Published On June 13, 2017

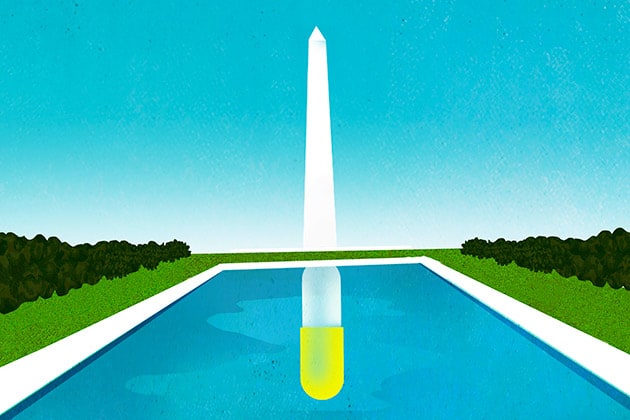

ON APRIL 25, 2016, a procession of doctors, researchers, parents and adolescent boys—many of the last group in wheelchairs—approached a microphone, one after the other, and asked a Food and Drug Administration advisory committee to recommend approval of an experimental drug called eteplirsen. It’s not unusual for several clinicians and patients to be invited to testify before these committees, which are made up of experts from outside the FDA. But interest in eteplirsen, which would be the first drug approved to treat Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD), was so great that the session had to be held in a hotel ballroom.

The medication targets a genetic mutation found in 13% of people who have DMD, a condition that primarily afflicts boys and leads to muscle deterioration. Most patients are unable to walk by age 12 and eventually develop severe heart and lung problems; few live past 30.

In front of hundreds of attendees, who often cheered and clapped, 50 people made the case for eteplirsen during the portion of the meeting set aside for public comment. One DMD patient, a teen named Billy Ellsworth, implored the panel, “FDA, please don’t let me die early.”

Despite the passionate testimony, the advisory committee voted seven to six against approving eteplirsen for sale—though this was only a recommendation they would make to physician Janet Woodcock, director of the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER). The committee members who opposed approval were unconvinced by the clinical data submitted by the drug’s maker, Sarepta Therapeutics, because the evidence came from a single small study that many experts considered problematic. Several months later, however, Woodcock rejected the committee’s advice and granted eteplirsen accelerated approval. In an extraordinary move, FDA scientists then asked the agency’s commissioner, Robert Califf, to overrule Woodcock’s decision. Califf declined their appeal but issued a 126-page critique of the approval, citing “major flaws” in the study it was based on. The drug moved to market, and eteplirsen is now sold under the brand name Exondys 51, with a price tag of $300,000 per year.

Some drug policy experts were convinced that Woodcock was swayed not by the scientific evidence but rather by the lobbying of patients, their families and DMD organizations. “Janet Woodcock basically caved,” says researcher Gregg Gonsalves, co-director of the Global Health Justice Partnership at Yale University, who closely followed the evaluation of eteplirsen. “Now we have a drug on the market that’s $300,000 per year, and we really don’t know whether it works.”

Gonsalves isn’t opposed to lobbying on behalf of patients. In the 1990s, he and other activists argued for speedier development and approval of drugs that would treat

HIV/AIDS, an advocacy that ultimately saved thousands of lives. Diana Zuckerman, an epidemiologist and president of the National Center for Health Research, a think tank focused on child and adult health, agrees that before the AIDS crisis, patients had little say or involvement in drug development and approval. But if AIDS activists wrote the playbook for how to lobby the FDA for better treatments, “the pendulum has swung too far,” says Zuckerman.

She and Gonsalves argue that pharmaceutical companies now sometimes use the emotional stories of patients and their families to persuade regulators to make hasty approvals of medicines that have doubtful value. Advocacy groups, for their part, deny being used as pawns of industry, arguing that input from people with diseases that lack effective therapies plays an increasingly crucial role in developing new medicines.

The FDA disputes the idea that patient advocacy was the deciding factor in the approval of eteplirsen, insisting in an email that Woodcock’s decision was based on science. But the agency does point with pride to several programs it has created that formally solicit the views of patients. In 2013, for example, the agency launched public forums at which people with various diseases and conditions described their daily lives and treatment priorities. And the 21st Century Cures Act, signed into law last December, allows the FDA to expand its use of “patient experience data” in evaluating the risks and benefits of new treatments.

Whereas the AIDS epidemic offers a clear example of how patient lobbying can lead to important advances, public pressure may have encouraged the FDA in other cases to approve medicines that don’t appear to do much. No one disputes that the stories of patients and their families hold enormous value. But can their desperate calls for action sometimes cloud the FDA’s judgment?

ON THE MORNING OF October 11, 1988, FDA employees watched from their windows as more than 1,000 AIDS activists marched on the agency’s headquarters in Rockville, Md. Protesters chanted slogans: “Hey, hey, FDA, how many people have you killed today?” A smoke bomb exploded, somebody broke a window, and by the end of the day police had made 185 arrests. Print and broadcast reporters were on hand, tipped off by the advocacy group ACT UP (AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power), which ensured that the protest made the evening news and morning papers.

The march on the FDA carried a clear message: We need treatments, now. The first AIDS cases had been identified seven years earlier, yet patients and their advocates saw the FDA as slow to act, blocking access to medicines that might save lives.

Despite signs that the U.S. government was ignoring the crisis—President Ronald Reagan didn’t mention AIDS publicly until 1986—the FDA had in fact begun to take action by the time of the 1988 protest. A year earlier, the agency had established a program to grant limited access to unapproved investigational drugs for people with serious or immediately life-threatening diseases for which there were no other treatment options. When early trials showed promise for the drug zidovudine, better known as AZT, more than 4,000 patients were able to start taking the medicine before it was granted approval in 1987. And after the protests—although declining to admit that it was responding to them—the agency established expanded access and accelerated approval programs.

Eventually, government regulators and at least some AIDS activists formed a kind of partnership. The FDA and the National Institutes of Health appointed members from the protest groups to committees that reviewed study designs and results, and helped decide which experimental drugs to test. Meanwhile, AIDS activists worked closely with pharmaceutical companies that were developing a new class of drugs called protease inhibitors. The first such drug was approved in 1995, and protease inhibitors were so effective that they helped transform AIDS from a fatal disease to a manageable chronic condition.

Yet Yale’s Gregg Gonsalves, who was in the thick of the patients’ push, is quick to note that most of the early AIDS drugs turned out to have little or no long-term benefit. With those disappointments in mind, Gonsalves and some others in the AIDS community preached caution when protease inhibitors came along, arguing for a slower approval process with time to test the drugs. That infuriated many AIDS activists and patients who wanted the drugs as soon as possible.

Quick approval won out, with the FDA giving the nod to the first protease inhibitor, saquinavir (Invirase), in just 97 days. “We got lucky,” says Gonsalves, noting that even though its safety remained an open question at the time it was approved, the drug ultimately became a game changer in the fight against AIDS.

While protease inhibitors were a success, their rushed timetable had an unintended consequence, Gonsalves says. Drug companies embraced the power of the patient, enlisting and sometimes creating advocacy groups to lobby regulators for faster access. “You now have parents screaming bloody murder that their kids need these drugs,” says Gonsalves. “We opened Pandora’s box.”

Gonsalves and others point to the FDA’s 2015 approval of flibanserin (Addyi), a drug for low sexual desire in females sometimes called “pink Viagra.” Valeant Pharmaceuticals, which acquired the drug in 2015, notes that the FDA based its approval of flibanserin on three controlled clinical trials that “demonstrated a significant increase in the number of sexually satisfying events” in women who used the drug. But the FDA initially rejected flibanserin twice on grounds that its modest benefits didn’t outweigh potential risks; studies suggested that women treated with the drug experienced 0.5 additional such encounters per month while risking dangerously low blood pressure.

Sprout Pharmaceutical purchased the rights to flibanserin in 2010 and launched a nationwide campaign. TV commercials spoofed ads for erectile dysfunction drugs and blamed sexism for the lack of treatments available to women with low sexual desire. Diana Zuckerman’s staff from the National Center for Health Research attended the advisory committee meeting at which Sprout once again made the case for FDA approval. Her staff reported that “there were dozens of crying women saying, ‘I desperately need this,’” she recalls, with some describing how low sexual desire had harmed their marriages. The committee voted 18 to 6 in favor of approval.

Months later, a committee member who voted for approval conceded to Zuckerman that Sprout’s data was unimpressive but that flibanserin seemed safe—and that the tears of women who testified left an impression on him. “Seeing these women cry made him realize how serious this problem was,” says Zuckerman. Relatively few women have since sought Addyi prescriptions.

THE FDA STATED THAT science guided their eteplirsen decision, not the forces of patient advocacy. But the methodology of that science has come under scrutiny. “Everything about this approval was highly unusual,” says internist Joseph Ross of Yale University, who analyzes efficacy trials that the FDA uses to decide whether to approve a new drug.

Start with the size of the study. Ross’ research indicates that a typical “pivotal trial” on which the FDA bases its drug approval decisions includes an average of 760 patients. That threshold is naturally lower for rare diseases such as DMD, which has an estimated 2,000 to 2,500 cases in the United States. Earlier in 2016, the FDA declined to approve a related DMD drug called drisapersen, which had been tested on only 290 patients. The study Sarepta submitted for eteplirsen included just a dozen boys.

Even more controversial was the measurement of dystrophin. The FDA’s approval of eteplirsen was based on the drug’s ability to increase dystrophin in muscle, which is absent in DMD patients. The trial of 12 boys presented to the FDA showed such an increase, and neurologist Jerry Mendell and colleagues at Nationwide Children’s Hospital in Columbus, Ohio, used several different techniques to measure it. One method, Western blot analysis, found that eteplirsen increased overall dystrophin levels, but only to about 1% of the level occurring in healthy muscle. “The very slight increases in dystrophin production didn’t seem to me reasonably likely to predict the possibility of clinical benefit,” says internist Aaron Kesselheim of Boston’s Brigham and Women’s Hospital, who was one of the FDA advisory committee members who voted against recommending approval of eteplirsen.

Mendell argues that the other measurement method he used, immunohistochemistry (IHC), which detects the total number of muscle fibers that have at least some dystrophin, is more reliable. In his 2013 trial, Mendell found that eteplirsen increased dystrophin-positive fibers by almost 33%—news that thrilled the DMD community. The FDA insisted, however, on conducting an independent reanalysis of the biopsies, which found a much lower percent increase.

Mendell counters that the FDA used more conservative criteria to count fibers with dystrophin. His own reading of the reanalyzed IHC data performed by the FDA indicates that eteplirsen increases dystrophin-positive fibers by 16%, on average. Such an increase is enough to slow the progression of DMD, he says, adding that his investigation suggests that’s what has happened. While two of the 12 boys in his trial required wheelchairs soon after the study began, Mendell notes that others continued walking for a longer duration and saw less of a decline in their ability to walk than would be expected for patients their age. In a letter to the eteplirsen advisory committee, 36 clinicians and researchers who treat and study DMD wrote that they believed the drug was likely responsible for the apparent slowing of the progression of DMD that Mendell had detected.

But while eteplirsen has a core group of believers, its long-term future in treating DMD is uncertain. As a condition of granting Sarepta accelerated approval to market eteplirsen, the FDA required the drugmaker to conduct a well-controlled study of patients to demonstrate that the medicine improves muscle function.

Some parents of boys taking the drug are convinced that it works. Josh Argall’s son, Devin, has been taking eteplirsen for more than two years as part of a separate study from Sarepta. “I thought by the time Devin was 12 or 13, he’d be in a wheelchair,” says Argall, of Manitowoc, Wis. But Devin, now 15, is still on his feet. “Devin walks a little faster than me, and he walks for miles,” says Argall, who believes eteplirsen is the reason his son can still get around. “The time this drug has given us is priceless,” he says.

Some programs are now exploring other places in the drug pipeline for input from patients, family members and other advocates. This would allow them to play crucial roles that go beyond weighing in on the often confusing scientific merits of new drugs. Some patient advocacy groups say that, beyond the financial support they provide for research, one of their most valuable contributions is offering patients’ perspectives to the FDA and drug developers.

Margaret Anderson, executive director of FasterCures, in Washington, D.C., talks about an emerging “science of patient input.” Her organization studies the methods that corporate and nonprofit organizations use to learn about patients’ experiences and priorities, and wants to create tools that can turn that information into hard data for drug developers. “We’re learning how we can get insights from patients earlier in the development process,” says Anderson, who believes that speeding up that flow of information could lead to more effective medicines.

One pioneer in the science of patient input, Parent Project Muscular Dystrophy (PPMD), is working with researchers at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. PPMD surveyed 119 parents and other caregivers of DMD patients about their treatment priorities: What benefits in a new drug for DMD would you prize most? What risks are you willing to tolerate? In a 2014 study published in Clinical Therapeutics, the team from PPMD and Johns Hopkins reported that most respondents said they would accept some risk of serious side effects in exchange for delaying muscle deterioration in the boys they care for. “Caregivers prioritized the slowing of the progression of the disease above extending life expectancy,” says Annie Kennedy, PPMD senior vice president of legislation and public policy.

PPMD has relayed this and other research about DMD patient and caregiver preferences and priorities to the FDA, hoping to help the agency evaluate new drugs and advise the pharmaceutical industry on how to design medicines and clinical trials. As other groups follow its lead, perhaps there will be better data to help regulators judge between the medicines patients say they want and those that can truly help them.

Dossier

“Clinical Trial Evidence Supporting FDA Approval of Novel Therapeutic Agents, 2005-2012,” by Nicholas S. Downing et al., JAMA, January 2014. This investigation looks at how the quality of clinical trial evidence considered by the FDA has varied greatly in recent years.

“Scientific Dispute Regarding Accelerated Approval of Sarepta Therapeutic’s Eteplirsen,” by Robert M. Califf, Department of Health and Human Services, 2016. This document describes the internal debate over eteplirsen within the FDA.

How to Survive a Plague: The Inside Story of How Citizens and Science Tamed AIDS, by David France (Alfred A. Knopf, 2016). A sprawling history of the AIDS epidemic is told by people who wrote the playbook on patient activism.

Stay on the frontiers of medicine

Related Stories

- The Right to Try

Five state legislatures now allow terminal patients to circumvent the FDA. Will this new path to experimental drugs help or hurt?

- Should Congress Pass the Cures Act?

Two experts face off on new legislation that aims to speed up the approval process for drugs and medical devices.

- Taking It to the Streets

Doctors have a long history as fighters for social causes. What can be done to make sure that legacy isn’t lost?