Published On May 3, 2008

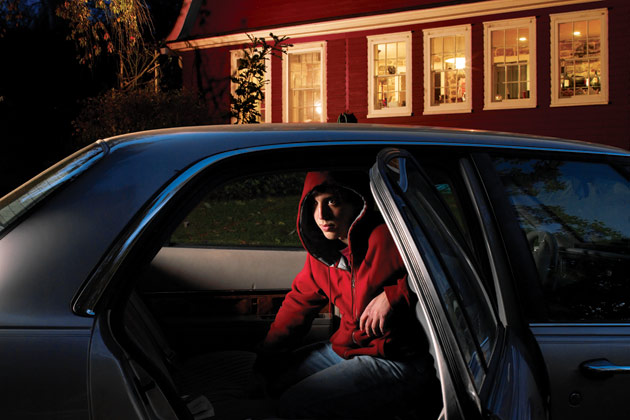

A YOUNG MAN WE’LL CALL JOHN had been hospitalized multiple times for acute anxiety and depression when he began hearing voices and seeing violent images. The 19-year-old rarely left his parents’ home in a Portland, Me., suburb, and he had threatened suicide. Yet, desperate as his situation seemed, it was hardly unique. Each year thousands of adolescents and young adults are struck by similar symptoms that frequently, perhaps one time in three, prove to be the precursors to full-blown schizophrenia, a grim diagnosis of delusions and paranoia.

More often, though, schizophrenia doesn’t develop, so doctors have tended to proceed cautiously as they try to determine exactly what is troubling these young people. But William McFarlane, a psychiatrist at Maine Medical Center in Portland and director of a mental health program called Portland Identification and Early Referral (PIER), doesn’t wait. In John’s case, McFarlane and his staff moved to block John’s anticipated psychotic illness with a mix of medication and family counseling that helps patients cope with stressful situations at school and work. Two years later, John is living on his own for the first time, holding down a job at a Goodwill store and hoping someday to go to college. “They helped me control my emotions and deal with the images in my head,” he says. “I can go about my life now in a way that I couldn’t before.”

McFarlane thinks that, at least some of the time, schizophrenia can be headed off—and that measured against the undoubted perils of the disease, early action is justified. A condition that may account for as many as 25% of the suicides among young people in the United States, schizophrenia is notoriously difficult to treat. As patients begin to lose touch with reality, they tend to withdraw, putting themselves far beyond the reach of those who might help them. But studies show that one to two years typically pass between the onset of symptoms and the first psychotic breakdown, and McFarlane’s approach is to act decisively during this precursory, or prodromal, phase. Other scientists also advocate aggressive treatment during the prodrome, though McFarlane is more willing than most to take the controversial step of prescribing antipsychotic drugs to patients with severe symptoms who may or may not ultimately develop schizophrenia.

The potential benefit of keeping schizophrenia at bay, perhaps permanently, is huge, and McFarlane’s methods are now getting a much broader test. His research program has expanded from Portland to small cities in California, Michigan, New York and Oregon, and depending on the study’s conclusions, McFarlane’s methods could one day contribute to routine clinical practice. Meanwhile, other research is rushing ahead in the United States and elsewhere.

HARRY STACK SULLIVAN, THE AMERICAN PSYCHIATRIST best known for his theories of how interpersonal relationships fuel mental illness, wrote in a 1927 letter to a colleague that “incipient” cases of schizophrenia “might be arrested before the efficient contact with reality is completely suspended.” Yet during Sullivan’s era, and for decades afterward, the mainstream view was that schizophrenia “doomed patients from the womb,” says Jeffrey Lieberman, chair of psychiatry at Columbia University’s College of Physicians and Surgeons.

It wasn’t until the 1980s that research began to suggest otherwise. It appeared that if patients were treated with drugs and talk therapy soon after their first psychotic break—the point at which they had lost the ability to recognize that their hallucinations and delusions weren’t real—there was a decent chance they’d recover. Those who got quick attention had symptoms that were less frequent and less intense, and there was less evidence of brain damage. “Until then, there wasn’t any real rush to treat,” says Lieberman. “But we recognized that the faster the patients were treated, the better.” Eventually that focus shifted to an even earlier stage, when outright prevention might be possible.

The consensus today is that prodromal symptoms typically emerge during the teen and early adult years. Preliminary imaging studies show that brain changes associated with schizophrenia follow a steady progression and likely involve an increasing loss of synapses between individual nerve cells, particularly in the frontal lobes, where language, memory, socialization and other behaviors are coordinated. Additional preliminary imaging studies also show steady declines in gray matter, spreading out from the frontal lobes as patients shift from prodromal states toward more definitive disease.

When the number of synapses dwindles, prodromal patients begin losing powers of judgment and reason and may feel overwhelmed as they’re deluged with unprocessed sensory stimulation. Hallucinations and delusions ensue—slowly at first, but gaining in intensity until a psychotic break occurs. Like others at this stage, John experienced moments when he would hear or see things that weren’t there. But unlike truly psychotic patients, who think their hallucinations are real, he could still be convinced that he was, in fact, hallucinating. That capacity to distinguish hallucinations from reality is what sets the prodrome apart from psychotic disease.

The prodromal stage may last from several weeks to several years, and some patients may never develop schizophrenia. Thus, one of the first challenges of prodromal treatment is to identify the most vulnerable patients. In recent years, Alison Yung and Patrick McGorry, both professors at the University of Melbourne in Australia, described three features that can put patients at high risk for schizophrenia: unusual perceptions or beliefs that patients don’t yet hold in rigid ways, such as paranoid thoughts that they’re being followed or watched by others; a family history of schizophrenia; and a tendency to experience fleeting hallucinations and delusions that they can still distinguish from reality.

The Australian scientists produced a detailed diagnostic questionnaire that Thomas McGlashan, a professor of psychiatry at the Yale University School of Medicine, modified for research settings. McGlashan’s “structured interview for prodromal syndromes,” or SIPS, has become a standard diagnostic tool in the United States and in some European countries. Patients who undergo a SIPS evaluation might be asked whether a voice they hear is real or “just in their head.” They might also be asked whether anyone else can hear the voice. A patient’s answers enable clinicians to characterize prodromal symptoms and their severity and decide what to do, if anything.

BY MAKING IT POSSIBLE TO IDENTIFY vulnerable patients consistently, the SIPS evaluation helped fuel a dramatic expansion in prodromal research. There are prodromal studies at more than 30 research sites worldwide. Robert Heinssen, associate director for prevention research at the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), heads the North American Prodrome Longitudinal Study, a collaboration of eight independent research projects with a total of more than 850 subjects. McFarlane’s program, launched in 2000, is now among the largest schizophrenia prevention efforts in the United States. PIER counsels teachers, clinicians, social workers and others who interact with young people on how to recognize prodromal warning signs: sudden declines in performance at school, social withdrawal, poor hygiene and trouble concentrating, among others. Patients receive two to four years of family counseling designed to build specialized coping skills and reduce stress. They also receive focused guidance at school or work and medications that often include antipsychotic drugs. “Most of our kids keep getting better,” McFarlane asserts. “Our experience has been that after a couple of years, they don’t need a lot more help.” McFarlane predicts that most patients will be able to come off medication, but he can’t yet say just when.

Other programs have similarly positive outcomes. Still, Barbara Cornblatt, a professor of psychiatry at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine in New York City, cautions that this approach is not ready for routine use. “We don’t know enough yet about appropriate treatment,” she says. “It may turn out that antipsychotics are useful only in combination with psychosocial approaches, or that we don’t have to use those drugs at all. If we do use them, we have to figure out when and for how long.”

WHETHER TO PRESCRIBE ANTIPSYCHOTICS is the burning question in prodromal treatment. The drugs’ side effects, including weight gain and heightened risk of diabetes, can themselves pose dangers to a patient’s health. Antipsychotics may also interfere with normal development of the adolescent brain, and McFarlane’s willingness to use them disturbs many scientists, though he insists that when side effects are observed, the PIER physicians immediately change the drug regimen. What’s more, the SIPS questionnaire, though sophisticated, is hardly foolproof, and there’s no blood test that predicts psychosis. Physicians must base a diagnosis on sometimes vague behavioral symptoms and subjective responses to questions, and part of the time they’re going to be wrong.

How many prodromal patients will in fact become psychotic? McFarlane thinks about a third will “convert” in the year after they’ve been identified. A recent NIMH study, published in the Archives of General Psychiatry on Jan. 7, 2008, found prodromal behaviors could predict psychosis correctly from 35% to as much as 80% of the time in high-risk youth, depending on the number of symptoms and their intensity. Those odds are high enough to justify treatment, McFarlane says. But conversion estimates gathered at individual program sites vary widely, with some as low as 20%. If the real conversion number is just one or two in five, suggests Diana Perkins, a professor of psychiatry at the University of North Carolina, prescribing antipsychotics may be too perilous, subjecting 60% to 80% of prodromal patients to medications without known benefits.

Only one study has investigated whether psychosocial interventions without drugs might effectively treat prodromal patients. Anthony Morrison, a professor of clinical psychology at the University of Manchester in England, found that giving high-risk patients cognitive behavior therapy (CBT) for as long as six months reduced the likelihood of psychosis by more than 90%. Morrison published his findings in the British Journal of Psychiatry in 2004; however, his study was limited to 58 patients, and their average age was 22. Younger patients diagnosed as prodromal tend to have much more severe symptoms.

There is also just a single study, published in 2006 by McGlashan and his colleagues at Yale and other centers, that has investigated antipsychotic medication as the sole therapy. The findings suggested that a drug called olanzapine could cut prodromal patients’ conversion rates in half. But those results are considered inconclusive because such side effects as weight gain and fatigue led to a high dropout rate in the treatment group, resulting in a less-than-optimal sample size.

In another study, published in 2002, the University of Melbourne’s McGorry reported that a combination of medication plus CBT was more effective at preventing schizophrenia than psychotherapy alone, though several of the patients in the study later became psychotic. McGorry would like to see further clinical research, and he’s currently conducting a randomized clinical trial that compares CBT with an antipsychotic drug called risperidone.

McFarlane, meanwhile, points out that although PIER’s patients aren’t yet psychotic, most come to the clinic in severe psychiatric distress, and when PIER provides comprehensive treatment, their symptoms generally improve. He says that among the patients, it is mostly those who have refused or stopped treatment who have gone on to suffer psychosis.

McFarlane says PIER’s not-yet-published data indicates that the program’s combination of medication and psychosocial support cuts patients’ risk of psychosis roughly in half. And PIER, which now uses a drug called aripiprazole that may pose fewer metabolic risks than other medications, is not testing how much that success depends on the drugs. Most of the team’s effort is devoted to reducing stress and improving the young person’s academic or work performance, saving medication only for those with more severe symptoms. “The risks of not using any medication are too high,” says McFarlane. “We might be consigning half the people in the trial to mental illness.”

IN THE FUTURE, PHYSICIANS MAY BE ABLE to identify physical signs, or biomarkers, indicating whether a particular patient is likely to develop schizophrenia. Some research is looking at brain-imaging data and gene-based biomarkers, says Tyrone Cannon, a professor of psychology and psychiatry at UCLA. In tracking brain changes leading from prepsychotic stages to schizophrenia, Cannon and his colleagues are testing the theory that prodromal symptoms appear as the adolescent brain “prunes” synapses, a process known as plasticity.

Just as removing a tree’s weaker branches allows its other branches to flourish, synaptic pruning strengthens needed connections while ridding the brain of those it no longer requires. But Cannon thinks this process goes haywire in the prodromal brain—that instead of eliminating synapses selectively, the brain hacks away at them indiscriminately or overaggressively. Better knowledge of that process and its genetic underpinnings may one day yield a range of diagnostic enhancements, he says. By combining biomarkers with the SIPS evaluation and other tools, clinicians might be able to reduce the number of patients mistakenly diagnosed as prodromal. Better knowledge of schizophrenia’s biological roots might also lead to improved drugs for treating it, such as compounds that protect brain synapses and plasticity.

“There have been phenomenal advances in understanding schizophrenia in the past decade, but we’re no closer to a cure than we were 30 years ago,” says the NIMH’s Heinssen. “So it’s exciting that if you catch schizophrenia during the prodromal phase, you might be able to keep it from progressing.”

Dossier

“Prediction of Psychosis in Youth at High Clinical Risk,” by Tyrone D. Cannon et al., Archives of General Psychiatry, January 2008. Involving 291 patients from research centers countrywide, this study was the largest to date to investigate the degree to which prodromal symptoms can predict schizophrenia—perhaps as often as 80% of the time.

“Prodromal Assessment With the Structured Interview for Prodromal Syndromes and the Scale of Prodromal Symptoms: Predictive Validity, Interrater Reliability, and Training to Reliability,” by Tandy J. Miller et al.,Schizophrenia Bulletin, Vol. 29, No. 4, 2003. Describes the origins of the key diagnostic tool for prodromal symptoms.

“Family Expressed Emotion Prior to Onset of Psychosis,” by W.R. McFarlane and W.L. Cook, Family Processes, June 2007. This study concludes that the heightened “expressed emotion”—criticism and anger—that families experience during a member’s prodromal phase is a reaction to, not a cause of, the member’s symptoms.

Stay on the frontiers of medicine