Published On January 27, 2020

AFTER HER RESIDENCY, JULIE Gunther took a standard position for a new family physician, signing on with a large medical system in southern Idaho where she stayed for five years. “My vision was to serve my community as a sort of Marcus Welby,” Gunther says, a nod to the compassionate and fictional family doctor who appeared on television in the late 1960s. But the reality was nothing like that. Administrative hassles were always front and center, and the few minutes she had with her patients were scarcely enough for her to get to know them. “I was always apologizing for being late,” she says. “I felt like my patients were being pushed through in an assembly line.”

More and more primary care physicians have the same complaint. Their offices are crowded with aging baby boomers and they’re besieged by paperwork and mushrooming requirements for preventive care, charged with improving patients’ health while also controlling costs. “We’re being asked to do more with fewer resources and less time,” says Bruce Landon, an internist at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston.

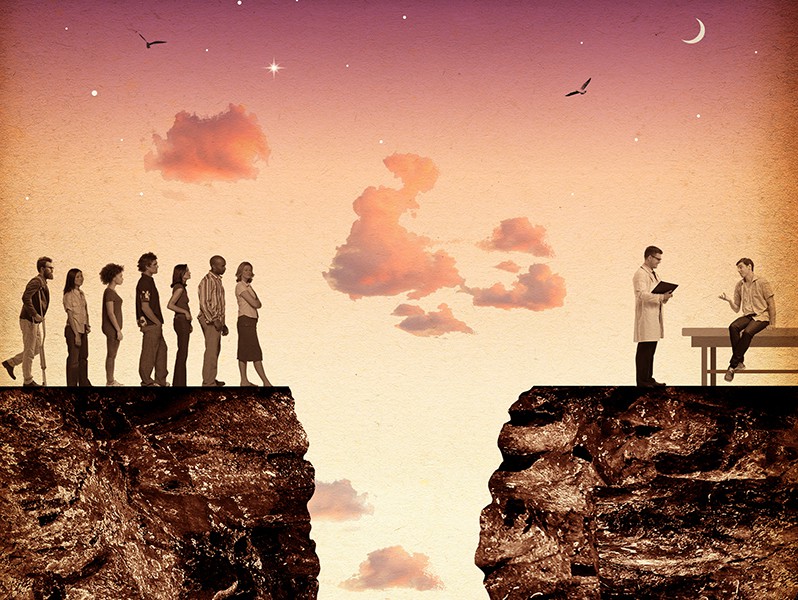

Fewer patients have a personal primary care physician—a recent survey showed that nearly half of those 18 to 29 years of age were going without—but most experts still believe that primary-care-centered medicine is worth preserving. Office appointments with an internist, family practitioner or pediatrician make up more than half of all patient encounters with doctors, and during these visits physicians diagnose and treat the vast majority of medical ailments and chronic diseases. These visits can keep small health problems from becoming big ones, says Joshua Metlay, chief of general internal medicine at Massachusetts General Hospital. “Primary care has been demonstrated to make a real difference in health outcomes,” he says.

Removing these providers from a patient’s life comes at a cost. The United States spends more per capita on health care than any other country, yet ranks 43rd in life expectancy—a discrepancy partly tied to a lack of preventive care, which in turn may be related to not seeing a generalist physician who conducts regular screenings.

The problem is not a new one, and rethinking the role of frontline physicians has led to decades of tinkering with alternative models. In recent years, physician burnout—an epidemic with a steep human cost—has given these efforts a special urgency. While outcomes of the first generation of experiments are rolling in, other innovative delivery models, many started by physician entrepreneurs, are beginning to upend notions about how, when and where primary care doctors see their patients.

These efforts, each very different, aim to re-engineer and strengthen primary care—and they call for a new level of investment, both from insurers and patients. “We’re in a moment in which the old model is collapsing,” says Alan Glaseroff, a family physician and professor at the Stanford Medicine Clinical Excellence Research Center in California. The new models will need to move quickly to take their place.

A LANDMARK 1978 REPORT from the Institute of Medicine defined primary care as “accessible, comprehensive, coordinated and continual,” to be placed in the hands of “accountable providers.” Yet the same report noted that the supply of physicians delivering primary care was and would continue to be inadequate. Then, as now, physicians-in-training were more likely to opt for narrower specialties that offered higher incomes, and only about one-third of the nation’s 700,000 practicing physicians today are primary care physicians. That percentage is likely to get slimmer. More than one in four primary care physicians is age 60 or older, and just about a fifth of medical graduates now choose primary care residencies—increasingly a pragmatic choice because starting salaries for primary care doctors don’t make much of a dent in the average medical student debt of $200,000.

The typical primary care physician now has a panel of 2,300 patients and must see 20 to 30 of them every day. The demand for their services seems to outweigh supply. More than an eighth of U.S. residents live in a county with a shortage of primary care physicians, and in some metropolitan areas, patients have to wait almost six months to see a doctor. When they finally do get in for a visit, they’re typically ushered out of the exam room in 15 minutes or fewer. Even after those 20 to 30 patients are gone, their physicians must spend hours updating electronic health records (EHRs) and other paperwork. Many physicians complain of feeling like they’re on a treadmill, losing the struggle to provide timely, high-quality care—and feeling the toll on their mental health. Every day, on average, a doctor commits suicide. “That’s basically a whole medical class’s worth of physicians that we’re losing every year,” Gunther says.

Efforts to rescue primary care have been sporadic and wide ranging. Many are built around or inspired by the “patient-centered medical home,” or PCMH. The “home” is figurative, referring to a team-based approach designed to help physicians navigate their patients through their “medical neighborhood” of specialists, hospitals, home health care and other services, and to connect them to appropriate community resources. It was developed by the American College of Physicians and promoted by the American Academy of Family Physicians and other physician groups as a way to treat the “whole patient.” For physicians, the team approach also considerably relieves the sole provider facing a mountain of patients and administrative tasks. The program has been adopted by many organizations, including Medicare and Medicaid, especially to manage the care of those with complex or chronic conditions. Fees paid by the government may be tied to performance metrics that measure quality, cost or patient engagement, and for insured patients, insurer costs can include additional monthly payments.

During the past decade, the PCMH has been widely tested by the federal government and states. One federal PCMH experiment, Comprehensive Primary Care Plus (CPC+), launched in 2017, aims to expand the reach of a promising earlier pilot. With almost 3,000 practices participating, CPC+ is the biggest, most ambitious reform effort yet for the federal Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services.

South Arkansas Medical Association Healthcare Services, a CPC+ participant, delivered traditional fee-for-service primary care until 2012, says Gary Bevill, a founding physician of the group. Now daily practice has changed from the ground up. Each physician is assigned to a team, or pod, that also includes nurses, care coordinators and care managers—people who can review patient charts before appointments, manage and check referrals and arrange transitions to other types of care. With that infrastructure in place, Bevill and other physicians can enter an exam room and focus solely on their patients. “I’ve already reviewed the EHR, so I don’t have to have my nose in a computer,” Bevill says. During four years in the earlier pilot, the practice not only saw big improvements in patient outcomes but also in employee and patient satisfaction.

About one in five primary care physicians currently practices in some variation of the PCMH. The Cleveland Clinic and the University of Colorado Health System have tested or implemented a version of the home model. Bellin Health in Green Bay, Wisconsin, has rolled it out over its entire system, which encompasses 140 primary care teams in 32 locations. During a five-year transition, teams using the model scored higher on most quality metrics. Patient engagement and staff satisfaction increased, and clinician satisfaction scores almost tripled. “Medicine isn’t an individual activity anymore, and for this to work, physicians have to work as leaders of a team,” says James Jerzak, the Bellin Health physician lead for team-based care, who helped implement the pilot. “Working as part of a team makes it fun to practice medicine again. It’s more satisfying for the staff and better for our patients, too.”

It was a rare case in which a better model for doctors and patients also meant a healthier bottom line. Improved efficiency has enabled doctors and other providers to see more patients, expanding access to primary care in the communities in which Bellin operates. And even though the health system hired additional staff, invested in training and technology and redesigned facilities, revenue also increased, with the team-based model credited for an average boost of $724 per patient yearly in some segments.

It’s not yet clear, however, whether larger-scale PCMH projects can actually both save money and improve care. Evaluations of federal efforts so far show modest improvements at best. Researchers concluded that the pilot that preceded CPC+ had no significant impact on physician burnout, Medicare spending or quality of care, although practices did report enhanced access and improved care management for high-risk patients. Gains from the first year of CPC+ also appear to be limited.

And instituting some version of the medical home carries a hefty price tag, costing practices in excess of $100,000 per physician per year, according to one study. During the pilot’s first two years, practices received median government subsidies of $115,000 per clinician in care management fees, and median care management fees for the newer CPC+ program have ranged from $88,000 to $195,000.

OTHER APPROACHES TO IMPROVE the lot of the primary care physician also rely on finding new ways to fund more staff and longer visits. “We’ve fundamentally changed the traditional primary care model,” says Rushika Fernandopulle, co-founder and chief executive officer of Boston-based Iora Health, a primary care provider, which launched in 2010. Iora receives fixed, per-patient monthly fees—a system called “capitation”—from the employers, unions and health insurance organizations that contract with it. Because those fees won’t rise to cover the cost of extra care, Iora has an incentive to promote patient health, and its providers work with patients on a range of measures to reduce expensive emergency room and hospital stays. That means not only getting patients to adhere to care plans and take prescribed medications but also, when possible, to eat well and exercise regularly. “We get paid for helping keep people healthy,” Fernandopulle says.

In some 50 practices across the country, physicians at Iora are on integrated teams that include nurse practitioners and behavioral health specialists, among others. A health coach is also assigned to help patients understand and follow through on recommended care. Each doctor is responsible for fewer than 1,000 patients—less than half the size of patient panels in other kinds of practices. Physicians have more time to see patients in the office and to communicate with them between visits. Patients interact with their care teams through phone calls, emails and texts an average of 16 times per year, and come into the office six times. Iora will also arrange transportation to the office for those who might not otherwise be able to get there.

According to the company, hospitalizations and emergency room visits have fallen by more than a third, and patient scores for controlling hypertension, diabetes and other chronic conditions are above national averages. Patients give Iora high marks for satisfaction and engagement, and employee attrition has declined.

CareMore Health uses a similar, capitated model to deliver a more well-rounded experience, including clinics with gyms where patients can work out and, in one notable innovation, a reinvention of the house call. In Connecticut, CareMore serves 2,100 high-needs patients almost exclusively through home visits by physicians, nurse practitioners and medical assistants, with social workers, behavioral health specialists and others brought in as needed. “Seeing patients where they live adds familiarity to the physician-patient relationship,” says Sachin Jain, the physician president and CEO of CareMore. “We get a window on their social determinants of health, the economic and social conditions that can significantly affect their health.”

Jain says their model has led to sharp reductions in hospital admissions and emergency room visits for their patients, who include Medicare Advantage and Medicaid beneficiaries. Another metric of success is the number of requests for information Jain gets from other groups that want to partner to set up a CareMore program. “We’re not even close to where we could be in terms of impact,” he says.

ALL OF THESE MODELS aim to improve the lot of primary care physicians, reducing their burdens and strengthening connections to patients. One model that predates the latest experiments is concierge medicine—in which patients pay retainer fees to physicians on top of normal payments from insurers in return for increased access and additional services. Physicians, in turn, can often afford to spend more time on each case. Another increasingly popular experiment along those lines is “direct primary care,” or DPC, which largely leaves health insurance out of the equation. Patients are charged a flat monthly or annual fee, typically much lower than the price of concierge medicine, for a limited set of primary care services. Those may include real-time access, extended visit times and, in some cases, home visits.

This was the route Julie Gunther chose after leaving her large Idaho group. At her direct primary care practice in Boise she charges adult patients $79 a month for around-the-clock access by phone or email. Core services include physicals as well as diabetes and weight management. Other services are offered à la carte, and patients get large discounts on medications, lab work and imaging. “I love practicing medicine this way,” Gunther says. “It puts the physician-patient relationship back at the center.”

During the past decade, more than 1,200 physician practices have moved to this model, according to the Direct Primary Care Coalition. One big perk is being able to treat many fewer patients than in other settings. A survey by the American Academy of Family Physicians, which supports the concept, found that the average panel size for DPC practices is 600—roughly a fourth of the average for other primary care doctors.

Proponents of the model contend that it delivers better care at lower prices. Such claims have yet to be confirmed, however, says Paul George, associate professor of medicine at Warren Alpert Medical School of Brown University. “We don’t have peer-reviewed data to support anecdotal claims by individual practices,” he says.

Other policy experts worry that the DPC model—and other models that call for the limited number of primary care physicians to see fewer patients—will exacerbate physician shortages. “Every time a primary care physician moves to DPC, what other provider is going to take care of the large number of patients that doctor no longer sees?” asks Carolyn Engelhard, associate professor at the University of Virginia School of Medicine and the Frank Batten School of Leadership and Public Policy. “Are the patients who are left out just going to have to walk into the emergency room?”

Engelhard and other critics also worry that a shift to DPC and other models that require additional fees would disproportionately harm people who can’t afford to pay. The DPC Coalition insists, for its part, that DPC practices serve diverse patient panels that include low-income patients and those who are chronically ill. Some practices have sliding fee scales for patients who may make too much to qualify for Medicaid but who still can’t afford other insurance coverage.

Few of these innovations can promise to broaden access to primary care—a particular concern considering that the Association of American Medical Colleges predicts a nationwide shortfall of as many as 55,000 primary care doctors by 2032. An increasing number of patients, particularly those who are young and healthy, are skipping traditional primary care, opting instead to visit drop-in urgent care centers and retail clinics, and only when they need immediate medical attention. Their relationship to medical care is closer to that of a customer and doesn’t include the traditional physician-patient bond, a dynamic that has been shown in some cases to improve outcomes, George says.

The solution that addresses every part of this conundrum—exhausted physicians, patients who have trouble getting access to a personal doctor and payment models that don’t cover the bases—still seems far away. But as the spirit of experimentation takes hold, and practices refine dozens of approaches, some material improvements are coming to light and, eventually, catching on. “Different health systems in different parts of the country are seeking solutions to different problems,” says Metlay at MGH. “I think it’s likely we’ll end up with an array of primary care models—because no one size is going to fit all.”

Dossier

“Transforming Health Care from the Ground Up: Top-Down Solutions Alone Can’t Fix the System,” by Vijay Govindarajan and Ravi Ramamurti, Harvard Business Review, July–August 2018. Two business professors analyze bottom-up innovations as solutions for transforming health care delivery.

“Powering-Up Primary Care Teams: Advanced Team Care With In-Room Support,” by Christine Sinsky and Thomas Bodenheimer, Annals of Family Medicine, July–August 2019. The authors discuss obstacles that face a new model of primary care provided by a physician-led team.

“Direct Primary Care: One Step Forward, Two Steps Back,” by Eli Adashi et al., Journal of the American Medical Association, August 2018. Experts weigh in on the promise and flaws of DPC models currently underway.

Stay on the frontiers of medicine

Related Stories

- Singular Exceptions

Should primary care physicians be trained to spot unusual, medically important cases?

- For Some Clots, It Takes a Village

Treatment of pulmonary embolisms may benefit from a team approach. But that model faces obstacles inside and outside the hospital.

- Is the "Robot Surgeon" Worth It Yet?

Despite a massive investment by hospitals, the jury is still out on how these machines affect outcomes.