Published On September 22, 2007

SUING A CINCINNATI HOSPITAL FOR THE DEATH of their 39-year-old son, Jim, brought cold comfort to Ray and Arlene Wojcieszak. “My parents cried every day for months, as they were forced to relive Jim’s death over and over during the deposition and discovery process,” says Doug Wojcieszak, Jim’s brother. But their anger over the shocking mistakes made by Jim’s doctors was just as powerful as their grief. They couldn’t forget how the cardiovascular surgeon, “mad as a wet hen,” in Ray’s words, after Jim died during emergency open-heart surgery, told the family he would have performed bypass surgery on the son’s three blocked arteries had Jim’s doctors recognized that a series of heart attacks rather than a bacterial infection was ravaging their patient’s heart. The reason Jim’s condition was misdiagnosed, the family believes, is that the hospital mixed up Jim’s medical chart with that of Ray, his father, whose cardiac stress test, a few months earlier, had revealed a heart as healthy as a 35-year-old’s.

When the family demanded answers from the hospital on why Jim’s heart attacks had been overlooked, “the wall of silence descended,” says Doug Wojcieszak. “Even the surgeon who had been honest the day my brother died told my parents he was no longer allowed to speak to them about the event.”

Jim Wojcieszak died in 1998. The suit was settled in 2000 before trial for an undisclosed amount. Five years later, Doug Wojcieszak started an advocacy group, Sorry Works!, to convince hospitals to abandon their “deny and defend” approach to negligence. What injured patients want, says Wojcieszak, is full disclosure of a mistake, followed by a sincere apology, a promise to fix systems that may have contributed to the error and a timely offer of compensation. “Had the hospital done those four things, what would we have sued over? Nothing,” says Wojcieszak. “If you treat us with respect, we don’t want to own your hospital, your speedboat or your kids’ college fund. We just want what’s fair so we can move on with our lives.”

Yet few people in medicine would feel safe admitting that they were at fault for a poor outcome, and physicians and hospitals have their own list of grievances about the current system of adjudicating claims of medical malpractice. The prevailing view in medicine is that juries lack the technical knowledge required to decide whether the standard of care has been violated. Moreover, although 71% of claims are dropped or dismissed, physicians often must endure the agony of defending themselves against meritless claims while paying a median amount of $15,000 a year for malpractice insurance coverage.

In short, the current system isn’t working well for anyone. Doctors, often reluctant to accept high-risk cases, practice defensively, all too aware that even the appearance of a slipup could land them in court. Though there is no official tally, droves of physicians have left practice, particularly in states with high insurance premiums.

Patients who have been harmed, meanwhile, wait an average of five years to be compensated and typically hand over half of their damage awards to attorneys. And according to a 2006 study by the Harvard School of Public Health and Brigham and Women’s Hospital, justice is not often served. “Overall,” lead author David Studdert concludes, “the malpractice system appears to be getting it right about three-quarters of the time.”

Many legislative solutions have been proposed to reduce burgeoning malpractice costs and make the tort system less adversarial. Yet only a few reforms have made it into law, and though malpractice premiums have leveled off, almost no one thinks the crisis has passed. In 1999 a report by the Institute of Medicine declared that preventable medical errors kill as many as 98,000 people each year in the United States. Even if one accepts the prevailing estimate that only one of five serious injuries due to negligence results in litigation, reducing mistakes appears to be among the best ways to reduce the number of lawsuits. That idea is a core principle of the fledgling patient-safety movement, which argues that not only do patients have the right to know when care has gone awry but also that hospitals have a responsibility to make sure errors are openly discussed so future incidents can be prevented.

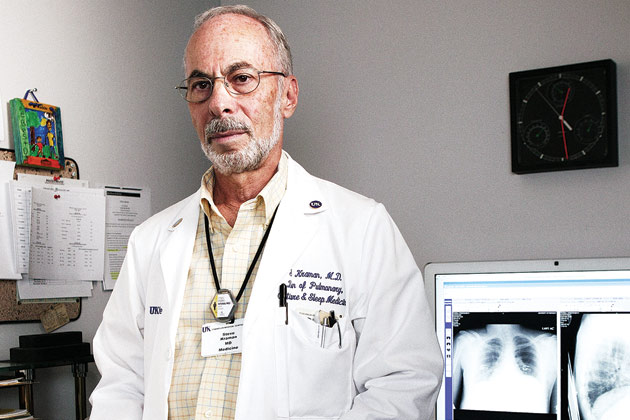

THAT EFFORT TO UNDERSTAND AND MINIMIZE mistakes could, in turn, affect malpractice claims occurred to Steve Kraman, former chief of staff at the Lexington Veterans Affairs Medical Center in Kentucky, after two negligence lawsuits cost the hospital more than $1.5 million. Kraman began investigating adverse outcomes while patients were still in the hospital: “It was just self-interest,” he says. “The hospital attorney and I wanted to do our own discovery before a lawsuit was filed so we could better defend ourselves.”

Then an ethical dilemma arose. Members of the estranged family of a patient who had died as a result of what Kraman terms a “black and white” drug error asked no questions when they claimed her body. Should Kraman tell them the hospital’s mistake had killed her? He did, and promptly wrote a check to the family for $225,000, far less than he would have expected the VA to pay for a wrongful death. Thus began, in 1987, the Lexington VA’s mandatory protocol of immediately determining the cause of every adverse event, disclosing when the standard of medical care had been breached, and negotiating with patients and their attorneys a settlement for economic losses and pain and suffering.

Although the policy would seem to encourage claims, total payouts turned out to be much less than other VA hospitals spent. From 1990 through 1996, the Lexington VA had 88 malpractice claims and paid an average of $15,622 per claim that resulted either in a court judgment or an out-of-court settlement. In the VA system as a whole during that period, the average malpractice court judgment was $720,000, and claims settled out of court paid an average of $205,000.

“We settled almost every case at the hospital, and patients were usually willing to negotiate on the basis of real financial losses rather than out of a desire for revenge,” says Kraman, now professor of medicine at the University of Kentucky. Despite the huge difference in costs, Kraman says it’s impossible to say how much was attributable to Lexington’s policy of admitting mistakes and how much was mere luck.

Kraman and the risk-management staff also bucked tradition by having the hospital’s patient-safety and risk-management committees, ordinarily separate entities, operate as one to help identify problems that contributed to medical errors. “Kentucky has an open-records act that provides public access, so hospitals are very careful what they put on paper,” says Kraman. “They don’t want reporters singling them out as a place in which errors occur. But we were less worried about who knew about our errors than we were about moving quickly to fix them. My feeling was that our responsiveness to adverse outcomes reflected well on us.”

Kraman himself told patients that they had received substandard care, because he felt having the news delivered by the chief of staff conveyed how seriously the hospital took these matters, and it enabled him to know exactly what was said. Although they didn’t admit their errors directly to patients, many physicians involved seemed to welcome this openness.

“Medical malpractice tends to treat doctors and hospitals as if they were criminals by requiring them to remain silent until proven guilty,” says Kraman. “But these are people with high-pressure jobs who sometimes make honest mistakes. Some develop symptoms of post-traumatic stress afterward, and the worst thing is to tell them to shut up, hunker down and maybe it will all go away. It doesn’t go away until you try to make it right and prevent it from happening to someone else.”

Since 2004, all VA hospitals have been required to follow the protocol Kraman established in Lexington.

RICHARD BOOTHMAN HAD A LEG UP ON MOST hospital risk managers when he came to the University of Michigan Health System in 2001. For more than 20 years he had represented doctors as a trial attorney, and he knew enough about malpractice juries not to be afraid to admit that a mistake had been made. “If we apologize to a patient for a medical error, we should mean it, and we should be ready to repeat that apology to a jury if the patient decides to sue,” says Boothman, chief risk officer for the hospital system.

In one case, a jury was told that a mistake by a University of Michigan phlebotomist had resulted in a patient receiving seven units of the wrong blood type, which gave him flulike symptoms for three days. “We told the jurors about the changes we had made to prevent a repeat of that mistake and asked that they evaluate the damages,” says Boothman. The patient had asked for $250,000 in compensation; the jury, perhaps swayed by the hospital’s openness as well as by the relatively minor harm to the patient, returned a verdict of zero.

Claims against the hospital have been steadily decreasing, and though Boothman can’t be sure why, he says the university system’s policy of open disclosure may intercept patients before they feel the need to file a suit. In August 2001, 262 medical malpractice claims were pending against the University of Michigan, compared with just 83 in August 2007.

In another incident, a University of Michigan pathologist interpreted a biopsy of a patient in her seventies as a recurrence of lung cancer, and the patient’s physician broke the news that she might have as little as six months to live. Two years later, the patient was still alive, and the hospital discovered the pathologist had erroneously read an inflammation of her lymph nodes as cancer cells. “We could have let her believe she was a medical miracle, but we decided to tell her the truth,” says Boothman. He stresses, however, that the decision to disclose was made only after other pathologists confirmed the error.

“If half of the pathologists we consulted had read the biopsy as a recurrence of cancer, I’m not sure we would have apologized,” Boothman says. Although the patient initially claimed her emotional distress was worth $250,000, she ultimately accepted the university’s offer of less than $100,000. And because the hospital instituted a system of randomly double-checking pathology results, she returned as a patient.

“The real key,” says Boothman, “is to relegate litigation to the role it was meant to play, as a last resort for resolving disputes that the parties can’t resolve. About a quarter of the claims we attempt to settle do get litigated. I could drop our defense costs to zero by settling every claim, but that isn’t a gauge of success.”

THAT THE VA AND AN ACADEMIC MEDICAL CENTER should take the lead in heading off malpractice claims should come as no surprise. Such institutions employ and insure their medical staffs, which makes it easier for hospital and physician to take a united stand on disclosure and compensation. Community hospitals, on the other hand, often engage in a tug-of-war with doctors in private practice over whose insurer will cover a lawsuit. Moreover, self-insured physicians usually aren’t eager to take responsibility for errors, fearing their rates will skyrocket or their policies will be canceled.

In a closely watched experiment that began in 2000, COPIC Insurance Company, which insures 7,000 private-practice doctors in Colorado and Nebraska, gives physicians the chance to stay in the good graces of patients with an offer of as much as $30,000 to compensate for hardships caused by an adverse outcome. Physicians are encouraged to communicate openly, and if appropriate, apologize. And because patients don’t make a formal written demand for compensation or waive their right to sue later (after they accept the check), doctors avoid having their errors reported to the National Practitioner Data Bank and the state licensing board. Patients who want to receive cash awards are prohibited from being represented by an attorney. “As soon as lawyers get involved, the process becomes adversarial,” says Alan Lembitz, vice president of risk management for COPIC. “We’re trying to foster good communication between patient and doctor.”

The process isn’t a cure-all. Seriously injured patients aren’t likely to be assuaged by an apology and a small payment, and the system works better for surgeons than for internists or family physicians. “Doctors who perform procedures usually know right away that things haven’t gone well, whereas a missed diagnosis may not come to light for months or years,” says Richert Quinn, a physician risk manager at COPIC.

While the insurer’s program has resulted in more patients receiving payments than under the old system, each payout has been relatively small. During the past six years, a quarter of the 3,200 patients with adverse events fitting the program’s criteria received an average $5,400. (The program has a specific set of exclusions, such as a doctor’s obvious negligence or a patient’s death.) Only seven compensated patients went on to sue, and two received payment through the tort system.

What happened to the 75% of patients who may have been harmed and fit the criteria but got no payment? In some cases, say Lembitz, physicians decided their patients had recovered sufficiently and required no economic assistance, while in others, patients turned down the offers, and still others had more serious outcomes than the program was designed to address. Of those who didn’t receive compensation, 16 sued and six received payment via the tort system. “The program hasn’t had a negative effect on our operational costs,” says Quinn, and while it may not be saving money, he thinks it helps preserve relationships between patients and their doctors.

IN 1999, WHEN LINDA KENNEY WAS ABOUT TO undergo ankle-replacement surgery at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, anesthesiologist Rick A. van Pelt inserted a needle behind her knee to administer a nerve block and, seeing no blood, assumed the needle was in the right place. But in less than a minute, Kenney had a seizure, then went into full cardiac arrest. A heart team took over, and her chest was cracked open. The surgery succeeded, and although Kenney was in bad shape—chest wired shut, ribs broken, short-term memory loss—she was told she was lucky to be alive.

Shortly after she was discharged, though, Kenney received a letter of apology from van Pelt. And in a phone conversation with her six months later, he explained that her cardiac arrest had apparently resulted from the drug he administered, possibly because the needle had hit a broken blood vessel. Van Pelt told her that the hospital had prevented him from talking to her while she was an inpatient because of the litigation risk, and he “was expected to function as if nothing had happened,” coping with “the guilt, vulnerability and shame on my own.”

Kenney declined to sue, and doctor and patient decided to take their story public, repeating it during appearances in the United States and abroad to promote the idea that both patients and providers have emotional needs after a mishap. At Brigham and Women’s, staff members can request peer-to-peer support sessions—modeled after those used by Boston’s firefighters, police and emergency medical services teams—to help them deal with their own reactions. “If you support your providers this way, it’s logical for them to want to talk to the patient and family about what happened,” says van Pelt.

Yet such openness remains rare, in part because of litigation risks when mistakes are acknowledged. Although many states have laws preventing physicians’ apologies from being used against them in court, plaintiffs’ attorneys often view such admissions as a smoking gun. And despite success at a few institutions that have owned up to medical mistakes, checkbook in hand, most hospitals and doctors resist the notion.

In a recent survey of surgeons and primary care physicians, Thomas H. Gallagher, associate professor of medicine at the University of Washington in Seattle, found that while 80% said they would tell a patient about an obvious error—a sponge left behind during surgery, say—only half would disclose a mistake that the patient wouldn’t detect, such as an episode of tachycardia caused by overlooking lab test results showing elevated potassium levels. Just one-third would apologize for any error.

“Patients really care about having an error explicitly acknowledged, but physicians struggle with how much information to provide,” says Gallagher, who believes there’s a need for standards that clearly outline what doctors must tell patients and what situations might justify disclosing less. “Physicians should feel comfortable that disclosure is the right thing to do and that it is likely to have a positive effect on malpractice litigation,” he adds. Within a decade, “full and frank disclosure to patients is likely to be the norm rather the exception,” he predicts—and a major step in “restoring the public’s trust in the honesty and integrity of the health care system.”

Dossier

“Medical Liability: Beyond Caps,” Health Affairs, July/August 2004.Excellent overview of the current medical malpractice crisis, including articles that explore ideas for an improved litigation process and offer a look at California’s long-standing tort reform.

“Disclosing Medical Errors to Patients: Attitudes and Practices of Physicians and Trainees,” by Lauris C. Kaldjian et al., Journal of General Internal Medicine, July 2007. A look at how often physicians say they admit to medical errors—and how infrequently they really do.

“The Sorry Works! Coalition: Making the Case for Full Disclosure,” by Doug Wojcieszak et al., Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Patient Safety, June 2006. Wojcieszak lays out the challenges hospitals face in compensating patients for mistakes—and cogently dismantles each argument for why such a protocol won’t work.

Stay on the frontiers of medicine

Related Stories

- The Upside to Full Disclosure

After instituting “disclosure, apology and offer” policies, hospitals have seen a drop in malpractice lawsuits.