Published On May 3, 2006

TWENTY-FIVE YEARS AGO, CASUAL SEX carried little fatal risk, and homosexuality was seldom discussed in mainstream society. But all that changed during the summer of 1981, when several gay men in New York and California died of rare infections their bodies should have fought off with ease. The emergence of a new affliction, soon christened with what became a terrifying acronym—AIDS, for acquired immune deficiency syndrome—led to seismic shifts in sexual attitudes and forever changed the relationship between patients and the medical system.

Few people had a more intimate view of those changes than Anthony S. Fauci, Robert C. Gallo, Mathilde Krim and Bruce Walker. In 1981 the four were at different stages of medical careers that might have been spent quietly toiling in labs and clinics. Yet by fate and by choice, they found themselves at the front of the race to unlock the secrets of a new disease. In the years that followed, they took on unfamiliar, often uncomfortable roles—as targets (and later allies) of activists; as politicians and educators; as diplomats and foreign aid workers.

Here, the four describe what they’ve learned during a quarter-century of fighting AIDS. Their insights extend beyond AIDS to inform our understanding of how medicine should solve essential problems, whether cancer or the next pandemic.

I got goose bumps when I read the first reports of pneumocystis and Kaposi’s sarcoma in the summer of 1981. These two conditions are usually found in people with suppressed immune systems, such as those undergoing chemotherapy. That they were occurring in gay men in both New York and California suggested we were dealing with something infectious, possibly sexually transmitted and definitely new.

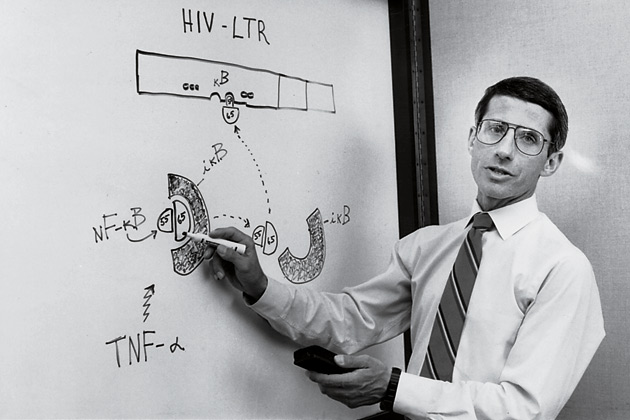

As someone trained in both immunology and infectious diseases, I felt as if I were somehow cut out to study this new syndrome. I put together a team, and we did research all day, then stayed up at night seeing very sick patients, almost all of them dying. I realized that if this disease were sexually transmitted, there was no way it would stay confined to the gay community. But it would take a long time to change the perception that AIDS was a disease of gay people. When I pushed aside my other research to focus exclusively on AIDS, my mentor asked, “Why are you diverting a great career for a disease involving 40 people?”

In 1984 I became head of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases and began pushing the Reagan administration and Congress for more funding for research, which we finally got. The irony is that because I was the one making noise about the disease, I became the public face of government in the eyes of AIDS activists. Larry Kramer, the founder of the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power, attacked me in the media. His group would say, “Fauci, why are you killing us?” I’d think, I’m not killing you—I’m trying to help you!

One day the activists were demonstrating on our campus, and I invited several up to my office. They were shocked—no one had ever seriously listened to them before. There was this attitude that the science would be contaminated if you brought nonscientists into the process. But once you got past the theater, the activists were making a lot of sense—why shouldn’t someone with weeks to live, for example, be allowed to take an experimental drug?

That meeting opened a dialogue between the activist community, doctors and regulators that led to many important changes, including how the Food and Drug Administration runs clinical trials and approves new treatments. Our interactions also proved that the constituency of a disease can have important input into the scientific and regulatory process. This has transformed medicine, and now we see activists for virtually every type of disease. That first meeting also led to a truce with Kramer, who has become one of my closest friends.

AIDS has proven that if you put a lot of money into solving a problem and plan carefully, you can produce almost unimaginable levels of scientific achievement. There are now more FDA-approved antiviral drugs for HIV/AIDS than for all other viral infections. We got this far by galvanizing the government and the scientific community to work on this challenge even before the rest of the world realized its importance.

The area of research I consider most exciting today is also the most sobering—coming up with a vaccine. HIV is unique in that the body cannot produce neutralizing antibodies against the virus. This has prevented us from creating a vaccine in the usual way—introducing something that closely mimics the virus in order to build up immunity. A vaccine against HIV will most likely look very different from what we’ve used against such viruses as smallpox and measles. I don’t know how long it will take, but I plan on staying involved until we get there.

In late 1981 and early 1982, I attended a series of lectures at the National Institutes of Health given by James Curran, the coordinator for the Centers for Disease Control’s task force on AIDS. All kinds of ideas were floating around about what was causing this new disease—including the use of nitrate inhalants by gay men—but Curran thought the cause was infectious and probably viral. At the second lecture, he looked right at me—or so it felt—and asked: “Where are the virologists?” On the walk back to my lab, I began thinking about the disease.

Although I was a cancer specialist, my research had long focused on retroviruses, which cause certain cancers. Our lab had just discovered the first human retrovirus, human T-cell lymphotropic virus (HTLV), and there were clear parallels with what we were seeing in AIDS. Like HTLV, the new disease seemed to target a part of the immune system known as CD4+ T-helper cells, and also like HTLV, risk factors were related to sex, blood and having an infected mother. Moreover, as Max Essex, a colleague at Harvard, reminded me in a telephone call, certain animal retroviruses can cause immune suppression. It began to seem as if AIDS might be caused by a retrovirus, which meant our lab was uniquely positioned to help.

These intellectual proddings led us to begin studying the disease, paving the way for several breakthroughs between 1982 and 1984: our discovery of the HIV virus with Luc Montagnier’s team at the Pasteur Institute in Paris; proving that HIV causes AIDS; and developing the HIV antibody blood test. I knew a test was vital not only for humanitarian reasons but to establish credibility for the link between HIV and AIDS. Not only did the test save countless lives, it also allowed the epidemic to be properly followed, cleared the way for education programs, and opened the door to early therapy because HIV-positive people could now be identified.

After the test hit the market, I became a target of activists. I didn’t understand why until one of them told me, “You’ve created a test branding us as carriers of disease, without giving us any hope for treatment.” They did not understand the advances the blood test would soon allow, nor had I ever thought of their concerns. Soon I began to patch things up with the activist community and made many good friends. During the fierce political battles I fought in the late 1980s, their support was sometimes the only thing that kept me going.

The development of the HIV test by the spring of 1984 was a historic achievement for American science. The Department of Health and Human Services and the NIH deserve credit for protecting much of the world’s blood supply by virtue of the speed with which they licensed the test. The question that haunts me still, though, is: Could we have done even better, even faster? During the eight-to-nine-month window after the test was developed and before it was licensed, a limited number of blood samples could have been tested, possibly saving even more lives. But this in itself would have posed the dilemma of how to select a very few samples from the many that needed testing.

The lesson is that scientists can’t just leave it to others to find applications for their discoveries. We must ask, “How can we make these results more practical sooner rather than later?”

In early 1981, a friend confided: “I’m losing my touch as a physician. I have these patients, all gay men, who have swollen lymph nodes, but I can’t help them.” It was a moment of premonition, followed weeks later by another.

I had been studying interferon as a possible antitumor agent, and was looking for cases of tumors visible on human skin. Our in-house dermatologist told me, “You’re very lucky. There’s a cancer called Kaposi’s sarcoma that produces very visible tumors. Until recently I’d seen only nine cases in 25 years, but I now have 12 on my ward.” Again, all were gay men.

I brought the doctors together, and hearing of similar cases elsewhere, we formed a study group. What began as a medical riddle soon turned tragic. Some of our patients were dying—and, because many of these men knew one another, they became terrified, as did their physicians.

This early involvement led me to found the AIDS Medical Foundation, the precursor to amfAR, in 1983 to stimulate and fund AIDS research. The public health system was very slow to respond to AIDS. Federal research funding didn’t become adequate until 1987, after it had become clear to legislators that many people other than gay men were getting the disease. If not for Gallo and Montagnier, who had worked with animal retroviruses, I hate to think how long it would have taken to discover HIV.

During the mid-1980s, much of society moved from indifference to irrational fear. I had grown up in Europe during the Holocaust, and when certain politicians in this country began suggesting mandatory testing and rounding up those “suspected of being at high risk,” namely gay men, I grew afraid. We avoided such horrors because some people spoke out using scientific evidence and common sense to combat panic and homophobia. No one played a more crucial role than then Surgeon General C. Everett Koop, who sent a pamphlet to 100 million U.S. households explaining AIDS and its possible prevention.

To this day, AIDS remains a special threat not only to public health but also to the social order. The condition carries a unique stigma that has required, for individual protection, the institution of certain procedures previously unknown in public health, such as anonymous testing sites and informed-consent forms to be signed by every person tested.

It amazes me that easy, cheap HIV tests are not routinely used during doctor’s visits. When I asked mine why he didn’t offer to test me, he said, “The kind of women I see don’t get AIDS.” It is largely because of such ingrained, misguided ideas that so many people don’t know they are infected.

While the search for an HIV vaccine gets much attention, there are other frontiers to conquer. Antiretroviral drugs reduce the amount of virus in the blood, but only work against an actively multiplying virus. HIV also has a stealth form that hides in certain immune system cells. Under treatment, the virus may become undetectable, but if treatment is stopped, HIV can return within days to its previous high levels. Important research is taking place on how to trigger the virus out of its dormancy so that antiretroviral treatment can get completely rid of it. That would be tantamount to achieving a cure.

My first encounter with AIDS came in 1981. A patient arrived at the emergency room with three simultaneous life-threatening diseases, something none of us had ever seen. As an intern, this was an eerie, memorable moment, the first time the people I considered the smartest in the world—the physicians training us—were stumped too. Similar cases followed, and we realized we were seeing something entirely new. I wanted a career in which I could use my skills as both a researcher and a physician, so I chose infectious disease as my specialty and focused on AIDS.

Mass General was early to set up a dedicated clinic for AIDS, which made the hospital a very fertile place to study the disease. You could apply what you saw in patients to basic research in the lab. Our patients have taught us a great deal about how the body fights back against AIDS.

In 1994 a man came to the Mass General outpatient clinic. He told me he was a hemophiliac who had been infected with HIV more than a decade earlier. “But I’ve never had any symptoms, never been treated with AIDS medicines, and I feel great,” he said. “Am I still going to die?”

We could document that he had been infected but found no virus in his bloodstream. We began to try to understand how this man and a small number of others, now known as “elite controllers,” were achieving this remarkable outcome. They might hold the secret to how the body’s immune defenses keep HIV in check. That would be almost as good as a vaccine.

Part of the answer seems to be that elite controllers produce a very large number of cells—known as T-helper cells—that allow the body to recognize and attack HIV. We are now conducting clinical trials in which we try to boost this response in patients already infected with the virus. And we will soon begin seeking additional answers in elite controllers’ genetic makeup that allow such incredible success against the virus.

My experiences have convinced me that great advances in biomedicine come when you link research to clinical care. This is a lesson we’re taking to the heart of the AIDS epidemic in sub-Saharan Africa, where almost no basic research has taken place. In 2003 we opened a research and care facility in Durban, South Africa, with the Nelson Mandela School of Medicine, where we are trying to understand the viruses fueling the African epidemic and helping to create improved treatment programs. In another program, residents can work at a hospital in rural South Africa. It is a global epidemic, and it is exciting to be involved where the need is so great. After 25 years, AIDS still takes a terrible toll, but I have to believe that this is a solvable problem.

Dossier

“In Their Own Words: NIH Researchers Recall the Early Years of AIDS.” An online trove of oral histories, original documents and time lines, recounting the efforts of NIH physicians, scientists and officials to confront the AIDS crisis.

Virus Hunting: AIDS, Cancer, and the Human Retrovirus: A Story of Scientific Discovery, by Robert C. Gallo [Basic Books, 1993]. No scientist was more enmeshed in the politics of AIDS research than Gallo, who here answers his critics in an exhaustive—though often slow-going—account.

Shots in the Dark: The Wayward Search for an AIDS Vaccine, by Jon Cohen [W.W. Norton, 2001]. A perceptive critique of the bureaucratic wrangling, marketplace failures and personal rivalries that have held back development of an AIDS vaccine.

Stay on the frontiers of medicine