Published On September 18, 2021

In September 2021, Massachusetts General Hospital marks the 200-year anniversary of its first admitted patient. Proto commemorates that event with special print issue, which you can download here.

A modern case of syphilis ends with a quick shot, but that treatment came only after centuries of discovery. The disease first tore through Europe in the 15th century, and from the very beginning it pushed forward each new era of medicine. Its modern name came from a poem by Girolamo Fracastoro, a 16th-century Italian whose work on syphilis helped establish one of medicine’s most important ideas—that germs, not bad air (“miasma”), could cause disease.

One reason syphilis drove so many advances was the misery it caused. The very first patient to be treated in the Bulfinch Building was a 30-year-old saddler with syphilis. The disease had caused ulcerations in his nasal canal and “several portions of bones were discharg’d through the mouth and nose,” according to the medical record. The only treatment his physicians could offer was mercury salts, which caused constant diarrhea and “gripping pain in the bowels.”

In the 20th century, many investigations finally bore fruit. The parasitic bacterium that causes syphilis, Treponema pallidum, was discovered in 1905, the Wassermann blood test for syphilis became available the following year, and in 1910, the arsenic-based treatment Salvarsan was introduced. Salvarsan was the first “magic bullet” cure in medicine and the world’s first blockbuster drug.

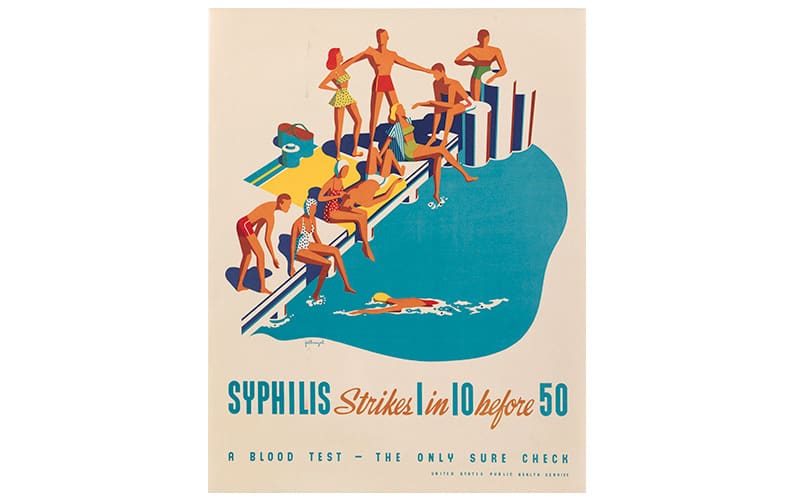

Source: Lithograph After Fellinagel, 1940/Wellcome Collection.

This poster from the U.S. Public Health Service was printed in the 1940s, well after the first cures for syphilis had been found and administered.

Into this context came the extraordinary physician William Augustus Hinton. The son of enslaved people, Hinton graduated from Harvard College in 1905 and got his medical degree, with honors, from Harvard Medical School in 1912. He was the first Black physician at Massachusetts General Hospital, and, while he was not allowed to practice medicine, for three years he worked as a volunteer assistant in the Pathology Department, performing autopsies on patients who died of suspected syphilis. He used what he learned to develop the Hinton test for syphilis, which became the standard diagnostic test used worldwide. Hinton’s Syphilis and Its Treatment, published in 1936, was the first medical textbook authored by a Black person.

Throughout his education and career, Hinton was determined to succeed on the merit of his work alone. He refused scholarships reserved for Black students and declined the 1938 NAACP Springarn Medal out of concern that his research would not be taken seriously if other scientists realized he was Black. For the same reason, he stayed away from medical conferences.

Source: Courtesy Tufts Medical Center.

William A. Hinton took pains not to disclose his race in journal articles, worried that readers might unjustly question his research.

After more than 30 years of serving on the faculty and just a year before retiring, he finally became a tenured professor—Clinical Professor of Bacteriology and Immunology—in 1949. “Dr. Hinton was the first African American professor, not just at HMS, but at Harvard University,” said Edward Hundert, HMS Dean for Medical Education, in a recent statement. “His public health and biomedical advances in the diagnosis of syphilis helped untold numbers of patients, and his writing on the role that socioeconomic factors play in health outcomes make him as relevant today as when he wrote those works almost a century ago.”

After World War II, physicians at the MGH believed that the introduction of penicillin and other microbial agents would eliminate infectious diseases forever. But they failed to take into account that human sexual behavior hasn’t changed in centuries, and today, MGH treats plenty of patients with sexually transmitted infections in its Division of Infectious Diseases—which has offices in the Bulfinch Building.

Stay on the frontiers of medicine

Related Stories

- The Atom and the Adam’s Apple

The use of energy waves in medicine leapt forward with the contributions of two Bulfinch pioneers.