Published On May 3, 2009

IN 1926, OTTO NEURATH, the Austrian philosopher of science, christened the 1900s the “century of the eye”: “Wall posters call out to us from the streets and hallways; exhibitions are inviting us; millions of people are watching the motion picture screens every evening….”

For the health sciences, this development became a lifesaver. In a time before preventive medicine, the containment of infectious diseases depended on widespread awareness. To broadcast prevention strategies, public health agencies developed (in a modern phrase) multimedia campaigns consisting of radio advertising, pamphleteering and posters.

“Media technology was as much of a magic bullet as vaccines were,” argues Michael Sappol, the curator of “An Iconography of Contagion: An Exhibition of 20th-Century Health Posters From the Collection of the National Library of Medicine.” The show will travel to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention this September. With 22 posters from the United States and abroad, the show breaks ground by examining the art as well as the science of health campaigns, which employed modernist style to great effect.

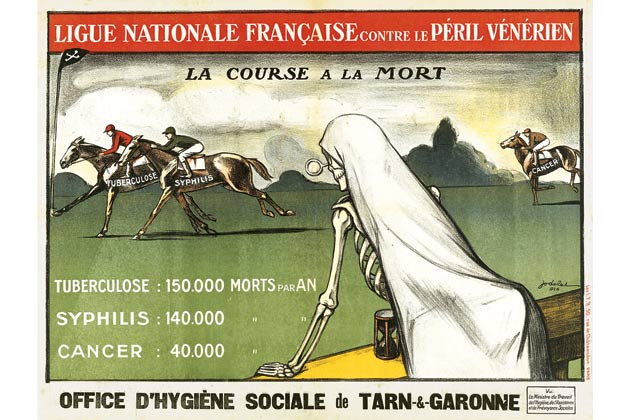

“La course à la mort,” by Charles Emmanuel Jodelet, the oldest work in the show, calls to mind nineteenth-century caricature. Death, personified as a hooded skeleton, watches a race between tuberculosis, syphilis and cancer. As is typical of the time, text, rather than image, communicates the essential information; in this case, the annual death rates in France from the three diseases. The lesson is that the two contagious diseases lead the pack—and the public should avoid them.

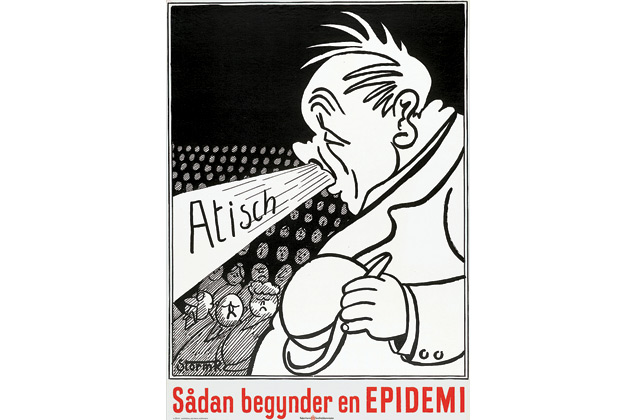

Following perhaps a decade later, “Atisch” (Achoo) sounds a clear call to action in a more abstract way. Inspired by the flatness and the economy of line seen in Art Nouveau and Art Deco, Danish cartoonist Storm P shows a man sneezing on a disapproving crowd. The figure and the caption—“Thus begins an epidemic”—are easily grasped from a distance.

Another decade, another style: “She may be.. a bag of TROUBLE” recalls the style of pulp novels and pinups. “Posters about VD were meant to incite anxiety and also give pleasure,” says Sappol. This one, targeted at GIs in Europe, was intended to reduce the spread of syphilis and gonorrhea. [See top image.]

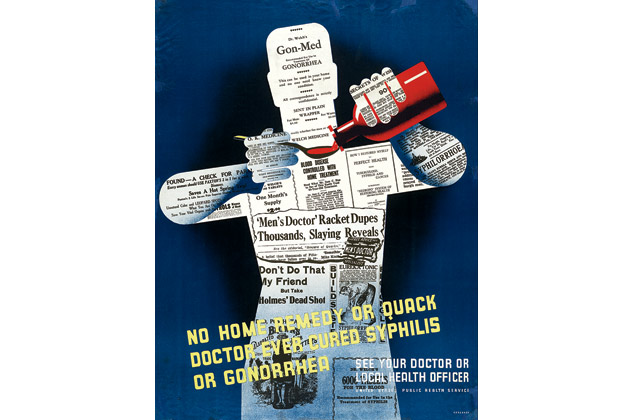

The exhibit’s most innovative image, “No home remedy or quack doctor ever cured syphilis or gonorrhea,” by Leonard Karsakov, takes its cue from Russian constructivist art, merging images and text, and Dada collage to form a patient made up of newspaper advertisements for fraudulent remedies. The patient has literally ingested bad advice.

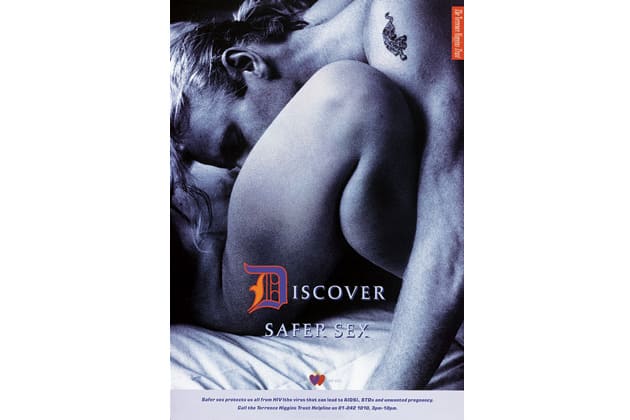

After the Second World War, as health services focused more on preventive science than public awareness, came a downturn. Then the rise of a plague no science could prevent—AIDS—led to a rebirth. “Discover safer sex” uses the image of a sexually ambiguous couple to shock and intrigue. Nuance and artistry may have been lost, but 100 years on, the arts continue to play a role in the fight against infectious illness.

All posters courtesy of the National Library of Medicine

Stay on the frontiers of medicine