Published On July 21, 2010

WHEN JOHN PARRISH RETURNED from his year in Vietnam, he resumed a life that would be filled with professional accomplishments. A pioneer in his field, Parrish would go on to serve for two decades as head of dermatology at Massachusetts General Hospital and to become a leader in translating technological advances into new medical treatments. He has written six books and hundreds of journal articles, and has won national and international awards.

Yet like so many fellow Vietnam veterans—and like those scarred by experiences in other wars, past and present, or at home—Parrish was living a double life. Even as he moved further and further from his days as a battlefield physician for the Marines, the images and fears kept surging back. During his year in the war, 1967, Parrish had treated a stream of horribly injured soldiers and civilians, routinely making split-second decisions about which of the wounded to try to save and which to let die. He had also faced personal dangers ranging from frequent mortar fire to nearly losing his life in a helicopter that crashed behind enemy lines. Through it all, he had barely flinched. “I was able to stay totally intact emotionally, because I had so much work to do and couldn’t react to all that was happening around me,” Parrish says. “But when I got home, I had difficulty letting go of some of the things I had witnessed.”

In 1972, as a sort of therapy, Parrish published 12, 20 & 5: A Doctor’s Year in Vietnam—the numbers are medic shorthand for how many incoming casualties were stretcher-borne, walking or dead—based on his experiences. Even after the book was released, he continued to rewrite the manuscript. “I couldn’t stop working on it, trying to get it right,” he says. And often, when Parrish’s wife and children were away from the house, he would play recordings of battle sounds, machine guns, bombs, screaming voices. When the pressure of his memories became too great, Parrish sometimes spent nights walking the streets, stopping at veterans’ shelters or sleeping in his office. “I was a street person at night and professor and chairman of a department by day.”

Though Parrish hardly fits the stereotype of a psychologically damaged veteran unable to function in civilian life, his flashbacks, nightmares and other symptoms are shared by all too many who’ve come home to worlds so different from the front lines. And while the roots of that psychic burden extend back thousands of years, what we now call post-traumatic stress disorder, or PTSD, has only recently been recognized as a single condition that may afflict anyone who has lived through a searing event. Sufferers include battered spouses, abused children, victims of car accidents and those who have witnessed violent crimes or natural disasters. With American wars being waged in Iraq and Afghanistan, much of the latest research has focused on how to treat hundreds of thousands of young men and women returning from the battlefront with mental as well as physical pain.

Part of that effort involves ongoing attempts to understand what really occurs in the brains of PTSD sufferers, and a few drugs are showing promise in keeping damaging memories at bay. Other groundbreaking work in cognitive behavioral therapy, or CBT, a systematic, goal-oriented technique that seeks to alleviate symptoms, also has moved forward. The military establishment, including the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, now seems determined to anticipate and treat psychological wounds, after a long history of underplaying or even ignoring the problem. The Department of Defense and Congress have earmarked millions of dollars for studying and implementing new treatments for the disorder.

Yet even the most effective therapies will have no impact unless PTSD sufferers seek help, and finding ways to overcome its stigma has emerged as a crucial component of efforts to combat this disorder at a time when so many are being exposed to its causes. A 2004 study found that more than 90% of Marines who had served in Iraq had experienced attacks or ambushes, 75% had seen dead or seriously injured Americans, and more than half had handled or uncovered human remains. Those are exactly the kinds of events that may lead to PTSD, and a major 2008 study by the RAND Corporation’s Center for Military Health Policy Research estimated that almost 300,000 veterans of today’s wars may suffer from psychological disorders. Such findings suggest a looming public health crisis.

Tim A. Hetherington/Panos

PTSD HAS GONE BY DIFFERENT NAMES in its long history. During the Civil War, more than 5,000 Union soldiers were diagnosed as suffering from nostalgia—a term coined during the seventeenth century by the Swiss physician Johannes Hofer to describe psychological disorders experienced by civilians far from home and mercenaries fighting in distant lands. “The idea was that someone from Massachusetts, marching with Sherman toward Atlanta, was so homesick for New England that he was psychologically incapacitated,” says Matthew J. Friedman, a psychiatrist at Dartmouth Medical Center and executive director of the National Center for PTSD, operated by the Department of Veterans Affairs. During the First World War, explosives unleashed upon soldiers in the trenches created shell shock; a generation later, soldiers were said to suffer from battle fatigue. In Southeast Asia, it was post-Vietnam syndrome. Among civilians, abused spouses who couldn’t shake memories of their beatings were said to suffer from battered wife syndrome, rape victims from rape trauma syndrome and mistreated children from abused child syndrome.

Now all of that comes under the umbrella of PTSD, recognized officially in 1980, when the American Psychiatric Association included the condition in its Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. This was a crucial step forward in finding unified answers to a problem that has often seemed to stem from disparate causes. “Physicians began to understand that the clinical expression of a number of disorders was pretty much the same,” Friedman says. “There seemed to be a distinct pattern of symptoms that characterized people who had survived but hadn’t been completely successful in coping with traumatic stress.”

In many people with PTSD, there’s a tendency to repeat an experience over and over through flashbacks or nightmares. Certain noises or smells may transport a sufferer back to the moment when the trauma occurred. Emotional numbness is another common symptom; so is hyperarousal, with awareness of the tiniest details—a truck backfiring in the distance, the faces of passersby on a busy sidewalk—as if always on the alert for danger. In many cases, there are accompanying problems with alcohol or drug dependence, domestic violence and homelessness. Often symptoms appear months or even years after the initial trauma.

Though battle deaths for the current wars have been sharply lower than during past conflicts, the conditions of warfare, in which troops must be on constant alert for roadside bombs and suicide bombers, put soldiers at high risk for stress-related trauma. Moreover, many of the estimated 1.6 million troops who have been deployed to Iraq or Afghanistan are called back for multiple tours of duty. And with better gear and medical treatment, they’re more likely to survive grievous injuries, with about one in nine wounded dying in Iraq, compared with a third of casualties who succumbed in Vietnam and about two of five in the Second World War. “Because of fantastic logistical support, medevac capabilities and medical advances, people who would have died in past wars are surviving their wounds,” Friedman says. “But they are at very high risk for psychological difficulties.”

THE QUESTION OF WHY TRAUMATIC EXPERIENCES return so disruptively has sent researchers deep into the brain to where memories are formed, re-formed and stored. Think of a computer with large but finite storage. The goal is to save key data without wasting space on trivial or repetitive information. Most daily events—the ham sandwich you ate for lunch, a walk up stairs—are soon forgotten. But choke on the sandwich or trip on the stairs, and a lasting memory results. Such memories are consolidated for long-term recall—stored, so to speak, in the brain’s computer. Though they don’t occupy every conscious moment, they return when needed, with vivid detail, helping to guide better behaviors, like chewing more carefully or holding tight to that railing.

Scientists think some experiences, such as witnessing the death of a close friend in combat, living through an explosion or being raped, are so powerful that they may overload the brain’s ability to synthesize and safely store those memories for use only when needed. Instead, images and feelings force themselves back from storage often and unpredictably, sometimes in debilitating ways.

Researchers aren’t seeking to erase the bad memories entirely, because those experiences, while traumatic, are important parts of a person’s life experience. Rather, they’re seeking ways to make those memories more manageable. “A lot of evidence suggests that stress hormones potentiate the storage of long-term memories, a process called consolidation,” says Roger Pitman, a psychiatrist at the MGH who has spent nearly 40 years studying the effects of combat on soldiers and Marines, and who helped launch Home Base, a program started in September 2009 jointly by the MGH and the Red Sox Foundation, designed to reduce the stigma of PTSD and encourage more veterans to get treatment (Parrish is the program’s director). “Our theory is that at the time of traumatic events, an excess of stress hormones produces a very strong consolidation of traumatic memory, which can last a lifetime.”

In seeking to reduce the terrifying impact of these memories, researchers have focused on the amygdala, a small, almond-shaped structure in the brain’s deeper temporal region thought to process emotional reactions. Studies by Pitman and others have shown that propranolol, a beta-blocker used to regulate heartbeats in arrhythmia patients, may work in the amygdala to help counteract the effects of stress hormones released when memories are recalled. “Preclinical research suggests that propranolol selectively blocks the emotional response of the memory rather than the factual recall,” Pitman says. “You’d remember what happened but without the emotional arousal. That’s the most desirable outcome in treating PTSD.”

A recent study by Pitman and others in Montreal, involving 50 subjects, found that propranolol reduced PTSD symptoms by about half, roughly the same effect as cognitive behavioral therapy. But Pitman describes the results as preliminary, because the study subjects knew they were getting propranolol and not a placebo. (The team recently started a double-blind trial that includes placebos.)

Seeking more powerful drugs, Pitman and other scientists considered anisomycin, an antibiotic that inhibits protein formations and that proved effective but toxic. Pitman recently began experimenting with mifepris-tone, or RU-486, better known as a “morning after” contraceptive. In addition to blocking production of progesterone (a hormone essential to maintaining pregnancy), mifepristone blocks the formation of cortisol, a major stress hormone. In a study involving rats, Pitman found mifepristone to be three times as powerful as propranolol in reducing fearful memories, and he and his colleagues have begun a human study involving mifepristone.

WHILE SUCH EXPERIMENTS may eventually yield important new treatments, most current approaches involve one of the methods known collectively as cognitive behavioral therapy, which may encourage patients to understand and face their fears, gradually helping them distinguish between real and imagined dangers. “In some situations—say, if a tiger comes into your office—it’s correct to be afraid and to try to protect yourself,” says Edna B. Foa, professor of clinical psychology in psychiatry at the University of Pennsylvania and director of the Center for the Treatment and Study of Anxiety. “But people with PTSD tend to believe that everything and every place is dangerous.”

Scarred by memories of roadside bombs in Iraq, veterans may avoid highways back home, or swerve or speed up if they spot an object along the road. With CBT a therapist might have a patient repeatedly go out on the highway to emphasize that there’s no real danger, and supplement that experience with discussions that may ease anxiety. “We go back to the event and recount it in the present tense for 45 to 50 minutes a session,” says Barbara Rothbaum, director of the Trauma and Anxiety Recovery Program at Emory University in Atlanta. “Patients get a tape they can listen to every day. After they’ve processed their memories, we talk about the experience.” Often they feel guilty about things that were beyond their control, such as surviving an explosion in which several fellow soldiers died, she adds. Now Rothbaum and others are experimenting with an enhanced kind of exposure therapy called Virtual Iraq, developed by University of Southern California clinical psychologist Albert Rizzo. Researchers use stereo headphones and a head-mounted display with a separate screen for each eye to enhance three-dimensional realism. The user sits in an enclosed chamber on a raised platform that can vibrate and rumble like a Humvee rolling across the desert. Researchers gradually add to the realistic visual scenes the sounds of gunfire, incoming mortar rounds, helicopters, wind and screams. A separate machine even pumps in smells of burning rubber, sweat, diesel fuel and exotic spices. “Smell is our strongest memory,” Rothbaum says. “Our olfactory bulb goes straight to the amygdala.”

Though results are preliminary, Rothbaum has reported the case of a 29-year-old, college-educated Army National Guard combat engineer who was experiencing nightmares, night sweats, difficulty functioning at home and at work, irritability and hypervigilance. Virtual Iraq prompted him to confront painful memories—for example, being covered with blood and dirt after an explosion. His perspective on the events changed markedly from feelings of grief and horror to pride in himself and in other soldiers. According to the standard diagnostic tool for PTSD—a 30-item questionnaire that checks for 17 symptoms of the condition and asks about how well a person is functioning in social or work situations—the soldier originally had a score of 106, well above the threshold for severe impairment. After he went through CBT using Virtual Iraq, his score dropped to 47, indicating only moderate symptoms.

EVEN AS RESEARCH ADVANCES, one fundamental problem remains. Soldiers, trained to be tough and self-reliant, are often loath to admit they have a problem and to look for help. Experts estimate that no more than half of the veterans who would meet the clinical threshold for PTSD ever seek treatment.

“The major thing that impedes our progress is the stigma associated with PTSD,” says Parrish, who eventually found help through CBT and medication, though he continues to struggle with memories of his time in Vietnam. “It’s very countercultural to admit you have a weakness or these symptoms.”

There’s also the perception—and often the reality—that admitting to a psychological problem can stunt a career both within the military and in civilian life. “Warriors who are on active duty won’t let anyone know they’re having symptoms, because their commanding officer won’t trust them anymore or won’t send them on missions,” Parrish says. “They won’t get promoted. And once they leave the military, they worry they can’t get a job on the police force or in the fire department because their record shows they have psychiatric problems.”

One way to encourage more people to get treatment is to demystify PTSD, and the U.S. military has been developing programs to raise awareness of the disorder. These include efforts to give information about the psychological dangers of battle to soldiers before they are deployed. Though a modest first step, Battlemind Resilience Training, launched by the Army in 2007, now provides one hour of training prior to deployment, one hour upon return from a combat area such as Iraq or Afghanistan, and one hour three to six months after the soldier has returned. A study of 629 soldiers returning from Iraq, conducted shortly after the program started, found 14% fewer PTSD symptoms among soldiers who had undergone Battlemind than among those in the control group. Soldiers reported a greater sense of community and awareness, with 78% saying they could better identify fellow soldiers at risk for PTSD and 83% feeling confident they could take positive steps to lessen mental problems that might arise. By contrast, 63% of those who had not undergone the training were that confident.

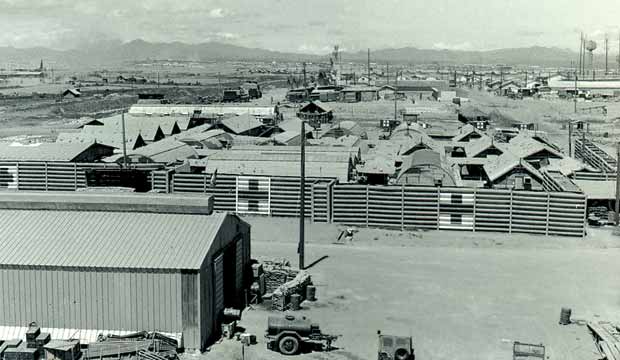

Post-traumatic stress disorder may bring even the distant past terrifyingly to life. Here, John Parrish returns from a patrol near Dong Ha, Vietnam.

The training also encourages veterans, who often withdraw emotionally from loved ones, to share their experiences. “We highlight what happens if you don’t tell your spouse what’s going on,” says Carl Castro, director of the Military Operational Medicine Research Program at Fort Detrick, Md., and a co-creator of Battlemind. “It doesn’t have to be the gory details. But give them some idea of what you’ve been through. Otherwise, how are they going to understand you?”

Even if soldiers don’t actively seek treatment, if their physicians recognized PTSD symptoms, they might encourage their patients to consider therapy. But while awareness of the condition has increased, “evaluation of military service–related difficulties is not part of the training and practice for most civilian doctors,” says Mark Pollack, director of the Center for Anxiety and Traumatic Stress Disorders at the MGH and chief medical officer of Home Base. “It isn’t their typical practice, when someone walks in who isn’t in uniform, to ask about military service or recent deployments.”

Doctors involved with Home Base are, of course, acutely aware of PTSD, and veterans of Iraq and Afghanistan can receive treatment and therapy (as can their families) at the Home Base Clinic, which offers a multidisciplinary staff of psychiatrists, psychologists, nurses, social workers and other MGH clinicians. At the same time, Home Base personnel know that they and other specialists at PTSD centers around the country, including Veterans Affairs hospitals and other military facilities, see only a fraction of veterans dealing with the problem. That’s why a primary goal of Home Base is to educate clinicians about the possibility that the young people they are treating for sleep disturbances or a variety of physical symptoms, even pain, may be veterans dealing with PTSD.

And service members often aren’t forthcoming. The involvement of the Red Sox Foundation in Home Base may help destigmatize PTSD, with pro athletes openly supporting veterans in their struggle. But changing attitudes isn’t easy. “When they leave the combat environment, veterans are anxious to get home,” Pollack says. “The idea of having to enter treatment, for many, is disheartening. People like to put their experiences behind them and move on. It can really cast a shadow over not just their lives but those of the people they’re involved with.”

The family component is crucial. Paula Rauch, an MGH child psychiatrist and specialist in pediatric trauma, is working with Home Base to widen the scope of PTSD diagnosis and treatment to include family members, who often experience significant stress in dealing with returning veterans. According to a study in the journal Pediatrics, as of 2006 almost 2 million American children had at least one parent in active military duty or in the reserves. Published in December 2009, the study found that children of military personnel deployed to Iraq and Afghanistan suffered a significantly higher level of emotional difficulties, when compared with studies of other children.

Though the study didn’t specifically consider PTSD, the disorder cannot help but complicate a returning veteran’s already challenging family situation, Rauch says. “Think about what children need to feel secure,” she explains. “They want a parent who’s warm, predictable and easily engaged. They need consistent rules, parental approval and a calm, loving home environment.” When a father or mother seems distant, children often feel confused, blame themselves or assume that the parent doesn’t love them.

The emerging focus on family members is one more indication that research on PTSD, a disorder that’s finally recognized as real, dangerous and often intractable, is entering a period of enhanced scientific scrutiny. Researchers say it is unlikely that any single treatment will prove to be the ultimate answer or that PTSD can ever be eliminated. But for people such as Parrish, who is now taking a lead in efforts to lessen the impact of a condition that has been part of his life for more than 40 years, recent progress is undeniable—and long overdue.

Dossier

Invisible Wounds of War: Psychological and Cognitive Injuries, Their Consequences, and Services to Assist Recovery, edited by Terri Tanielian and Lisa H. Jaycox (RAND Corporation’s Center for Military Health Policy Research, 2008). This landmark 499-page study found that approximately 20% of service members may return from the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan with such mental health conditions as PTSD and depression.

Treatment of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: An Assessment of the Evidence, by the Institute of Medicine’s Committee on Treatment of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (National Academies Press, 2008). This report, commissioned by the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, calls for greater uniformity and coordination of research to show conclusively the best approaches to treatment.

“Combat Duty in Iraq and Afghanistan, Mental Health Problems, and Barriers to Care,” by Charles W. Hoge et al., The New England Journal of Medicine, July 1, 2004. A widely cited study of PTSD and other mental health disorders afflicting veterans of Iraq and Afghanistan.

Stay on the frontiers of medicine

Related Stories

- PTSD Timeline: Centuries of Trauma

A brief history of the observation and study of PTSD

- Foreign Wars, Domestic Tragedies

Families of returning veterans sometimes develop mental health problems of their own. An MGH team studies the problem and looks for solutions.