Published On January 22, 2019

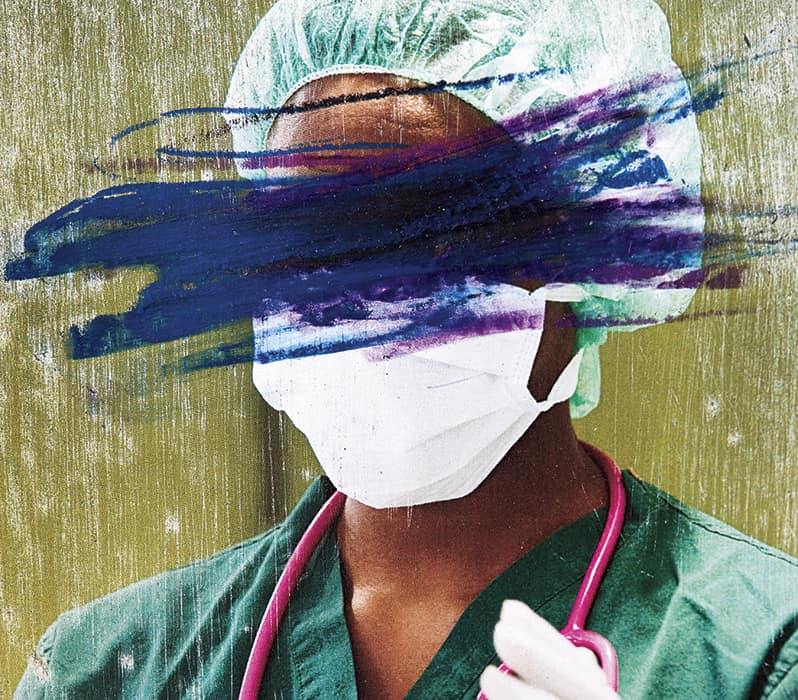

ALLYSHA SHIN CLEARLY REMEMBERS only the first kick and punch to her face. “Everything happened so fast,” says Shin, a neuroscience nurse at Keck Medicine of USC in Los Angeles, who was attacked by a patient on a December night two years ago. Hours into her graveyard shift in the intensive care unit, Shin was working alone at the bedside of a female patient who had suffered a hemorrhagic stroke. The condition led to bouts of agitation requiring restraints on her feet and wrists—not only to protect those attending her, but also to ensure she couldn’t pull out the wires and tubes that were keeping her alive.

The patient became suddenly fierce, twisting and breaking free of the restraints and delivering multiple blows to Shin’s face, chest and stomach. “If I’d been knocked out and unable to call for help, she could have killed me,” Shin says. It took four nurses and several other staff members to wrestle the patient into a chair, and she continued to spew threats until she was finally sedated.

“I was in shock, but the attitude around me was that this was all in a day’s work,” says Shin. She completed her shift that night, realizing how much pain she was in only after the adrenaline wore off. Bruised and sore, she called in sick the next two nights.

In health care settings around the country—especially in emergency rooms and psychiatric units—dealing with such attacks is increasingly common. Violence in hospitals, havens of care and compassion, is an underreported and sometimes daily threat to nurses, physicians and other providers, who risk both verbal and physical harm. Hospital employees are hurt by violence at more than four times the average rate for workers in all other private industries, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, and most hospital security directors polled for a survey by the International Association for Healthcare Security and Safety (IAHSS) and the American Society for Health Care Engineering (ASHE) said they had seen an increase in violence against their staffs during the most recent year.

Some incidents make headlines. In November a gunman at Mercy Hospital in Chicago killed a physician, a pharmacy resident and a police officer before shooting himself. A Long Island hospital patient kicked his physician unconscious, punched a security guard and set his bedsheets on fire; a patient in Cleveland pinned an emergency department nurse against the wall and sexually assaulted her; a disgruntled supply worker at an Alabama hospital fatally shot a nursing supervisor and wounded another employee before shooting himself; a prominent Houston cardiologist was killed by a man whose mother had died under the doctor’s care 20 years earlier.

Yet less newsworthy acts of violence are far more common. Caregivers routinely deal with patients who lash out by spitting, hitting, pulling hair, biting, choking or throwing things. There’s also verbal abuse, threats and harassment. In one recent survey, 71% of nurses and 47% of physicians said they had been harassed by patients through stalking, persistent attempts at communication and inappropriate social media contact, among other threatening actions.

“Violence occurs throughout the hospital,” says Judith Arnetz, a professor and associate chair for research in the Department of Family Medicine at Michigan State University in Grand Rapids, who studies the topic. Nurses, nursing aides and behavioral health staff members suffer the highest rates of abuse and violence, she says, and physicians, particularly in the emergency room, are also at high risk.

Hospitals and health care systems spent an estimated $1.1 billion on security and training to prevent violence in 2016, with an additional $429 million put toward medical care, staffing, compensation for lost wages and other costs related to violence against employees, according to a report by the American Hospital Association.

Amid a human and financial toll that is obvious and increasing, more and more academics, health care workers, medical and industry associations and hospital leaders are pushing for solutions. Some hospitals have begun to step up their efforts to curb workplace violence, while unions, regulators and lawmakers, among others, advocate sweeping reforms that could break the cycle of violence.

THE NUMBERS UNDERSCORE THAT this is a large and escalating problem. Three-quarters of the nearly 25,000 people reported assaulted at work each year have jobs in health care or social services, according to the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA), and a Government Accountability Office report in 2016 found that health care workers experience five to 12 times more violence than other workers do. Other studies have shown that few hospitals, clinics and nursing homes have avoided violent incidents.

One in four nurses has been physically assaulted on the job, and about half have been physically or verbally threatened, according to the American Nurses Association; roughly one-third of approximately 3,500 emergency room physicians polled recently said they had been physically assaulted by patients within the past year, and seven in 10 said violence had increased in the past five years. Asked about their experiences with patients in a single week, more than half of about 7,000 ER nurses said they had been abused verbally, and more than one in 10 reported physical violence. A 2016 The New England Journal of Medicine review of medical literature on workplace violence in health care summarized the problem as “underreported, ubiquitous and persistent”—and largely ignored.

Most violent incidents fly under the radar, says Gordon Lee Gillespie, a professor at the College of Nursing at the University of Cincinnati. A registered nurse who has worked in hospitals for more than 15 years, Gillespie has suffered two serious assaults and more than 100 cases of other physical and verbal abuse from patients. “I never thought much about it—it seemed a normal part of the day,” he says. When several nursing colleagues of his filed a lawsuit against a patient for assault, the judge threw out the case, saying that violence was just part of their line of work.

Multiple studies show that most health workers don’t report incidents because of time constraints, cumbersome reporting mechanisms and fear of reprisal. “Nurses tell me if they wrote up every event, they’d have no time to take care of patients,” Gillespie says. “There’s also the worry that reporting something will be held against you in your evaluation. And if you report a lot of it, the hospital is going to find a way to get rid of you—because you’ll be blamed for causing the problem.”

Many nurses also fail to report violence because they believe nothing will be done, according to a 2014 study, “Nothing Changes, Nobody Cares: Understanding the Experience of Emergency Nurses Physically or Verbally Assaulted While Providing Care,” published in the Journal of Emergency Nursing. Another study found that in most cases, nurses who did notify security personnel or a supervisor about attacks received no response from the hospital.

Yet a lack of reporting does nothing to diminish the impact of assaults on health care workers. Victims of this violence sometimes suffer symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder, according to several studies, and they may be prone to absenteeism and to patient safety errors and lower patient satisfaction. A survey of workplace violence by the Emergency Nurses Association found that one in four nurses considered going to a different ED or to a non-emergency department. Violent incidents also contribute to high burnout rates of ER physicians, says Paul Kivela, managing partner of Napa Valley Emergency Medical Group in California and president of the American College of Emergency Physicians. “Our job is stressful enough without the threat of being assaulted on a regular basis,” he says.

BUT WHY IS VIOLENCE in hospitals and other health care settings so frequent and persistent? In 2015 OSHA identified more than a dozen risk factors, including overcrowded waiting rooms, unrestricted public access and poor lighting in hallways and other areas. Violence in hospitals can also spill over from gang activity and other crime in surrounding communities. “What happens in health care settings is a reflection of what happens in society,” says IAHSS president-elect Alan Butler.

Several trends—federal spending cuts on mental health programs, the deinstitutionalization of patients with psychiatric problems and an epidemic of substance use disorders—have made hospital emergency rooms especially dangerous, says Terry Kowalenko, chair of emergency medicine for Beaumont Health System in Michigan and a researcher on ER violence. “ERs are more crowded, patients face long waits and there’s no question violence is a growing problem,” says Kowalenko. “Intoxicated patients and those with psychiatric illnesses are also more likely to perpetrate violence on staff.”

Patients in pain or cognitively impaired because of dementia, addiction or intoxication are likelier to lash out, according to research. And words can sometimes do as much damage as physical violence. An encounter with a patient who threatened Kowalenko late one night after he refused to write an opioid prescription remains seared in his memory. “‘Your shift is almost over and I’ll be waiting for you in the doctor’s parking lot,’ he told me,” says Kowalenko. “I found every reason to stay later than usual and I had security walk me out at 1 a.m. He wasn’t there, but of all the violent acts by patients that I’ve witnessed or been part of, that’s the one that affected me most.”

To help keep health workers safe, OSHA has long provided guidelines for preventing workplace violence, and in 2015, in response to rising rates of attacks, the agency updated its guidance for health care and social service workers. Yet even as violence has increased, just about three-fifths of hospitals have bumped up their security budgets, according to a recent survey. “There’s still a lack of understanding of security and safety by some hospital leaders; some budgets are increasing but there’s also immense pressure to contain costs,” says Tom Smith, president of Healthcare Security Consultants in Chapel Hill, N.C., who notes that although many hospitals are spending more on staff training, technology and other security measures, they may still resist hiring additional security personnel.

Still, there is a growing trend of arming existing security staff or having officers carry batons or pepper spray, despite questions about whether weapons deter violence. “Introducing weapons raises the risk of escalating violence because people tend to react to a weapon with a bigger weapon,” says Chris Van Gorder, president and CEO of hospital system Scripps Health in San Diego, who has worked as a police officer and a hospital security officer. “As an alternative to having our officers carry guns, we’re providing better training and giving them bulletproof vests and Tasers.”

Other hospitals are adding video surveillance of patients, visitors and staff and installing metal detectors and requiring identity badges or key cards for authorized personnel. They’re also improving lighting in parking lots, hospital corridors, stairwells and elevators, and providing panic buttons that staff members can use to call for help.

Because much of the violence involves fists and feet rather than guns or other weapons, training clinicians how to deter or respond to an attack can be crucial. In the recent IAHSS/ASHE survey of hospitals, most respondents had plans to train personnel to watch for early signs of agitation and aggression in patients by reading body language, facial expressions or behavioral cues such as pacing or rapid speech. Providers are also taught tactics for easing the tension and ways to protect themselves—for example, always having a quick exit route.

Since Massachusetts General Hospital began offering staff members access to training and videos that teach de-escalation techniques, violent incidents requiring physical restraint of patients or visitors have fallen by as much as 80%, says Bonnie Michelman, executive director of MGH’s Police, Security and Outside Services. Michelman also handles security planning and operations for Partners HealthCare, a system that includes MGH and nearly a dozen other hospitals. Although reporting rates have risen, the number of reported incidents overall hasn’t increased at the hospitals, she says, and fewer cases of verbal abuse now escalate to physical assault.

OSHA, the Joint Commission (an accrediting organization for hospitals) and other regulators are encouraging hospitals to create comprehensive workplace violence prevention plans, and in 2016 the AHA launched a campaign, Hospitals Against Violence, that grew out of an earlier meeting of the organization’s board of trustees, says Laura Castellanos, an AHA associate director. “There was a lot of emotion because of some recent mass shootings,” Castellanos says. As part of the campaign, case studies, fact sheets and webinars on education, training and workplace violence prevention are now available on the AHA website.

In a related effort, the first randomized, controlled, large-scale study of a standardized approach that hospitals might use to combat violence was published in the Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine in 2017. The project was designed to help develop a possible blueprint for future efforts, says Michigan State’s Judith Arnetz, who led the four-year effort involving 41 units of seven hospitals in the Detroit Medical Center. Twenty units functioned as controls, operating as usual, while teams at the 21 intervention units were encouraged to experiment with solutions. They were given three years of data on past violent events and injuries specific to their work areas and were asked to devise action plans. Those units implemented physical changes—bedside alarm buttons and better lighting in parking lots—as well as administrative changes, such as increasing staffing levels. They also taught providers how to deal with aggressive patients. The interventions significantly reduced the risk of violent events as well as the risk of violence-related injuries.

In its attempt to head off violence, the Veterans Health Administration, the largest health system in the country, has created pop-up alerts in the electronic records of certain patients. Before someone may be identified in this way, however, a multidisciplinary team at each facility conducts a rigorous review of the patient’s medical history and behavior, says Lynn M. Van Male, director of the VHA Workplace Violence Prevention Program. Caregivers are given a “safety action plan,” and some of these may contain restrictions—how and where health care can be delivered, for example. In the case of these retrictions, the patient is notified and offered the opportunity to appeal. Often patients are willing to meet with providers to discuss options, which may include different care management strategies. Some patients may interact with providers from home using tablet computers rather than coming into a facility in which they may get anxious and be more likely to act in unsafe ways, Van Male says.

Modeling its program on the VHA effort, the University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics created its own system that included health record-flagging five years ago, and in 80% of cases that were flagged, there have been no additional violent incidents, says Lance Clemsen, a social work specialist at UIHC and chair of the hospital system’s Disruptive Patient and Visitors Program. For the other 20% of cases there was a sharp decline in “code greens,” situations in which a security team gets involved. Overall, however, reported violent incidents in the hospital increased 25% in 2017 over 2016, says Doug Vance, director of the UIHC Department of Safety and Security, an uptick he believes is tied to the hospital being at high capacity all year.

WITH RELATIVELY FEW FEDERAL protections for health care workers against violence, several states are making efforts to address the problem. For example, legislators in Massachusetts are considering Elise’s Law, named for an emergency nurse who was stabbed and almost died on the job in 2017, which would set certain state standards around health care violence prevention. Seven other states now require hospitals to offer workplace violence prevention programs, while more than 30 states have made it a felony to assault health care workers or emergency medical personnel. And California legislation that took effect in 2017 requires the state’s health care employers to report and maintain records of workplace violence, information that will be published in January 2019, and to develop comprehensive prevention plans.

Last March, Ro Khanna, a Democrat from Silicon Valley, introduced national legislation in the U.S. House of Representatives modeled after the California law. The Health Care Workplace Violence Prevention Act defines wokplace violence as both acts and threats and requires all health care employers to adopt measures similar to the California regulations, emphasizing reporting, prevention, adequate staffing, training and worker participation.

The bill has attracted bipartisan support and more than two dozen co-sponsors. Still, Khanna acknowledges that the Trump administration’s anti-regulatory push is an obstacle. “These regulations will have to be well crafted,” he says. “But I don’t understand why anyone would oppose legislation to make the workplace safer for health care workers, particularly nurses.”

Others, however, question whether a national standard on staffing levels or violence prevention could work when there are such wide disparities in the kinds of hospitals and the patient populations they serve. “A one-size-fits-all approach ignores hospitals’ individual needs,” says Lawrence Hughes, assistant general counsel for the AHA. The hospital association would prefer to have OSHA conduct additional research into approaches that could be tailored to specific circumstances.

Looking back now, Allysha Shin emphasizes that her attack occurred even with preventive measures that were in place at Keck Medicine of USC. The health system provides de-escalation training for staff and has protocols for dealing with agitated patients that Shin followed. Moreover, a staff member who responds to the needs of difficult patients was working with Shin, but she had been called to another room before Shin was assaulted.

Shin, who did file a report with the hospital and continues to work at Keck, has testified before government agencies as an advocate for workplace violence prevention. “No one should have to go through what I experienced,” she says. “We’re at the point of: How many more nurses or health care workers have to die before this issue is front and center?”

Dossier

“Workplace Violence Against Health Care Workers in the United States,” by James P. Phillips, The New England Journal of Medicine, April 2016. An emergency medicine physician discusses violence in health care and the challenge of finding solutions.

“Preventing Workplace Violence: A Roadmap for Healthcare Facilities,” by the Occupational Safety and Health Administration, December 2015. This report outlines five core components of violence prevention programs and real world examples of how hospitals have implemented policies to protect staff.

“Preventing Patient-to-Worker Violence in Hospitals: Outcome of a Randomized Controlled Intervention,” by Judith Arnetz et al., Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, January 2017. This study examines data-driven interventions that showed significant differences in incident rates of violent events inflicted by patients.

Stay on the frontiers of medicine

Related Stories

- The Battle of the Bouffant

Guidelines for operating room attire may change in 2019 and ease tension over donning the controversial bouffant.

- Should Older Patients Have Their Own ED?

Advanced age brings special needs, especially in the emergency department. So some hospitals are changing designs and processes for their senior patients.

- The Shape of Things

Design choices pervade the health care system, and pediatrician Joyce Lee wants to make them smarter.