Published On August 11, 2022

In the earliest months of the COVID-19 pandemic, a sense of mission carried Molly Phelps through the days. As an emergency room physician on the front lines, she was able to remind herself that this was the work she’d signed up for. “I knew there was a real chance I might die,” Phelps says. When reports surfaced of physician fatalities in China and Italy, she and her husband prepared a new will to make sure their two children would be taken care of. Then she put on her gear and went to work.

Yet during the many months that followed, as one COVID wave after another rose and crested, Phelps began to wonder how long she could keep at it. The safety challenges didn’t go away, working conditions continued to be grueling and there was a constant struggle to get supplies and support. As culture wars over COVID vaccination and treatments grew, clinicians found themselves facing the ire of patients taken in by rampant disinformation. Anxiety and exhaustion wore her down, she was barely eating or sleeping and she had a hard time containing her anger at patients who chose not to be vaccinated. “I didn’t want to give the last bit of me to unvaccinated people,” she says. Finally, after nearly two decades in the ER, Phelps worked her last shift in September 2021. “I will never return to emergency medicine,” she says.

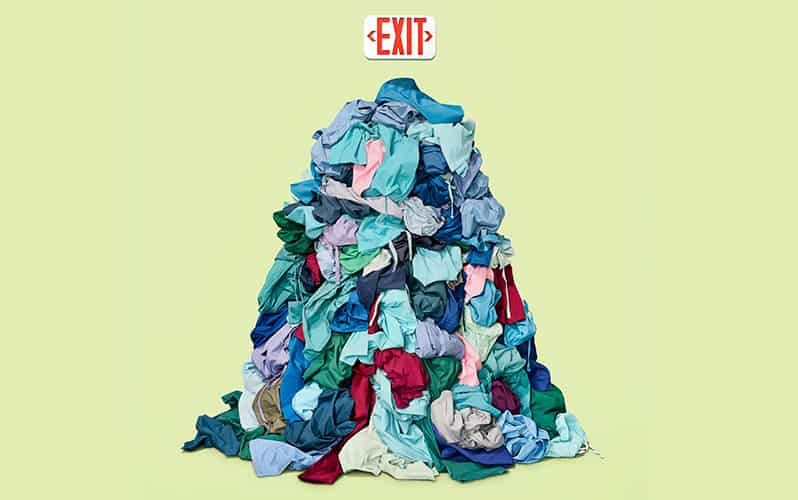

Stories like hers are dishearteningly common. The “great resignation” has ravaged health care as physicians and nurses give up their posts at hospitals, nursing homes and medical practices. Nonclinical positions are also going empty, with housekeeping workers, security guards, administrative managers and C-suite executives heading for the door faster than their replacements can be found. Since May 2021, nearly 70 million American workers have left their jobs, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. The rate of departures shows no sign of abating.

As the nation’s largest employer, the health care sector has been particularly hard hit. A recent survey found that almost one in five health workers has resigned since the pandemic’s start, and nurses are departing at a rate of nearly one in three. Those who don’t retire are taking other jobs, often outside of nursing, that offer better pay, greater flexibility and less stress. Among those who have stayed on, more than a third say they may leave by the end of 2022.

“The U.S. health care workforce is in peril,” says Christine Sinsky, a physician who serves as vice president of professional satisfaction at the American Medical Association. “If even half of nurses and physicians who say they want to leave go through with their plans, we won’t have enough staff.”

With patient volumes expected to rebound to above pre-pandemic levels, and as seemingly endless waves of COVID continue to fill emergency rooms and hospital beds, facilities across the country are searching for ways to persuade workers to stay even as they scramble to hire replacements for those who don’t. Pressure is rising for industry leaders to provide solutions. “Ask any hospital chief executive and you’ll hear that bolstering the workforce is priority one, two and three,” says Akin Demehin, senior director of policy at the American Hospital Association. How to do that is still not clear.

Burnout was a problem for physicians and nurses long before the pandemic, and resignations and retirements had already been increasing. The health care workforce itself is aging just as almost 70 million baby boomers in their 60s and 70s have been fueling an exploding demand for care. In 2019, the country had 20,000 fewer physicians than it needed, according to the Association of American Medical Colleges, and in a 2021 update, the group estimated that the shortage could rise to 124,000 physicians by 2034. There aren’t enough nurses, either. Gerard Brogan, director of nursing practice at National Nurses United, the nation’s largest nurses’ union, cites a lack of jobs that offer competitive pay, union protection and safe and healthy workplaces.

Long hours, hostile patients and safety concerns aren’t the only factors driving the exodus. Many in health care are also worn down by the emotional toll of losing patients in devastatingly high numbers. In a June-September 2020 survey, health care workers reported that providing care during the pandemic had increased stress (93% of those surveyed), anxiety (86%), frustration (77%) and exhaustion and burnout (76%), and three out of four said they felt overwhelmed by what they’d lived through. Since that survey, rates of depression, insomnia and post-traumatic stress disorder have soared.

In addition to the stress, many are having second thoughts about the dangers of COVID infection on the job. One analysis found that more than 3,600 U.S. workers in the industry perished during the pandemic’s first year, and one in three of those who died were nurses. Last winter’s omicron virus variant was particularly deadly for health workers, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Long hours, hostile patients and safety concerns aren’t the only factors driving the exodus.

While the burnout crisis predated the pandemic, the past year has been the final straw for many workers. U.S. hospitals have lost more than 75,000 employees since the pandemic’s start, and in March 2022, nearly a quarter of those institutions reported a critical staffing shortage. A few months earlier, during the omicron surge, 30% of reporting hospitals were struggling to find the bare minimum of clinicians and support personnel to keep the doors open. Spiraling labor costs, which make up more than half of health system budgets, have left fully a third of hospitals operating in the red, with rural hospitals most at risk of financial peril. “Workforce shortages forced many rural facilities to double what they were paying employees before the pandemic,” says Alan Morgan, chief executive officer of the National Rural Health Association. Federal pandemic funding helped cover those higher costs, but with that money now running out, more than 20% of rural hospitals are at risk of closing.

The size of the problem makes finding solutions daunting. In the month of April 2020 alone, for instance, the rate of attrition for physicians leaving their practice was nearly four times what it was April 2019, which amounted to a loss of several thousand doctors. If current trends continue, health care could have a shortfall of 3.2 million lower-wage workers by 2026, including medical assistants and home health aides, according to a report from HR consultant Mercer.

Gail Gazelle, assistant professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School and a Master Certified physician coach, believes the problem may even be accelerating. “There’s a domino effect,” Gazelle says. “Understaffing is causing more people to leave because their situations are becoming untenable in terms of patient safety and their responsibilities as clinicians.” In one survey, four out of five health care workers said they had felt the effects of the national labor shortage. They cited not only their increasing workloads but also the rushed or substandard patient care that resulted from a lack of personnel.

“With so many nurses retiring or moving on during the past two years, we’re being asked to take care of more patients, and we often find ourselves working with less experienced team members,” says Beth Wathen, a critical care nurse and the 2021-22 president of the American Association of Critical-Care Nurses. A recent AACN survey found that nine out of 10 nurses said their careers would be shorter than intended because of the new staffing pressures. “The overwhelming fear is that this is the new normal,” Wathen says.

Finding new workers to bolster the workforce is the clear solution, but amid the exodus, most hospitals and other health care organizations can hire only staff that are expensive and temporary. The average pay for “travel” nurses, who fill in wherever they’re needed, is now more than twice what it was before the pandemic, according to the AHA, and another survey found that roving “locum tenens” physicians can earn up to 30% more than permanent staff doctors.

In 2020, demand for travel nurses grew by more than a third, and it is expected to expand an additional 40% in the near future, according to one analysis. High salaries are motivating some on staff to quit and become travel nurses, who now account for at least 2% of the nursing workforce. “ICU nurses who choose to stay may find themselves working with a travel nurse making three to four times what they earn,” says Wathen.

Some physicians, too, are shifting to contract work. Rohit Uppal, a physician and chief clinical officer of TeamHealth Hospitalist Services in Knoxville, Tennessee, says the firm now has more than 3,000 hospitalists working in more than 200 health care systems around the country. The company had a banner recruiting year in 2021, Uppal says. “Physicians are stressed out and don’t feel valued,” he says.

Roni Devlin, an infectious disease physician, gave notice at her job at a community-based teaching hospital just weeks before the start of the pandemic. “Being a doctor had always been stressful, but it had become more burdensome throughout the years,” Devlin says. For the past two and a half years, she has worked as a locum tenens physician on several out-of-state assignments that allow her to return to her Midwestern home at least twice a month. Working at temporary jobs has given her relief from full-time administrative burdens and helped her recover from the exhaustive symptoms of burnout. Still, giving up job security and the benefits of her staff position, as well as having to take time away from her family, required consideration.“I might still retire early,” she says.

Any solutions to today’s staffing crisis will also have to finally address the crisis of mental health. The physicians that Gail Gazelle coaches are “exhausted, emotionally drained, cynical and feel like cogs in a wheel,” she says. Even now, with stress levels running high, only 13% of American doctors have sought treatment to address mental health concerns. Many worry about the stigma of seeking help, which means it will be up to institutions not only to normalize avenues for relief, but to create less stressful work environments.

Indeed, research from the National Academy of Medicine suggests that most factors fueling burnout and resignations are beyond the control of clinicians. While health care has long depended on the resilience and dedication of its workers, that reliance on personal responsibility is past the breaking point. “We have to focus on fixing the workplace rather than the worker,” says the AMA’s Christine Sinsky.

To that end, Sinsky and physician Heather Farley, chief wellness officer at ChristianaCare in Delaware, among other experts, helped create the 2022 Healthcare Workforce Rescue Package. It includes evidence-based strategies that health care systems can adopt right away as a foundation for longer-term solutions. Those include peer-support programs, crisis documentation protocols and better staffing and workflow tools, all of which can help ease clinicians’ burdens while enabling them to recognize when they or their colleagues are nearing their limits.

Chief among the recommendations is to put an executive leader in charge of implementing wellness programs. Indeed, “chief wellness officer” has become an in-demand job posting. Farley’s own appointment as CWO of ChristianaCare preceded the pandemic, and many initiatives she and her staff implemented—wellness resources, peer support and a mental health hotline, among other changes—proved effective when stress levels escalated.

Luminis Health Doctors Community Medical Center in Maryland has also taken steps to expand its wellness culture, says Deneen Richmond, president of the hospital. In one seemingly minor effort, Richmond and her team now walk the halls several times a week with an “exhale cart” stocked with snacks and other comfort items. There’s also an “exhale room” with coloring books and massage chairs. “This is less about giving someone a bag of crackers than about connecting with people,” Richmond says. “Just from casual chats in the hallway I’ve learned so much about the obstacles making it hard for our people to do their jobs.”

Amping up pay and benefits also helps. This year, Luminis implemented a $29 million program for its 6,700 employees that includes tuition assistance and loan repayment programs, a $17 minimum wage for hourly workers and bonuses for nurses and others in high-demand, high-vacancy positions. “We did a full compensation review,” Richmond says. Increasing what existing employees earned made more sense than paying exorbitant rates for temporary workers, she says.

Yet as departures continue, many hospitals and health care systems are necessarily focused on hiring. Northwell Health, New York state’s largest health care provider and private employer with 80,000 workers, currently has about 5,000 vacancies. It has sent recruiting teams to places of worship, malls and job fairs, and uses social media videos to attract qualified candidates. “We’re doing anything and everything to market ourselves,” says Maxine Carrington, Northwell senior vice president and chief human resources officer, who estimates that the health care system interviews about 4,000 job candidates a month.

“It’s an extremely competitive hiring environment,” says Carrington, who notes that the organization has had to increase starting salaries and benefits to meet market conditions. But Northwell has also added perks to help retain current employees, increased investment in professional development and instituted new programs for employees overwhelmed by the stress of patient care in one of the nation’s epicenters of COVID infection. In 2021, Northwell opened its Center for Traumatic Stress, Resilience and Recovery, which provides coaching, grief counseling, a 24/7 hotline and other features to clinicians, support workers and their families.

One program, Northwell Celebrates, is designed to show Northwell’s appreciation for its workforce. “We wanted to push gratitude,” Carrington says. Frontline workers got a $2,500 bonus in 2020 and an extra week off. There are gift boxes, free appointments at a mobile on-site spa, prepared meals delivered to workers’ homes and family movie and concert nights.

The government also has a part to play in reducing medicine’s unsustainably high attrition rates. In a March 2022 letter to Congress, the AHA called health care’s workforce shortage a “national emergency” requiring immediate action. The hospital group called for increased funding for workers’ mental health needs as well as a number of moves that would ease the personnel gap—including lifting the cap on Medicare-funded physician residencies, increasing funding for nursing schools and fast-tracking visas for international health workers.

In January 2022 the Biden-Harris administration allocated $103 million in American Rescue Plan funds to establish evidence-based programs promoting the mental health and well-being of health workers. In addition, the Dr. Lorna Breen Health Care Provider Protection Act, which became law in March 2022 and is named for an emergency department physician who took her own life early in the pandemic, provides up to $135 million over three years to train providers about suicide prevention and behavioral health.

Other federal legislation is designed to combat burnout and increase the supply of new clinicians and other health workers, and states are relaxing licensing requirements and expanding training programs and compensation, according to the National Academy for State Health Policy. Last January, Pennsylvania appropriated $225 million to fund retention and recruitment payments for health workers, and in April, New York announced a $20 billion plan to pay higher wages and bonuses for frontline health workers as well as home care workers.

The government has a part to play in reducing medicine’s unsustainably high attrition rates.

As they wait for such efforts to bear fruit, some nurses and others in health care are doing what they can to improve their lives at work. Nerissa Black left a corporate career to become a nurse, and she loves what she does. Yet during the winter COVID surge in early 2021, the California telemetry nurse found herself overwhelmed after her state lifted a cap on the ratio of patients to nurses. She had just 10 minutes an hour to check on the severely sick patients under her care, and that was barely enough time to switch in and out of protective gear between patients. “The trauma of those three months was horrific,” she says.

Black began seeing a therapist and taking medication for anxiety. “There was no peer support at the hospital; you had to seek help on your own,” she says. Yet by the end of last summer, amid continuing staff shortfalls and looking ahead to other anticipated COVID surges, she considered exiting nursing altogether. “I thought, ‘I can’t go through this again.’”

Months later, she found a nursing position in a gastroenterology lab at her hospital, where she attends to patients undergoing procedures. “It’s not as all-consuming as being at the bedside of acutely ill patients,” Black says.

But job changes like hers, even when clinicians and others stay with the same employer, do little to relieve the pressures of the great resignation. Black’s hospital continues to deal with a nursing shortage, she says, and it has struggled to fill open positions in the department she left. “Morale is really low,” she says.

Dossier

Allinforhealthcare.org.This online hub sponsored by a coalition of health care organizations contains action steps, practical tips and resources to support organizations looking to create programs for health care worker well-being.

“COVID-Related Stress and Work Intentions in a Sample of US Health Care Workers,” by Christine Sinsky et al., Mayo Clinic Proceedings, December 2021. The findings of this American Medical Association-sponsored study revealed a workforce intent not only on cutting back their hours but also on leaving their current jobs.

“The Evolving Role of the Chief Wellness Officer in the Management of Crises by Health Care Systems: Lessons from the COVID-19 Pandemic,” by Kirk Brower et al., NEJM Catalyst Innovations in Care Delivery, April 2021. The authors explore the role of the CWO at nine organizations in the midst of the pandemic.

Stay on the frontiers of medicine

Related Stories

- Clinician Violence Moves Online

As practice goes digital, so too does a brutal workplace hazard.

- When Healers Get Hurt

For nurses and doctors, abuse from patients is just part of the job. But as attacks mount, hospitals are trying to defuse the tension.

- Rage in the Streets

Are there echoes of the “cholera riots” in the age of COVID-19?