levels were dangerously low. She was dying, and because she shared a circulatory system with her sister, her death would leave little or no time to intervene to save Twin B, Benavidez says.

Brian Cummings, chair of the Massachusetts General Hospital Pediatric Ethics Committee, steps up to describe how he and his colleagues wrestled with the moral considerations of the case. Were the conjoined twins one person or two people? Is it ever morally acceptable to sacrifice one person over another? In an earlier court case, a judge had ruled that if one twin could survive, it was mandatory to operate, whatever the parents might want. But who ought to have the decision to perform separation surgery? The MGH committee ultimately left the decision to the girls’ parents, who made the agonizing choice to move ahead.

A flurry of slides—preoperative imaging and tactical models—show the surgeons’ plan to separate them. The physicians walk their audience through the 14-hour procedure. Although Twin A did die during surgery, Twin B not only survived but, there in the front row, sits with her parents in the audience, a tiny figure among the physicians. Just over a year older now, the girl smiles and claps along with the rest of the audience. According to her team, she now has a normal life expectancy.

That CPC would go on to provide the bones of Case 33-2017—one of "the Case Records of the Massachusetts General Hospital,” a staple of The New England Journal of Medicine since the 1920s. The medical story of these conjoined twins would join nearly 7,000 other cases that have, over the decades, developed a global following. “In 2020, Case Records was viewed more than a million times by readers from more than 200 countries,” says University of Pennsylvania pulmonologist Darren Taichman, deputy editor of NEJM.

The Case of the Lingering Tsunami

A young woman encounters a natural disaster and a rare condition.The 17-year-old had trouble breathing, severe right-side muscle weakness and couldn’t speak intelligibly when she was transferred to the U.S. hospital ship Mercy. Seven weeks earlier, she had been swept up by a tsunami, and MGH physicians on the Mercy found she had a collapsed lung and lesions in her brain probably caused by a bacterial infection. The diagnosis: tsunami-related aspiration pneumonia, or “tsunami lung,” caused by microbes in water and mud she had taken in. Treated with antibiotics, she improved steadily, and on the day she was discharged, she “burst into peals of laughter,” according to the Case Record.

From their earliest days, Case Records have been selected for their suitability as teaching tools, showing physicians how to diagnose and treat medical disorders and conundrums. Many cases have seared themselves into the collective memories of readers. There was the case of a 54-year-old man who went into cardiac arrest after eating too much licorice; the patient whose surgeon did the wrong procedure—carpal-tunnel surgery instead of trigger-finger release—and also operated on the patient's healthy hand; the woman whose mysterious symptoms traced back to a traditional Ayurvedic medication, which turned out to be giving her lead poisoning.

Every case record has to provide an educational opportunity.

“Every case has to provide a fundamentally significant educational opportunity,” says Eric Rosenberg, the sixth and current editor of Case Records, who directs the microbiology laboratories at MGH and is a professor of pathology at Harvard Medical School. While there may be fewer medical mysteries than in the 1920s—and diagnostic tools are significantly more advanced—even the most knowledgeable physicians encounter new puzzles, says Scott Podolsky, an MGH internist who is professor of global health and social medicine at Harvard Medical School and director of the Center for the History of Medicine at the Countway Medical Library at HMS. “There will always be emerging diseases, such as COVID-19, say, or conditions that arise from the effects of climate change,” he says. The Case Records discussions have also evolved to focus on emerging treatments and protocols, including diagnoses as they get further refined—what was called “lung cancer” in the past, for instance, is an ever-evolving collection of subtypes.

The Case of the Remedy Gone Wrong

An older woman’s health gets worse as her daughter

tries to help.The 76-year-old had abdominal pain and constipation, had lost weight, was disoriented and had considered suicide. A history of domestic abuse led to a diagnosis of post-traumatic stress disorder, and anti-anxiety medication helped.

But the search for an explanation of her abdominal pain hit one dead end after another. Finally, because her urinary porphyrin levels were high, and other test results pointed toward possible acute intermittent porphyria, she received four days of treatment with hemin. Yet the symptoms she had experienced, they saw, could also signify lead poisoning. It turned out that the patient’s daughter, who lived in India, had been providing dietary supplements thought to include traditional Ayurvedic medicines—which often contain lead, arsenic and mercury. Further testing revealed blood lead levels more than 20 times higher than normal. She received chelation therapy, and six weeks later, although her blood lead levels remained high, her abdominal pain was gone, she was eating better and her thinking had improved.

The greatest accolade for the Case Records may be how widely it has been emulated. Academic medical centers around the world now use the clinicopathological conference model, Rosenberg says, and many medical journals present mystery cases for readers to solve. The format has also caught on in consumer publications, such as the New York Times and Washington Post. Perhaps this popularity derives from Case Records being a fundamental kind of human puzzle—what has gone wrong with this person and how can the patient be made well? That puzzle strikes to the heart of medicine and helps set the craft apart from other disciplines.

When Walter B. Cannon was a Harvard Medical School student in 1898, he was subjected to a very different style of medical training—four-hour daily lectures that he found to be “dreary and benumbing.” Cannon envied his roommate, a student at Harvard Law School, who learned in a much more hands-on way, through real legal cases provided by his teachers. Cannon believed that the same type of educational format could work for medicine, too. At his urging, MGH internist and HMS professor Richard C. Cabot adopted what came to be known as the case method, in which students no longer regurgitated facts but discussed “actual cases of disease.”

Soon Cabot decided it wasn’t just students who could benefit from this approach, and in 1910, he teamed up with James H. Wright, the hospital’s first full-time pathologist, to present cases of deceased patients. They decided to put an expert on the spot, almost in the style of a modern game show, presenting the facts to house officers and visiting physicians and challenging them to come up with the correct diagnosis. Each Thursday at noon, a CPC was convened at the Allen Street Amphitheater—if an autopsy was in progress, the body was quickly shunted to the morgue and the autopsy table covered with a white sheet. A physician took the stage and worked through the patient’s history while those in the audience questioned him about his methods. He would finish by offering a diagnosis, which was then compared with the results of the patient’s autopsy.

These teaching exercises proved so popular that Cabot began publishing the cases. In 1915, four records a week were mailed to roughly 800 subscribers, who paid $5 a year. Then, in 1923, the inaugural “Case Records of the Massachusetts General Hospital,” edited by Cabot and his son Hugh, appeared in The Boston Medical and Surgical Journal (which later became NEJM).

Although Cabot had made his reputation as an expert diagnostician, it was important to him to show that even his medical knowledge had limits. Once, when a medical student asked during a CPC whether Cabot had considered rheumatic pneumonia as a diagnosis, he replied, “That’s a good idea; I never thought of it.” In fact, the student’s diagnosis was confirmed by autopsy. That idea of confronting fallibility also became an important contribution of the Case Records. “Too often in current medical literature we get accounts of brilliant successes, rather than of failures in diagnosis and treatment, which are of far higher educational value,” noted an editorial in the Boston Medical and Surgical Journal a few months after Case Records launched.

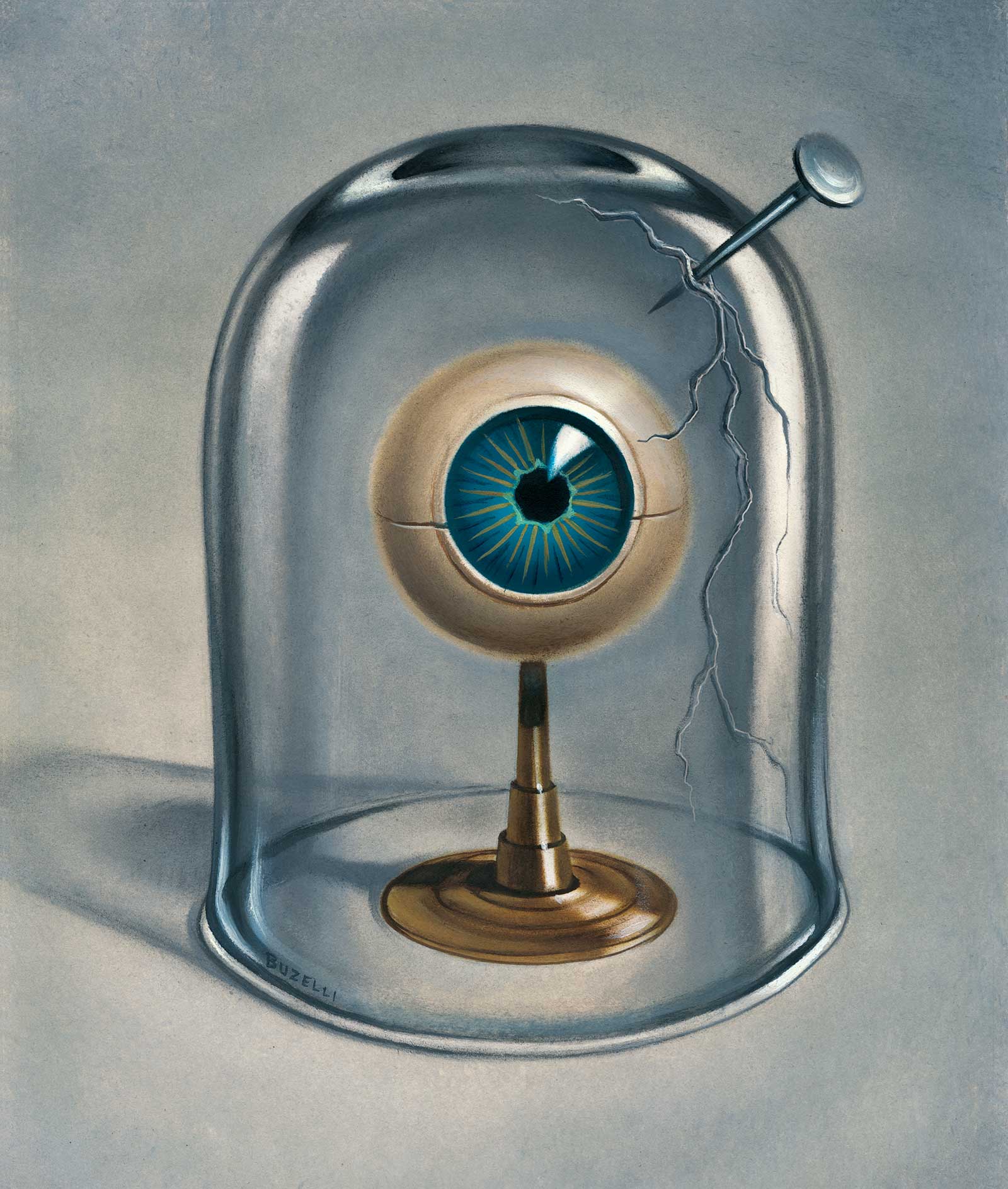

The Case of the Eye Transfixed

A lawn maintenance accident leads to a perilous surgical journey.The 27-year-old was in agony. While maintaining his yard, the weed whacker he was using had kicked up a long nail that shot into his right eye, and just trying to open it caused excruciating pain.

As his doctors approached treating the injury, they worried that the embedded nail might be the only thing preventing a cascade of brain damage, and pulling it out could cause a life-threatening hemorrhage. Advanced CT imaging couldn’t reveal whether the nail had punctured the internal carotid artery.

One option, bringing its own catastrophic risks, was to drill into the skull and also make an incision in the neck, providing access for emergency repairs. Finally, though, with two surgeons standing ready to make those cuts, a third gently pulled out the nail—and nothing happened. Even the eye was saved. With a course of antibiotics to prevent infection, the patient was released from the hospital, and within eight weeks, his vision was back to normal.

The Case Records soon grew into a medical institution. Cabot edited them until 1935, choosing the cases and then discussing them himself, often without preparation. The next three editors followed the same model. It wasn’t until 2002, when the reins were taken by Nancy Lee Harris, a hematopathologist at MGH, that the formula saw changes. Cases had historically focused on mystery diagnoses and their solutions, but while Harris was discussing the project one night with her husband, a radiation oncologist at Dana-Farber Brigham, “he pointed out that because laboratory medicine and imaging had become so good at uncovering a diagnosis, that was no longer the biggest problem clinicians faced,” Harris says. Spotting straightforward conditions had become much easier, and many of the cases presented at CPCs were now “zebras”—rare medical problems that few physicians would ever see. Harris announced that Case Records would strike into new territory—adding complex diseases where a patient history could help show other physicians new treatments or approaches to care.

These days, Rosenberg and his five deputy editors meet once a week to choose a case. Some ideas come unsolicited from MGH doctors, and Rosenberg occasionally requests suggestions based on a hot topic—such as the first patient admitted with H1N1 influenza in 2009. Exploring new territory in that way can be particularly valuable, and in 2020, 10 Case Records focused on patients with COVID-19. “Amid the chaos of the early days of the pandemic, Case Records provided a powerful way to share our experiences,” says Rosenberg. Physicians from around the world presented COVID-19 cases at MGH’s virtual CPCs. In one of those, a transplant nephrologist from Italy related how he was managing immunocompromised organ-transplant patients who got COVID-19. “Italy was a few weeks ahead of Boston in dealing with COVID, and we learned critical information about the patients we were just beginning to see,” says Rosenberg.

The Case of Too Much Licorice

A man arrives at the emergency room after heart failure. Attention turns to his diet.

The 54-year-old collapsed in a fast-food restaurant, and it took a combination of injections, intravenous medications and electrical shocks to restart his heart. By the time he arrived at MGH, his heart rate was rapid and irregular, and his blood pressure was high.

Lab results showed a severe shortage of blood potassium, vital for proper heart functioning. The patient had no personal or family history of cardiac symptoms but had previously used heroin and had an untreated hepatitis C infection. Further tests, which ruled out other causes, led physicians to suspect that his low potassium levels were the result of a drug or food.

According to family members, the man subsisted on several bags of candy every day, and three weeks earlier had switched to licorice, an excess of which can cause heart problems.

As his organs shut down, the patient produced less and less urine, and his family declined further treatment. He died 32 hours after he arrived.

One of the most widely read Case Records, published in 2010, involved the surgeon who operated on the wrong site and did the wrong procedure—and who courageously presented the case himself. “That allowed us to bring up the topic of physician errors, a topic Cabot had raised in the earliest days,” says Rosenberg. “This was a phenomenally skilled surgeon, and if he could make that kind of error, there’s a very good chance similar things are happening elsewhere.” After explaining what went wrong, the surgeon also described new safety protocols put in place after his error.

During a CPC, presenters take the audience through the steps—and missteps—they considered in arriving at the likely diagnosis and conclude by stating what they think is wrong with the patient, as well as the test or procedure they would use to confirm the diagnosis. The pathologist who interpreted the patient’s biopsy or the radiologist who read the definitive MRI or CT scan then gives the real diagnosis.

In one rare instance, there was no diagnosis.

In one rare instance, there was no diagnosis. MGH hematologist David Sykes presented a patient with an unusual constellation of clinical conditions, including an excess of red blood cells and acute kidney failure. It was something he’d never seen before, and when the case was published online, Sykes asked readers to contact him if they had treated a similar patient. “Almost instantly, physicians from two other academic centers around the world responded with stories of patients just like the one David described,” says Rosenberg. Discussing their patients, the clinicians realized they had discovered a new and ultra-rare disease which they called the TEMPI syndrome. In the 10 years since the CPC was published, Sykes and colleagues have identified 34 people worldwide with TEMPI syndrome and have published several papers on its diagnosis and treatment.

Case Records continues to evolve. For the past five years, for instance, Rosenberg has run an online quiz called Case Challenge, inviting NEJM readers to make a diagnosis using the same patient information that an upcoming case will be based on. Readers get to choose from among six possible diagnoses, and once they enter their answer, they can see how other readers have voted. Then, a week later, they can read that record to find out whether they were right or to learn why they were wrong. “Thousands of readers participate,” says Rosenberg, who envisions other ways to make Case Records more multimedia and interactive, “especially for younger doctors who have never actually held a paper copy of NEJM.”

While the formats may change and the platforms shift, Rosenberg sees the Case Records serving a central mission in medical education, one that will always be needed. “The case method takes unusual and fascinating medical cases, and it cleverly uses those to teach fundamental diagnostic and management skills,” he says. “Someone once told me that medical school teaches you to think like a scientist,” adds Harris, “but Case Records teaches you to think like a doctor.”

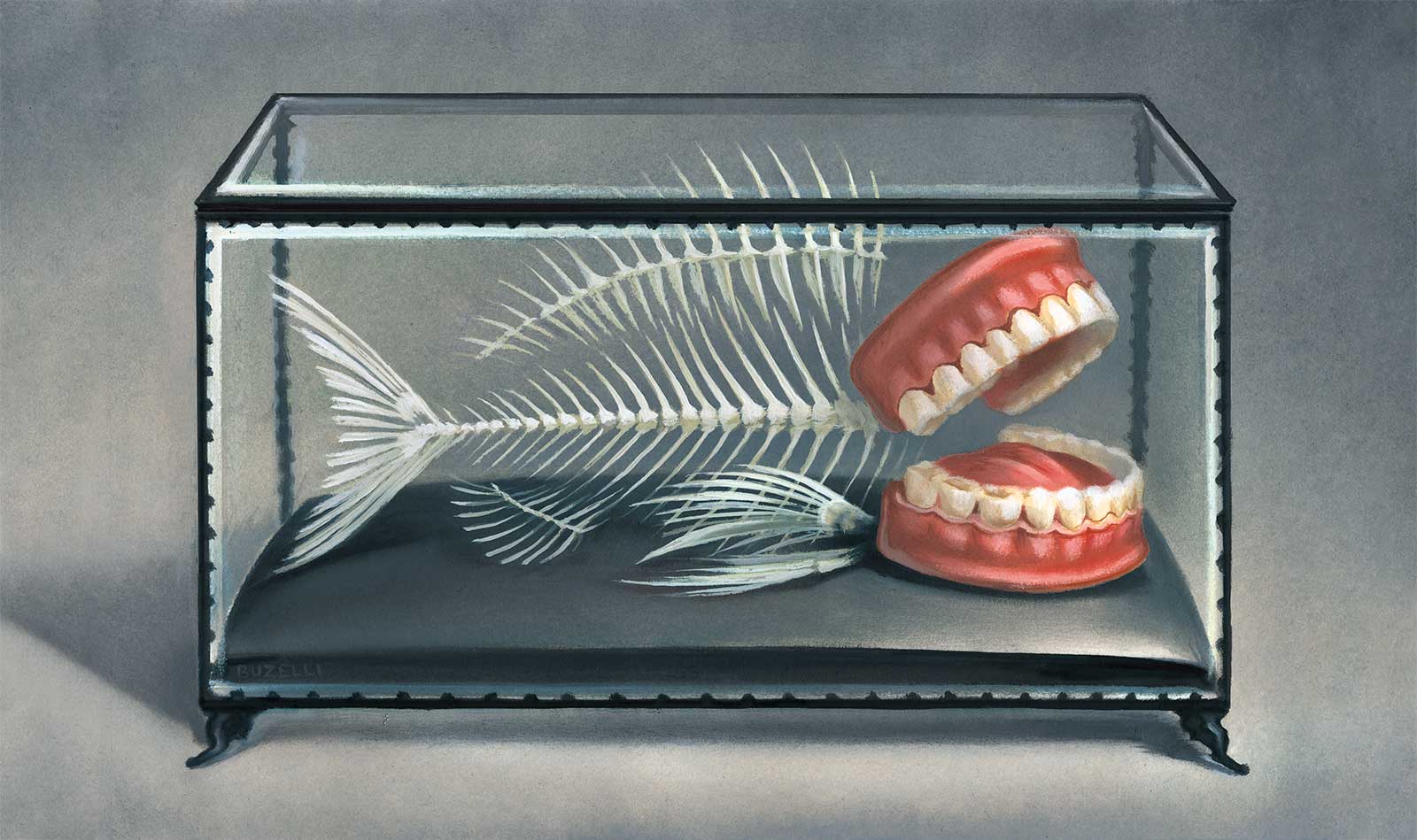

The Case of the Villainous Fish Bone Symptoms compatible with infectious disease turn out to be the result of a meal gone wrong.A 37-year-old New England expat, living in Vietnam, had experienced “rolling spasms” in his chest and, later, fevers, chills and body aches. Tests were negative for dengue, malaria, HIV and other diseases; an ultrasound showed a slightly enlarged liver and spleen. Further tests revealed bacteria in the blood and a CT scan showed possible lesions in the liver. A consulting MGH physician suspected a liver abscess—and the mortality rate for those may be as high as 12%. He urged transfer to MGH, where CT images revealed a “hyperdense” foreign body in the pancreas—a fish bone. Reaching the bone risked damaging vital organs, but a surgeon managed to get in, cut the bone in two and safely extract both pieces.

Dossier

“SARS-CoV-2: The Pandemic of Covid-19,” Case Records of the Massachusetts General Hospital, May-September 2020, editors Eric S. Rosenberg and David N. Louis. The book is a collection of case studies of 10 COVID-19 patients with a range of ages and other illnesses. All of the cases were published in The New England Journal of Medicine and hold lessons about treating a novel illness.

Keen Minds to Explore the Dark Continents of Disease, edited by David N. Louis and Robert H. Young, January 2011. This history of pathology at Massachusetts General Hospital devotes a chapter to the origin and development of Case Records, which have played a role in educating both young doctors and the wider profession.

Stay on the frontiers of medicine